Global Neonatal & Children's Health 1

Session: Global Neonatal & Children's Health 1

726 - Developing a Pediatric Emergency Medicine Simulation-Based Learning Curriculum in Nepal

Friday, April 25, 2025

5:30pm - 7:45pm HST

Publication Number: 726.4189

Samantha M. Langer, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, United States; Christine Saracino, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, United States; Christopher Strother, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, River Vale, NJ, United States; Jared M. Kutzin, Icahn school of medicine at Mount Sinai, Ny, NY, United States; Roshana Shrestha, Kathmandu university school of medical sciences-Dhulikhel Hospital, Dhulikhel, Bagmati, Nepal; Darlene R. House, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, NEW YORK, NY, United States; Morgan Bowling, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New york, NY, United States

Samantha M. Langer, MD, FAAP (she/her/hers)

Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellow

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

New York, New York, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Dhulikhel Hospital (DH) is a teaching hospital in Nepal which treats over 200 children per month in their Emergency Department (ED). With a 90% admission rate, DH experiences a higher acuity than EDs in the U.S. Despite this, Pediatric Emergency Medicine (PEM) remains underdeveloped in low-resource countries (LRCs), such as Nepal. Low-fidelity simulation is an effective educational tool to improve providers' comfort with procedures and skills specific to the care of critically ill children.

Objective: This pilot project developed and delivered a reproducible and locally sustainable simulation-based learning (SBL) curriculum to enhance the confidence of DH medical providers in managing pediatric emergencies using simulation equipment procured with grant funding and donated to DH.

Design/Methods: This was a survey-based study of medical professionals at DH. Following a local needs assessment, four scenarios were selected: respiratory distress, status epilepticus, precipitous preterm delivery, and organophosphate poisoning. Participants completed anonymous pre- and post-simulation surveys regarding their comfort level with performing specific procedures and managing scenarios. Standardized pre-briefing and debriefing discussions were held. Key procedures were practiced after the simulations in hands-on skills stations.

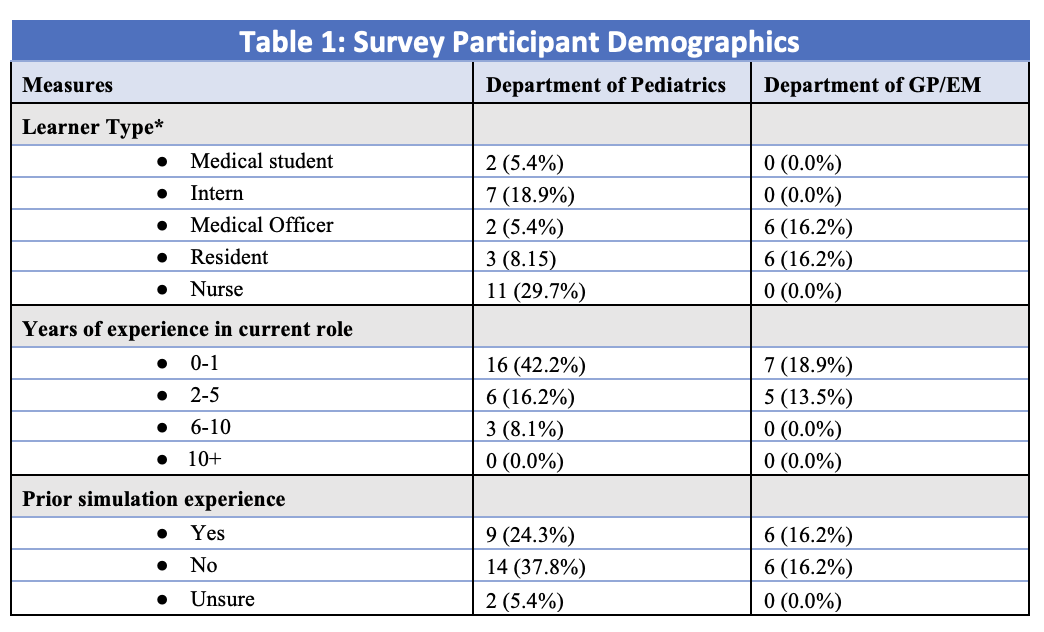

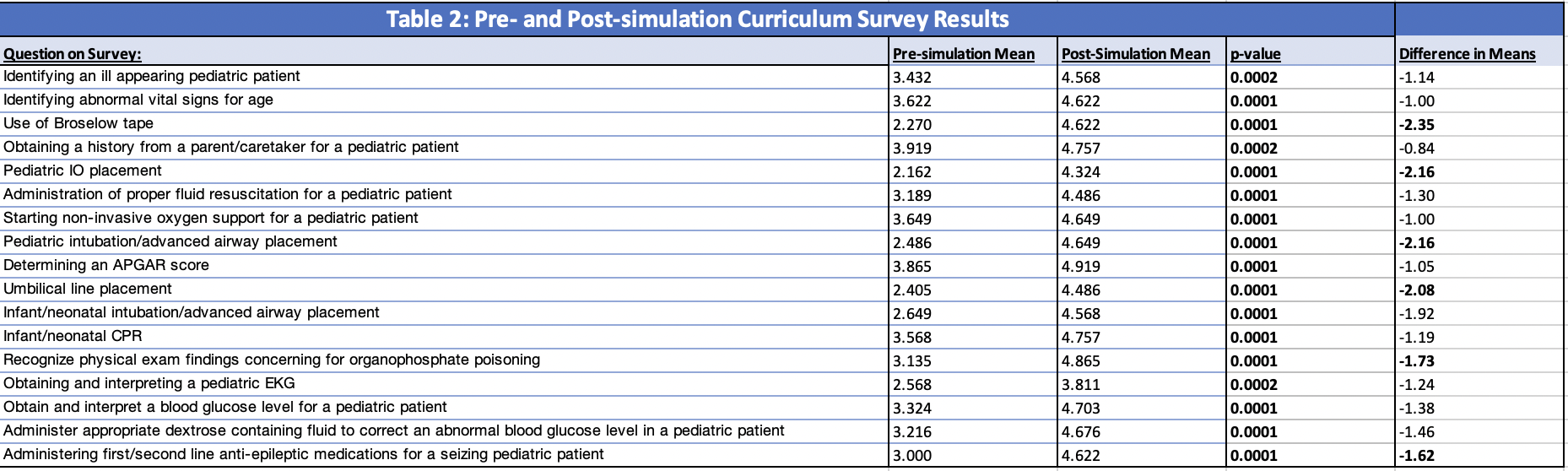

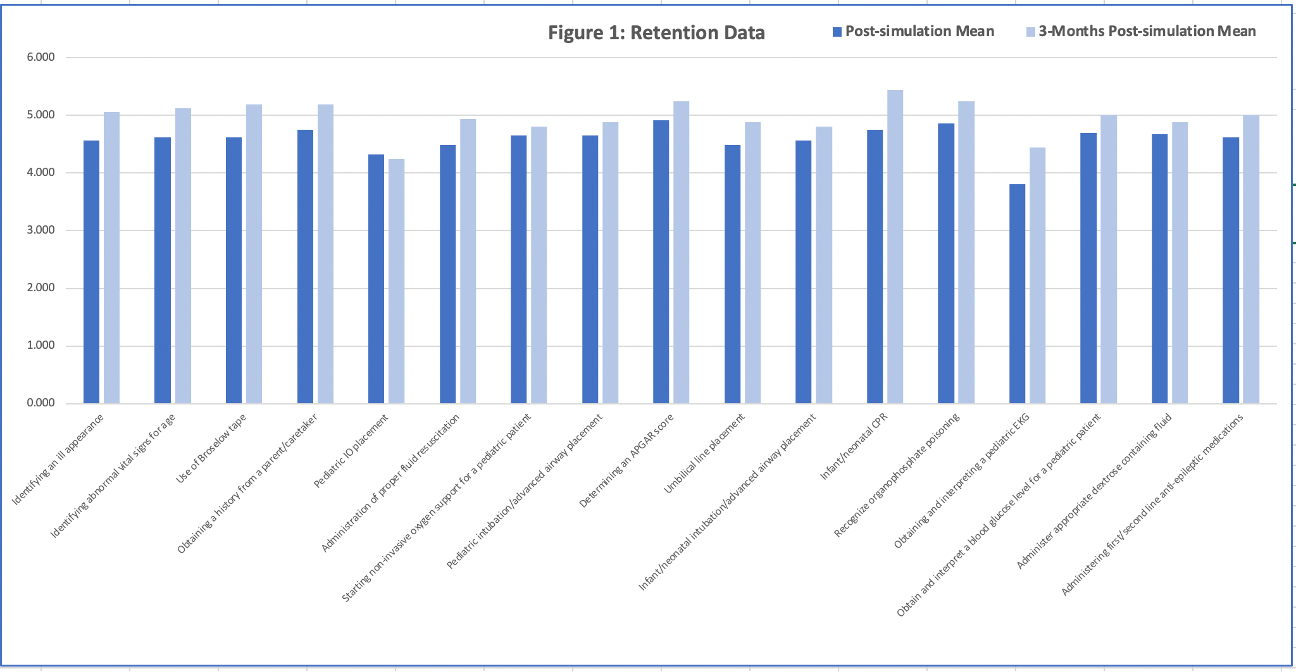

Results: The study sample included 37 participants. 54% (n=20) had never participated in simulation before (Table 1). Results of a paired, t-test analysis of the pre- and post-simulation surveys were reported with corresponding p-values at 95% confidence intervals (Table 2). All questions showed a statistically significant difference in provider comfort. A 3-month post-course survey was sent to assess retention and demonstrated overall consistency with comfort levels (Figure 1).

Conclusion(s): The data reflects that provider comfort increases after the implementation of low-fidelity SBL, with an emphasis on specific procedure training. There was a smaller difference in tasks in which providers were already familiar, such as obtaining a history. The questions with the greatest difference in provider comfort directly correspond to topics involving a skills station. Integrating simulation into medical education is strongly supported in the literature. Simulation is effective and should be implemented in LRCs, specifically with high acuity but lower occurrence skills, like intraosseous (IO) and umbilical line placement. As specialized PEM training expands, dedicated pediatric SBL can improve provider comfort with fundamental procedures to improve the outcomes of pediatric patients.

Table 1: Survey Participant Demographics

*The medical education process in Nepal differs from that in the US. Medical school is 5 years, followed by a 1-year internship. After passing a general licensing exam, they become a Medical Officer for 1-2 years, followed by an additional board exam. After passing the board exam, they can then apply to and complete a specialty specific 3- year residency program.

*The medical education process in Nepal differs from that in the US. Medical school is 5 years, followed by a 1-year internship. After passing a general licensing exam, they become a Medical Officer for 1-2 years, followed by an additional board exam. After passing the board exam, they can then apply to and complete a specialty specific 3- year residency program. Table 2: Pre- and Post-simulation Curriculum Survey Results

The surveys included a list of procedures and scenarios and asked participants to rate their confidence level on a scale of 1-6 (1 = no confidence/never performed, 6 = high confidence/expert level). T-test analysis of mean survey responses with respect to both pre- and post-simulation provider task comfort levels is reported with the corresponding task listed. Tasks that demonstrated statistically significant improvement in provider comfort level following simulation are bolded with a p-value < 0.05. Additionally, the differences in pre-simulation to post-simulation means are reported, with those questions showing a relative delta of > 1.50 are bolded.

The surveys included a list of procedures and scenarios and asked participants to rate their confidence level on a scale of 1-6 (1 = no confidence/never performed, 6 = high confidence/expert level). T-test analysis of mean survey responses with respect to both pre- and post-simulation provider task comfort levels is reported with the corresponding task listed. Tasks that demonstrated statistically significant improvement in provider comfort level following simulation are bolded with a p-value < 0.05. Additionally, the differences in pre-simulation to post-simulation means are reported, with those questions showing a relative delta of > 1.50 are bolded. Figure 1: Retention Data

This figure compares the average provider task comfort levels for each question on the post-simulation survey completed immediately after the course with the 3-month post-simulation survey which was later sent to participants to assess long-term retention. All questions showed an equal or great score on the 3-month survey, with the exception of pediatric IO placement, as shown above. Post-simulation survey had a total of 37 responses and the 3-month retention survey had 16 responses.

This figure compares the average provider task comfort levels for each question on the post-simulation survey completed immediately after the course with the 3-month post-simulation survey which was later sent to participants to assess long-term retention. All questions showed an equal or great score on the 3-month survey, with the exception of pediatric IO placement, as shown above. Post-simulation survey had a total of 37 responses and the 3-month retention survey had 16 responses.