Mental Health 2

Session: Mental Health 2

773 - Impact of Perinatal Mental Health Symptoms on Infant Sleep Practices

Saturday, April 26, 2025

2:30pm - 4:45pm HST

Publication Number: 773.5119

Carolyn Ahlers-Schmidt, KUSM-W CRIBS, Wichita, KS, United States; Ashley Hervey, University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita, Wichita, KS, United States; Joy Nimeskern-Miller, KU School of Medicine-Wichita, Wichita, KS, United States; Taneisha S. Scheuermann, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, United States

Carolyn Ahlers-Schmidt, PhD (she/her/hers)

Director of Pediatric Research

KUSM-W CRIBS

University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita

Wichita, Kansas, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders impact responsiveness to infant cues and parenting choices. Infant sleep practices are associated with risk of sudden unexpected infant death (SUID). There are 3,400 cases of SUID annually in the United States and SUID is the second leading cause of death among infants in Kansas. Yet the relationship between perinatal mental health and following the American Academy of Pediatrics Safe Sleep Recommendations is unknown.

Objective: Explore the relationship between prenatal mental health symptoms and safe infant sleep learning and behaviors.

Design/Methods: This cohort study assessed data between 11/2020 and 3/2024 from the Baby Talk free prenatal education program, which includes curriculum on mental health and infant safe sleep. Baby Talk includes six 2-hour classes taught by nurses and is promoted to low-income families. It is offered in English and Spanish, and in person or virtual. Electronic data collection occurred at enrollment, after completing classes and at 6-weeks postpartum. Data collected prenatally included demographics, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Screening (EPDS) results, and intentions regarding the following behaviors: infant sleep, breastfeeding and tobacco use. EPDS responses were coded as a possible depression/anxiety if the score was 10 or more or if thoughts of self-harm were indicated. Birth outcomes and self-reported postpartum behaviors (safe sleep, tobacco, breastfeeding) were collected approximately 6-weeks postpartum. Those who reported mental health diagnoses at time of enrollment were excluded. Data were analyzed using chi-square tests. The KUMC IRB approved this secondary analysis of program data.

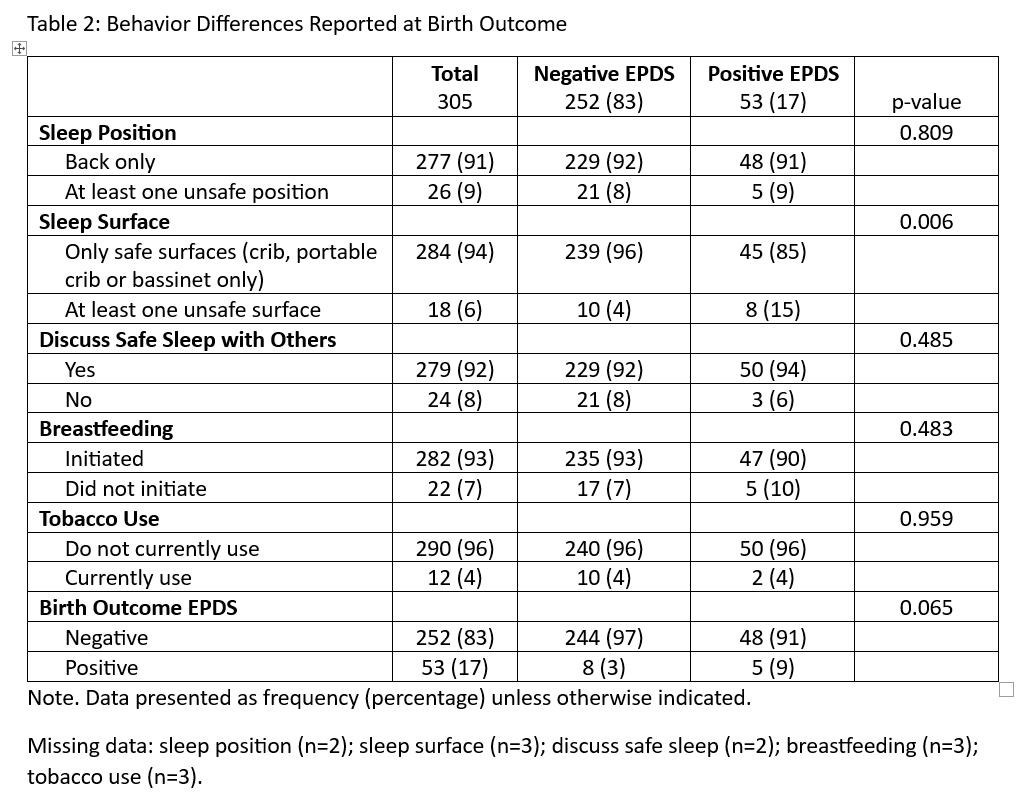

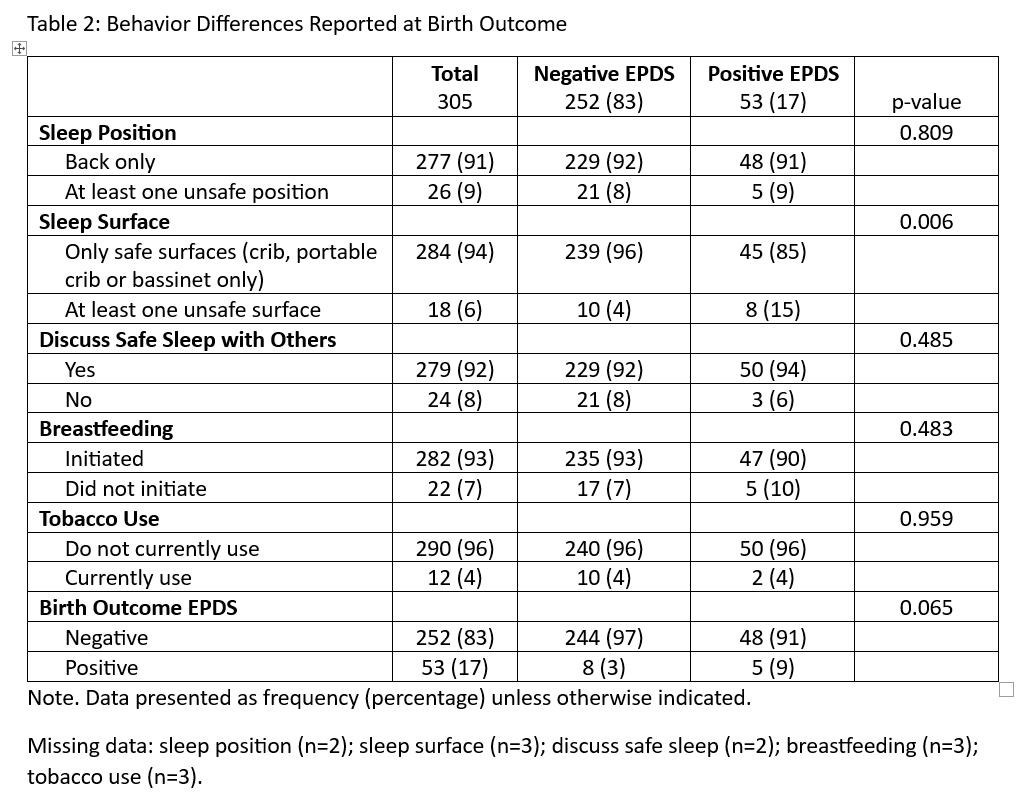

Results: Of the 305 participants included in the study, 252 (83%) had a negative EPDS and 53 (17%) screened positive. Compared to those with a negative prenatal screening, those with a positive EDPS were more likely to be younger (25 years vs 27 years) and English (vs Spanish) speaking. After Baby Talk classes, safe sleep knowledge/intentions were high regardless of screening status (Table 1). Those with a positive EPDS screen were less likely to use a recommended surface for infant sleep (e.g., crib, portable crib, bassinet) (85% vs 96%) (Table 2). No other behavioral variables were associated with elevated screening scores.

Conclusion(s): Findings suggest those experiencing mental health symptoms may be less likely to place infants to sleep on a safe surface, despite knowledge of its importance. Additional research is needed to better understand how to support those experiencing mental health challenges to follow the safe sleep recommendations.

Table 1: Knowledge and Intentions Reported on Initial and Completion Surveys (N=305)

.png)

Table 2: Behavior Differences Reported at Birth Outcome

Table 1: Knowledge and Intentions Reported on Initial and Completion Surveys (N=305)

.png)

Table 2: Behavior Differences Reported at Birth Outcome