Immunizations/Delivery 1

Session: Immunizations/Delivery 1

669 - What is communicated about vaccines before the clinician knocks on the door? A direct observation study of clinical staff vaccine communication prior to the patient-clinician encounter.

Friday, April 25, 2025

5:30pm - 7:45pm HST

Publication Number: 669.7052

David Higgins, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, United States; Dennis Gurfinkel, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, United States; Brooke Dorsey Holliman, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, United States; Sean T. O'Leary, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, CO, United States

David Higgins, MD, MPH

Instructor of Pediatrics

University Of Colorado School Of Medicine

Centennial, Colorado, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Evidence-based vaccine communication from the pediatric primary care team improves parental vaccine compliance, and a presumptive format for initiating vaccine discussions is associated with increased vaccination uptake. However, the vaccine communication practices of key clinic team members, including medical assistants and receptionists, remain largely unknown.

Objective: The aim of this study was to describe vaccine communication with parents among non-clinician staff (medical assistants and receptionists) during well-child encounters in pediatric practices.

Design/Methods: We conducted direct observations of non-clinician staff in 2 pediatric practices in the Denver, CO, metro area during well-child encounters from July-August (no influenza vaccine available) and October (influenza vaccine available) of 2024. Trained observers followed staff during patient registration and check-in processes until the clinician entered the room. A structured observation guide was used to record the frequency of 1) any vaccine communication and 2) the use of the evidence-based presumptive format to initiate vaccine communication. Additionally, key observations of staff communication and responses to parental vaccine concerns were recorded. Chi-square tests were used to compare the frequency of communication and presumptive format use between encounters where influenza vaccine was and was not available.

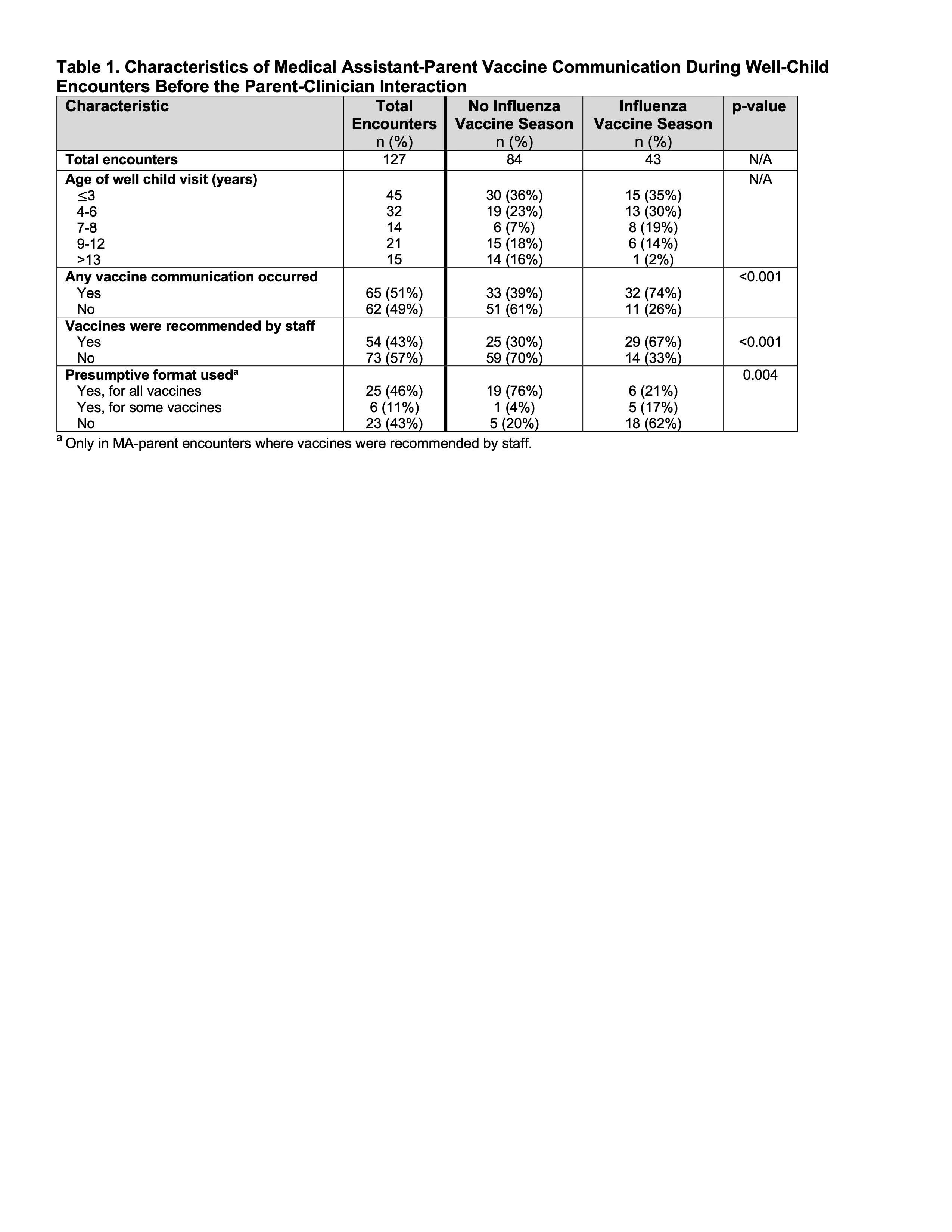

Results: We observed 174 encounters across two sites (92 at site 1 and 82 at site 2), including 127 medical assistant-parent interactions and 47 receptionist-parent interactions. Vaccine communication occurred in 51% (65/127) of all medical assistant-parent interactions compared to only 6% (3/47) of receptionist-parent interactions (p < 0.001). Vaccine communication occurred more frequently during encounters where the influenza vaccine was available (39% vs 74%; p< 0.001) (Table 1). Overall, medical assistants used a presumptive format for all vaccines 46% (25/54) of the time when vaccines were recommended. During influenza vaccine season, medical assistants used the presumptive format less frequently (76% non-flu season vs 21% flu season; p=0.004). Descriptions of key observations are shown in Table 2.

Conclusion(s): Medical assistants frequently engage in vaccine communication with parents at pediatric primary care offices; however, they underutilize evidence-based communication practices. These data highlight opportunities to expand the role of receptionists and medical assistants as part of team-based vaccine immunization delivery, as recommended by the AAP.

Table 1

Characteristics of Medical Assistant-Parent Vaccine Communication During Well-Child Encounters Before the Parent-Clinician Interaction

Characteristics of Medical Assistant-Parent Vaccine Communication During Well-Child Encounters Before the Parent-Clinician InteractionTable 2

.jpg) Key Observations of Medical Assistant-Parent Vaccine Communication During Well-Child Encounters Before the Clinician-Parent Interaction

Key Observations of Medical Assistant-Parent Vaccine Communication During Well-Child Encounters Before the Clinician-Parent Interaction