Neonatal Quality Improvement 4

Session: Neonatal Quality Improvement 4

506 - Improving the Quality of Newborn Screening Dry Blood Spot Specimens in the Nursery

Saturday, April 26, 2025

2:30pm - 4:45pm HST

Publication Number: 506.5472

Diksha Shrestha, University of South Alabama Children's and Women's Hospital, Mobile, AL, United States; Kelechi Ikeri, University of South Alabama College of Medicine, Mobile, AL, United States; Karen Williams, University of South Alabama Children's and Women's Hospital, Mobile, AL, United States; Teneshia Edwards, University of South Alabama Children's and Women's Hospital, Mobile, AL, United States; Vicki C. Curtis, USA Children's & women's Hospital, Spanish Fort, AL, United States; Bianca M. Vamesu, University of South Alabama College of Medicine, Mobile, AL, United States; Kalsang Dolma, University of South Alabama Children's and Women's Hospital, Mobile, AL, United States; Michael Zayek, University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL, United States

- DS

Diksha Shrestha, MD

Neonatologist

University of South Alabama Children's and Women's Hospital

Mobile, Alabama, United States

Presenting Author(s)

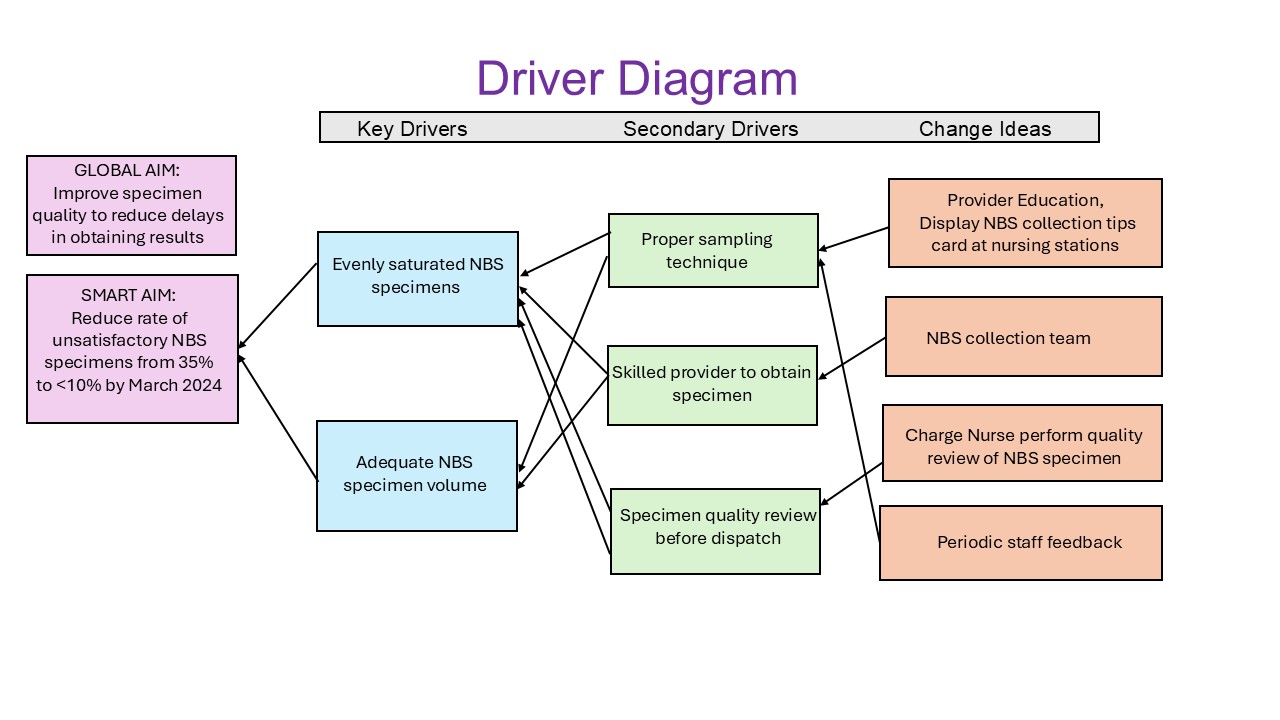

Background: The percentage of unsatisfactory dry blood spot specimens serves as a key quality indicator in national newborn screening (NBS) programs. Poor specimen quality impedes sample processing, delaying diagnosis and treatment of genetic and metabolic disorders. Thus, each state sets a benchmark for unsatisfactory specimens ( < 5% for Alabama). At our institution, the baseline rate of unsatisfactory specimens in the newborn nursery was 34.7%.

Objective: To reduce the rate of unsatisfactory NBS dry blood spot specimens in the Newborn Nursery from 34.7% to < 10% by March 2024.

Design/Methods: This quality improvement (QI) project was conducted in a 45-bed Mother-Baby unit using the Plan-Do-Study-Act model. Baseline data, collected from January 2022 to February 2023, indicated that uneven specimen saturation and inadequate specimen volume were primary contributors to poor specimen quality (Figure 1). During the QI period (March 2023 through March 2024), interventions included forming a dedicated NBS specimen collection team, having the charge nurse evaluate specimens before dispatch, and displaying educational charts on proper collection techniques at nursing stations. We tracked the monthly percentage of unsatisfactory specimens as the outcome measure, and the percentage of specimens collected by the dedicated NBS team as the process measure. However, relying on a smaller team of skilled nurses risked sampling delay. Thus, the balancing measure was the monthly percentage of initial NBS specimens obtained beyond the recommended 48-hour of life window. Measures were plotted on p-control charts across baseline (n=2458), QI (n=2372), and sustainment periods (n=514).

Results: During the QI period, the average monthly percent of unsatisfactory specimens significantly decreased from 34.7% to 5.3%, exceeding our target goal of 10 % and approaching the state benchmark of 5 %. This improvement was marked by a special cause variation and was maintained at these low levels throughout the sustainment period (Figure 2). Once established, the NBS team successfully obtained all NBS specimens. Additionally, the balancing measure dropped from 6.5 % during the baseline period to 4.7% during the QI period with special cause variation (Figure 3)

Conclusion(s): Assigning NBS collection to skilled providers, coupled with pre-dispatch inspection, dramatically improves specimen quality without causing sampling delays.

Figure 1. Key Driver Diagram

Figure 2. Outcome Measure: Unsatisfactory NBS Specimens p-chart

.jpg)

Figure 3. Balancing measure: Initial NBS obtained>48 hours of life

.jpg)