Pulmonology

Session: Pulmonology

097 - Clinical phenotypes after discharge from the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) among preterm infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD)

Friday, April 25, 2025

5:30pm - 7:45pm HST

Publication Number: 97.4402

Timothy Nelin, Childrens Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, United States; Nicolas P. Goldstein Novick, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Rose Valley, PA, United States; Jonathan J. Szeto, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States; Matthew Kielt, Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH, United States; Leif D. Nelin, Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH, United States

Timothy Nelin, MD (he/him/his)

Attending Physician

Childrens Hospital of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: BPD is the most common morbidity following preterm birth and has been associated with increased risk of childhood asthma. Post-discharge respiratory phenotypes of infants with BPD and risk factors for asthma diagnosis in this high-risk population are not fully understood.

Objective: To describe post-discharge respiratory phenotypes of infants with BPD in relation to risk for asthma diagnosis.

Design/Methods: We conducted a retrospective cohort study of children diagnosed with BPD using the 2019 NRN criteria, born 2010-2019, discharged from a single hospital system to a home address in the Philadelphia metro area, with documented follow-up in the same hospital network. We reviewed patient charts for a diagnosis of asthma by age 5, identified by ICD-9/10 code. We assigned four respiratory phenotypes: (1) no asthma diagnosis, no inhaled respiratory medication use at NICU discharge; (2) asthma diagnosis, no medication use; (3) no asthma diagnosis, medication use; (4) asthma diagnosis, medication use. We compared characteristics amongst the phenotypes; performed multinomial logistic regression to characterize associations of respiratory phenotype with emergency department (ED) and inpatient admission in the year after NICU discharge, adjusting for relevant clinical factors and demographics; and carried out a sub-analysis limited to patients discharged with respiratory medications with logistic regression.

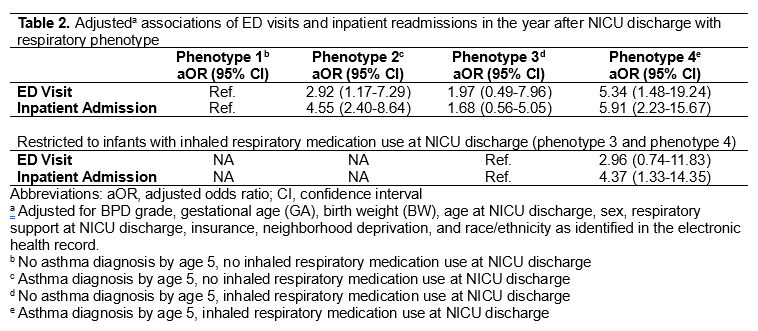

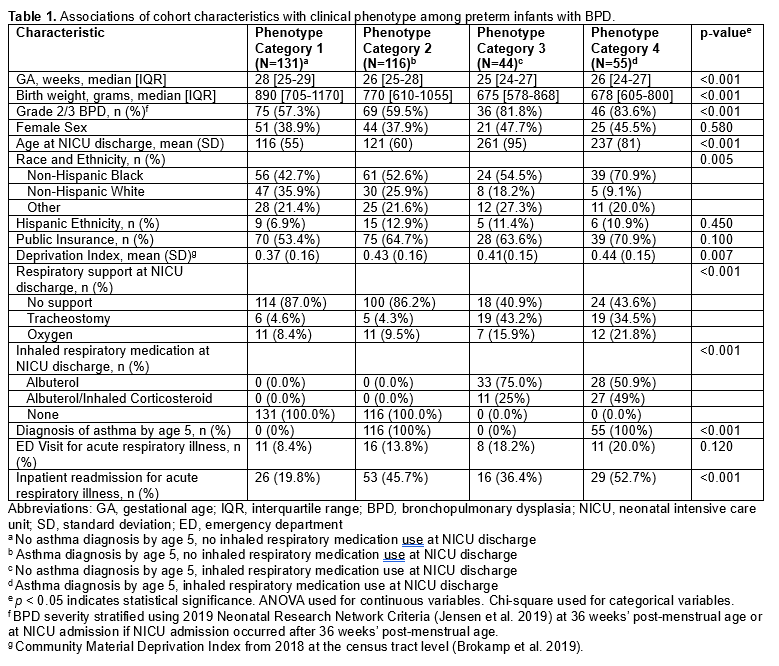

Results: Table 1 displays cohort characteristics. Compared to infants with phenotype 2, infants with phenotype 3 had lower GA (25 vs 26 weeks, p< 0.001) and BW (675 vs 770 g, p< 0.001) and more severe BPD (82% vs 60%, p< 0.001). Infants with Phenotype 4 had the lowest GA and BW and were more likely to be non-Hispanic Black, have higher neighborhood deprivation, be publicly insured, and have an inpatient admission. Compared to phenotype 1, inpatient admission in the year after NICU discharge was significantly associated with phenotype 2 (aOR 4.55, 95%CI: 2.39-8.64) and 4 (aOR 5.91, 95%CI: 2.23-15.67) (Table 2). Among infants discharged with an inhaled respiratory medication (phenotypes 3/4), inpatient admission was associated with increased risk of asthma diagnosis (aOR 4.37, 95% CI: 1.33-14.35).

Conclusion(s): Among children with BPD, the diagnosis of asthma is significantly associated with inpatient admission in the year after NICU discharge. Given the mounting evidence that patients with severe BPD may continue with symptoms and pulmonary function abnormalities into young adulthood, we postulate that the diagnosis of asthma may be a surrogate marker of on-going symptomatic severe BPD in these patients.

Table 1. Associations of cohort characteristics with clinical phenotype among preterm infants with BPD.

Table 2. Adjusted associations of ED visits and inpatient readmissions in the year after NICU discharge with respiratory phenotype