Genomics/Epigenomics 1

Session: Genomics/Epigenomics 1

380 - Implementation of First-tier Rapid Genome Sequencing in Pediatric Wards

Friday, April 25, 2025

5:30pm - 7:45pm HST

Publication Number: 380.5412

Alexandra C. Keefe, Seattle Children's, Seattle, WA, United States; Abbey A. Scott, Seattle Children's, Seattle, WA, United States; Lukas Kruidenier, Seattle Children's, Seattle, WA, United States; Darci L. Sternen, Seattle Children's Hospital and PLUGS, Seattle, WA, United States; Sarah Clowes Candadai, Seattle Children's Hospital/PLUGS, Seattle, WA, United States; Shannon M. Stasi, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA, United States; Julia Parish-Morris, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, FORT WASHINGTON, PA, United States; Megan Sikes, Seattle Children's, Lake Forest Park, WA, United States; Margaret AAEA. Adam, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, United States; Anita E. Beck, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, United States; Jennifer C. Hayek, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, United States; Ian A. Glass, Univ of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States; James T. Bennett, Sea, Seattle, WA, United States; Ghayda Mirzaa, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, United States; Paul Kruszka, GeneDx, Alexandria, VA, United States; Kirsty McWalter, GeneDx, Gaithersburg, MD, United States; Bethany Friedman, GeneDx, Gaithersburg, MD, United States; Michael Bamshad, university of washington, seattle, WA, United States; Katrina Dipple, Seattle Children's, Seattle, WA, United States; Tara L. Wenger, Seattle Children's Hospital, Lake Tapps, WA, United States

Alexandra C. Keefe, MD, PHD (she/her/hers)

Assistant Professor

Seattle Children's Hospital / University of Washington

Seattle, Washington, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Data from over 3,500 critically ill children have demonstrated that first-tier rapid exome sequencing or rapid whole genome sequencing (rES/rWGS) results in improved access to a precise genetic diagnosis (PrGD), and reduced cost for critically ill infants and children with a suspected genetic condition. In contrast, there is relatively little published about the use of rES/rWGS in hospitalized children who are not critically ill, with fewer than 100 children reported collectively.

In May 2022, a large quaternary children’s hospital inpatient testing policy was amended to allow use of rES/rWGS as a first-tier test for all inpatients who received a genetics consult, including inpatients on general pediatric non-ICU wards. This policy change was motivated by results of SeqFirst-neo, a project that demonstrated a nearly 8-fold increase in access to a PrGD in critically ill neonates in the neonatal intensive care unit when exclusion-based criteria was used to identify children for rWGS. Based on the success of SeqFirst-neo, the hospital inpatient testing policy was changed in May 2022, allowing for first-tier rES in inpatients who received genetics consultation in whom a different testing modality was determined not to be superior (e.g. tissue-based panel testing for suspected mosaic disorders) following pretest counseling by a genetic counselor. The policy was later updated to replace rES with rWGS in May 2023.

Objective: The purpose of this current study was to determine the impact of this policy change on the rate of and time to PrGD for hospitalized children in non-ICU settings at a large quaternary children’s hospital.

Design/Methods: Retrospective chart review for non-critically ill inpatients who received genetics consults pre-policy change (January 2021-May 2022; n=55) and post-policy change (May 2022-June 2024; n=163).

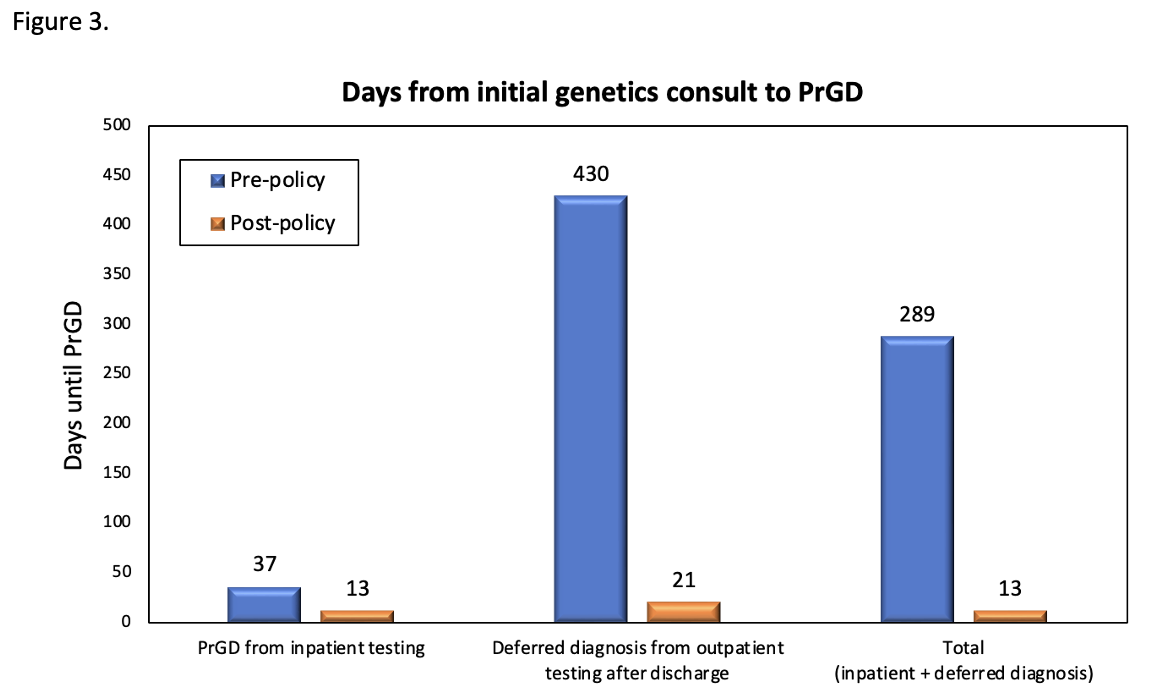

Results: rES/rWGS was ordered in 8/55 (14.5%) of genetics consultations from January 2021-May 2022, compared to 130/163 (79.8%) after the policy change. Average time to precise genetic diagnosis after genetics consult fell from 289 days before the policy change to 13 days after. Among inpatients who had rES/rWGS as an initial genetic test, 55/130 (42.3%) received a precise genetic diagnosis.

Conclusion(s): Rapid exome sequencing or rapid whole genome sequencing as first-tier testing resulted in a precise genetic diagnosis in 42.3% of non-critically ill pediatric inpatients, which is comparable to critically ill neonates, and substantially reduced time to diagnosis.

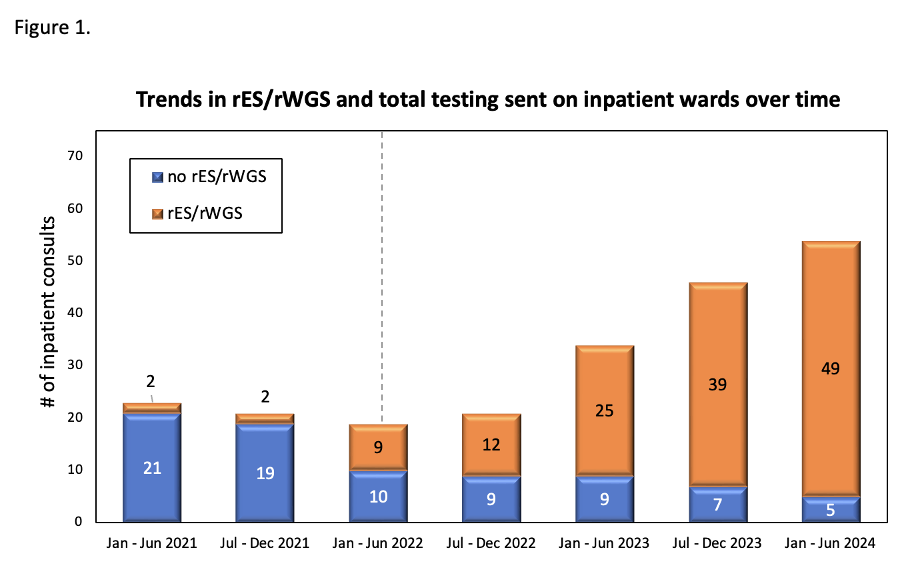

Figure 1. Trends in rES/rWGS and total testing sent on inpatient wards over time

Clinical ordering patterns for genetics consults from January 2021-June 2024 as assessed in 6 month intervals. Over the study period there was a steady increase in the number of consults requested and also in the percentage of consults in which rES/rWGS was recommended and ordered by the inpatient genetics consultation service. Dashed line denotes date policy change on May 4, 2022 allowing first tier rES/rWGS for inpatients.

Clinical ordering patterns for genetics consults from January 2021-June 2024 as assessed in 6 month intervals. Over the study period there was a steady increase in the number of consults requested and also in the percentage of consults in which rES/rWGS was recommended and ordered by the inpatient genetics consultation service. Dashed line denotes date policy change on May 4, 2022 allowing first tier rES/rWGS for inpatients.Figure 2. Flow diagram of genetic testing patterns and outcomes of testing.

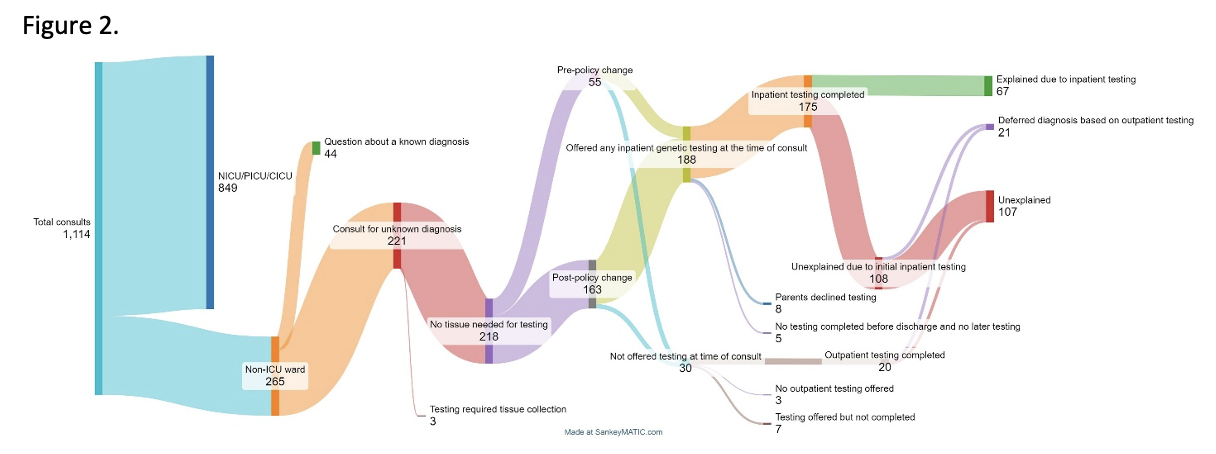

Patients who received genetics consultation from January 1, 2021 through June 30, 2024 included in the present study, testing patterns and outcomes of testing.

Patients who received genetics consultation from January 1, 2021 through June 30, 2024 included in the present study, testing patterns and outcomes of testing.Figure 3. Days from initial genetics consult to precise genetic diagnosis

Time to precise genetic diagnosis (PrGD) pre- and post-policy change. Comparisons between time to PrGD from testing sent from the inpatient setting at the time of initial consult, PrGD resulting from testing deferred to the outpatient setting after discharge, and overall time to PrGD for all patients who received inpatient genetics consultation between January 1st, 2021 and June 30, 2024.

Time to precise genetic diagnosis (PrGD) pre- and post-policy change. Comparisons between time to PrGD from testing sent from the inpatient setting at the time of initial consult, PrGD resulting from testing deferred to the outpatient setting after discharge, and overall time to PrGD for all patients who received inpatient genetics consultation between January 1st, 2021 and June 30, 2024.