Quality Improvement/Patient Safety 1

Session: Quality Improvement/Patient Safety 1

010 - Improving Pediatric Lead Screening and Prevention in Primary Healthcare Setting: A Quality Improvement Initiative

Friday, April 25, 2025

5:30pm - 7:45pm HST

Publication Number: 10.5126

Diana Carolina Largo Luna, The Unterberg Children's Hospital at Monmouth Medical Center, Long Branch, NJ, United States; Kristin Pyne, The Children's Hospital at Monmouth Medical Center, Fair Haven, NJ, United States; Jacqueline G. Brunetto, Monmouth medical center RWJBH, Long Branch, NJ, United States

Diana Carolina Largo Luna, MD (she/her/hers)

Pediatric Resident

The Unterberg Children's Hospital at Monmouth Medical Center

Long Branch, New Jersey, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Childhood lead exposure remains a public health issue, with risks from sources like paint chips, old pipes, imported toys, spices, folk remedies and caregiver’s occupational exposure. Exposure to lead can negatively impact the cognitive function, behavior, and academic performance. Reduced cognitive function has been reported with lead levels as low as 5 mcg/dL.

Consequently, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends lead screening for all children at 12 and 24 months and targeted screenings for children up to 72 months. Despite these recommendations, many patients in our resident continuity clinic at the Monmouth Family Health Center did not have documented lead screening.

Objective: Improve detection and interventions of elevated blood lead levels (BLLs) for children aged 6 to 72 months by increasing a 10% over baseline in the following:

1. Lead screening at ages 12- and 24-months

2. Lead risk assessments at ages 6-72 months

3. Lead screening at 15, 18, 30, 36, 48, and 60-months patients with no prior screening

4. Follow-up of elevated BLLs

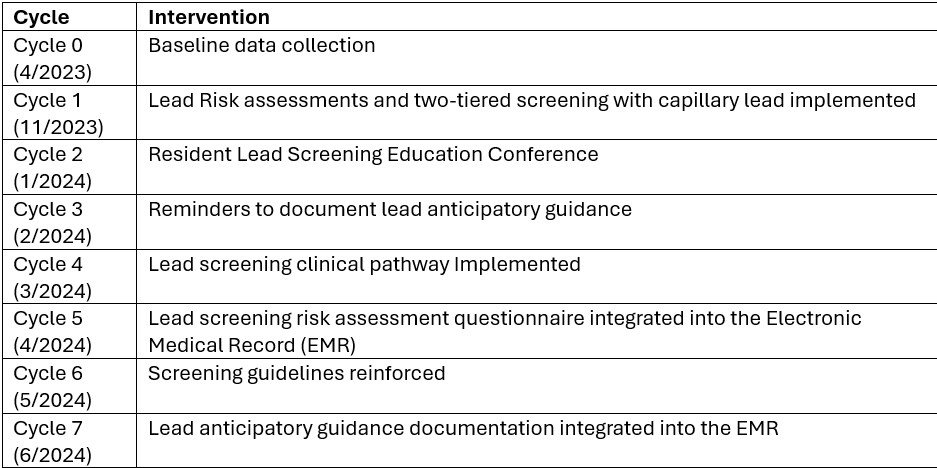

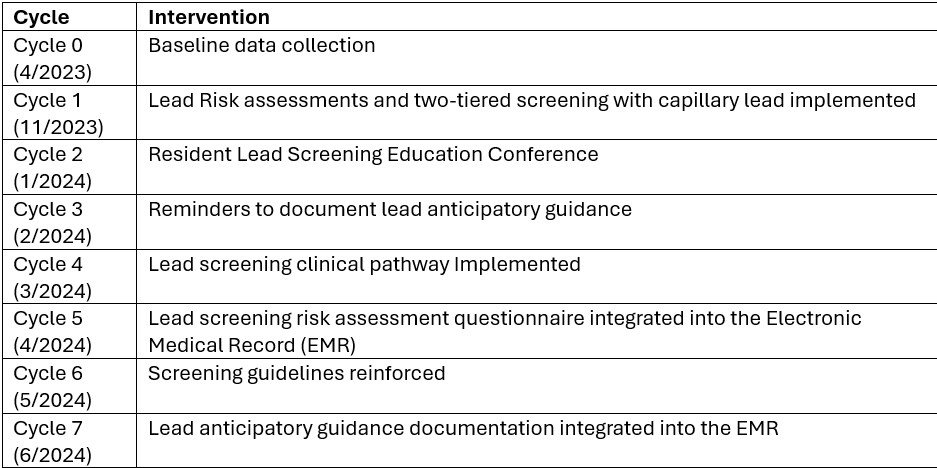

Design/Methods: Baseline data on lead screening and risk assessments was collected through chart review. Quality improvement methods were implemented to enhance lead screening through seven monthly Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles (table 1).

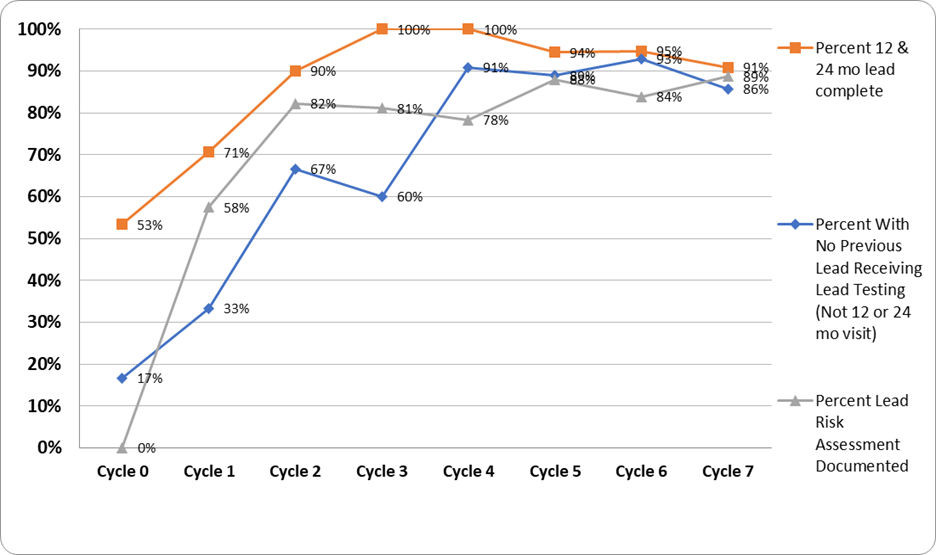

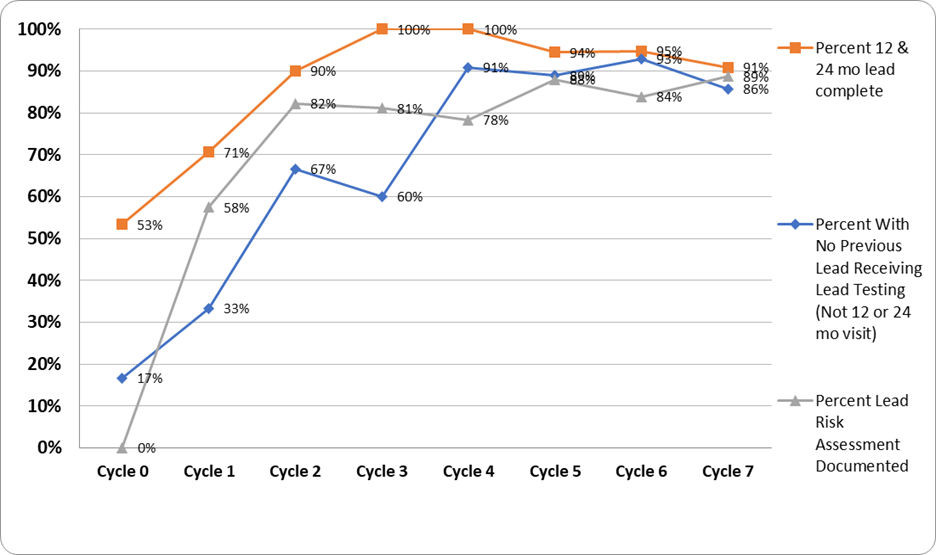

Results: By the end of cycle 7, all objectives showed significant improvements of over 10% from baseline (figure 1).

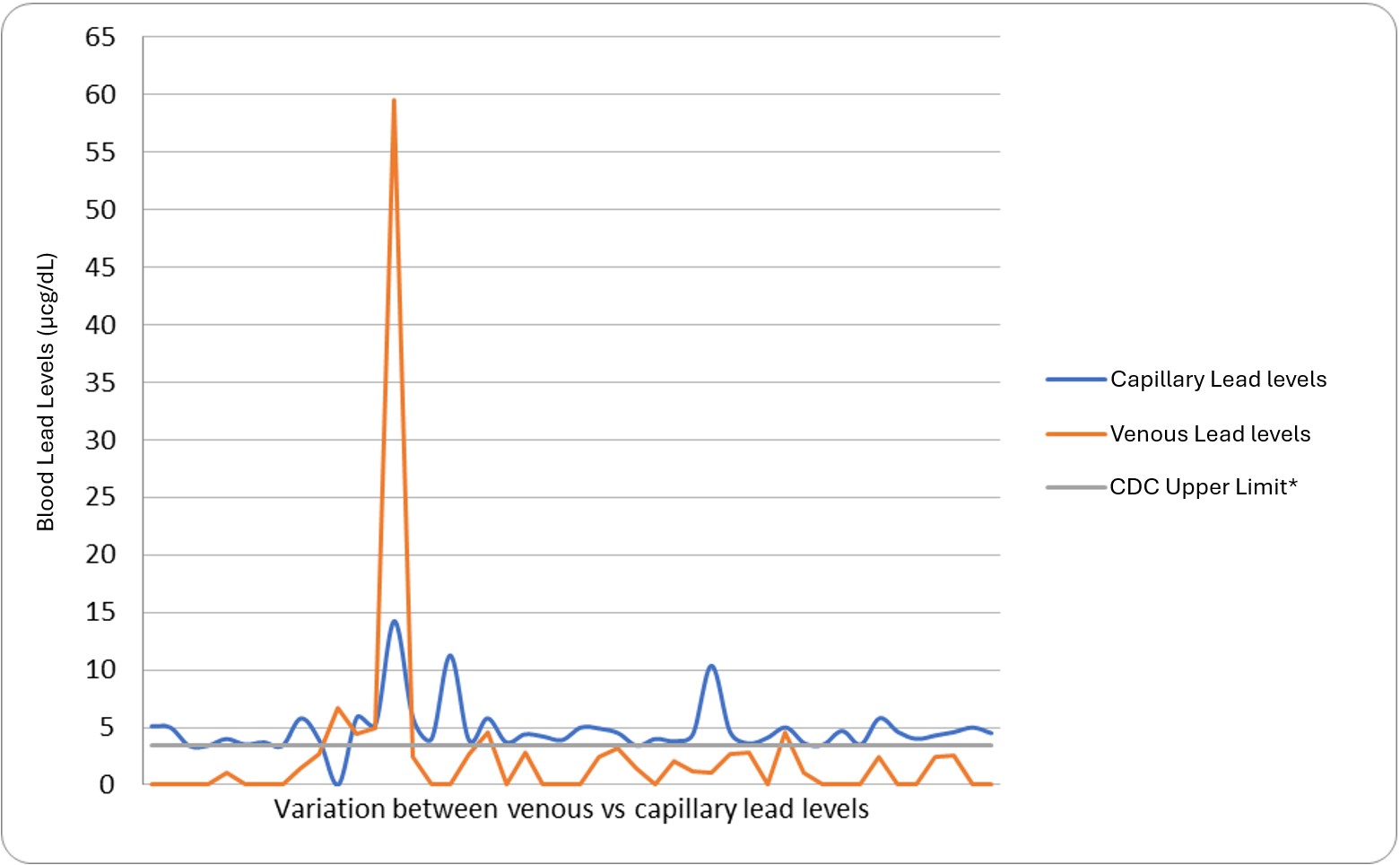

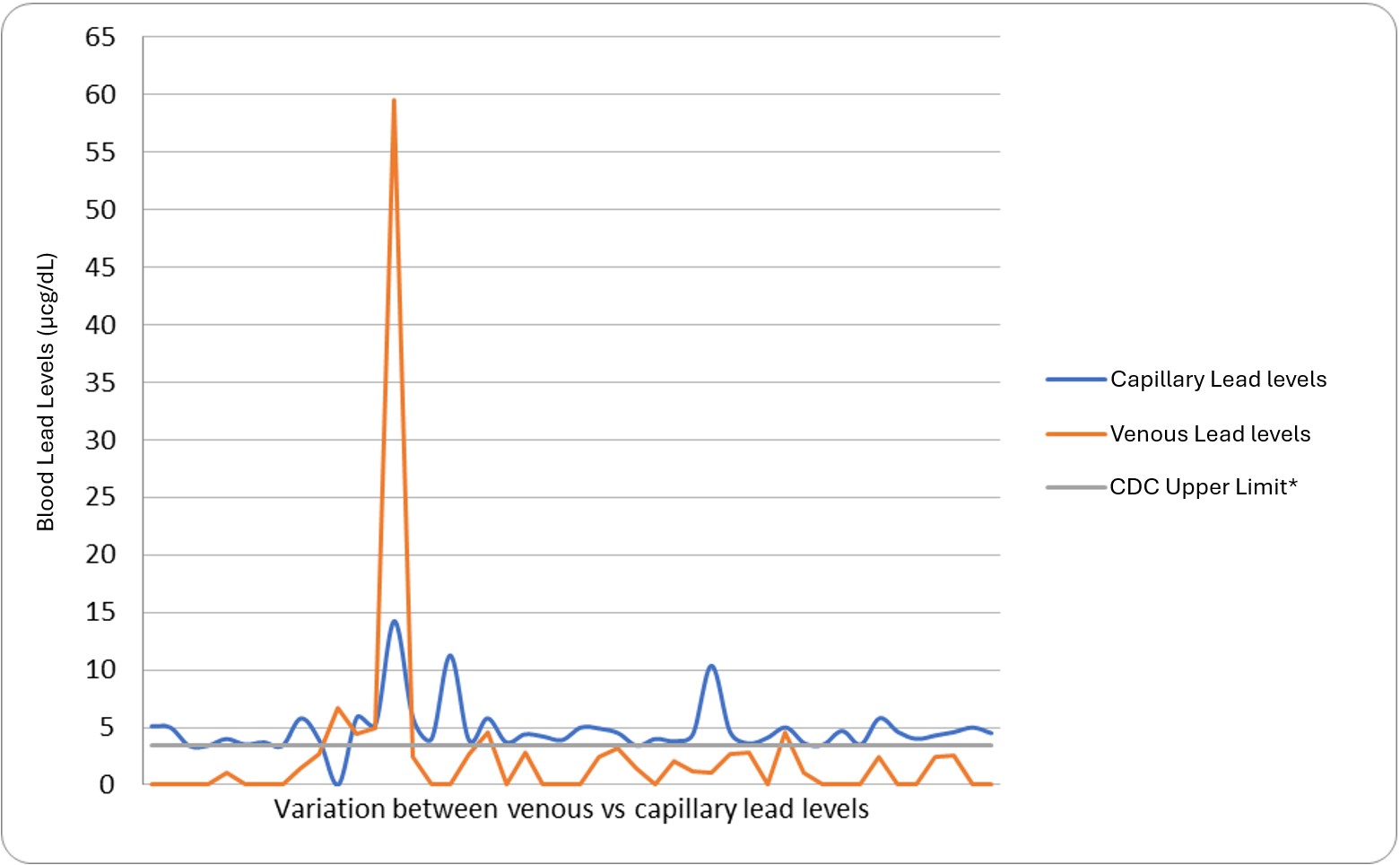

Across all cycles, 46 patients were identified with elevated capillary BLLs. Four did not receive confirmatory venous lead levels; two of these had normal repeated capillary lead levels and two never received a follow-up BLL. On venous testing, five patients had BLLs above the threshold of 3.5. Of these, three had BLLs less than 5 and required follow-up BLLs; one had a BLL of 59.5 and required chelation; and one had a BLL of 6.6, prompting home inspection (figure 2).

Conclusion(s): Practical and easy-to-implement changes in daily practices can help clinicians identify high-risk patients and increase adherence to AAP recommendations to reduce lead exposure in children. Our quality improvement project found that a risk assessment questionnaire helps identify potential exposure. Reinforcing AAP guidelines, along with point-of-care lead testing, increased screening rates. Most elevated capillary levels were falsely elevated and resulted in < 3.5 on a confirmatory venous sample. The two-tiered testing did result in more patients being screened compared to baseline, however, a larger sample size and more baseline data are needed to determine if this resulted in more patients with elevated venous BLLs being found.

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles

Lead risk assessment and screening compliance

Variation between Venous lead levels vs. Capillary lead levels

CDC (Center for Disease Control and Prevention), *CDC Upper Limit: 3.5 micrograms per deciliter.

CDC (Center for Disease Control and Prevention), *CDC Upper Limit: 3.5 micrograms per deciliter.Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles

Lead risk assessment and screening compliance

Variation between Venous lead levels vs. Capillary lead levels

CDC (Center for Disease Control and Prevention), *CDC Upper Limit: 3.5 micrograms per deciliter.

CDC (Center for Disease Control and Prevention), *CDC Upper Limit: 3.5 micrograms per deciliter.