Emergency Medicine 6

Session: Emergency Medicine 6

288 - Initial Management of Children with Peripheral Facial Palsy in a Lyme Disease Endemic Area

Saturday, April 26, 2025

2:30pm - 4:45pm HST

Publication Number: 288.5309

Sophi Lederer, Boston Children's Hospital, Brookline, MA, United States; Desiree Neville, UPMC Childrens Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States; Fran Balamuth, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelhia, PA, United States; Laura Chapman, Brown Emergency Medicine, Barrington, RI, United States; Amy D. Thompson, Nemours Children's Hospital, Wilmington, DE, United States; Meagan Ladell, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milw, WI, United States; Anupam B. Kharbanda, Chidlrens Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States; Michael Monuteaux, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States; Lise E. Nigrovic, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Sophie Lederer, MD (she/her/hers)

Resident

Boston Children's Hospital

Brookline, Massachusetts, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Although Lyme disease is a common cause of peripheral facial palsy in endemic areas, treatment decisions must frequently be made before Lyme disease test results are available. The initial management of children with facial palsy in Lyme disease endemic areas has not been recently examined.

Objective: Our goal was to examine variability in the emergency department treatment of children with peripheral facial palsy in a Lyme disease endemic area and to examine time to resolution.

Design/Methods: We enrolled children ≤ 21 years of age who presented to a participating Pedi Lyme Net center from 2015 to 2023 with peripheral facial palsy (unilateral or bilateral) who had Lyme disease serology obtained. We defined Lyme disease facial palsy with a positive two-tier serologic test within 30 days of enrollment and idiopathic facial palsy when no other cause was identified. Using binary logistic regression, we identified factors independently associated with initial antibiotic treatment. For those with follow-up documented, we used Cox proportional hazards to compare the time to resolution for children with Lyme disease to idiopathic facial palsy.

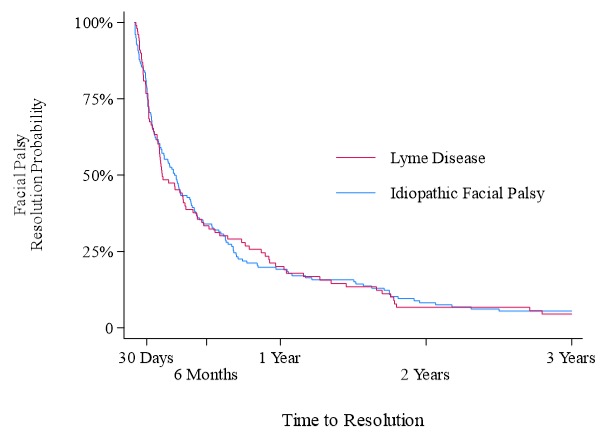

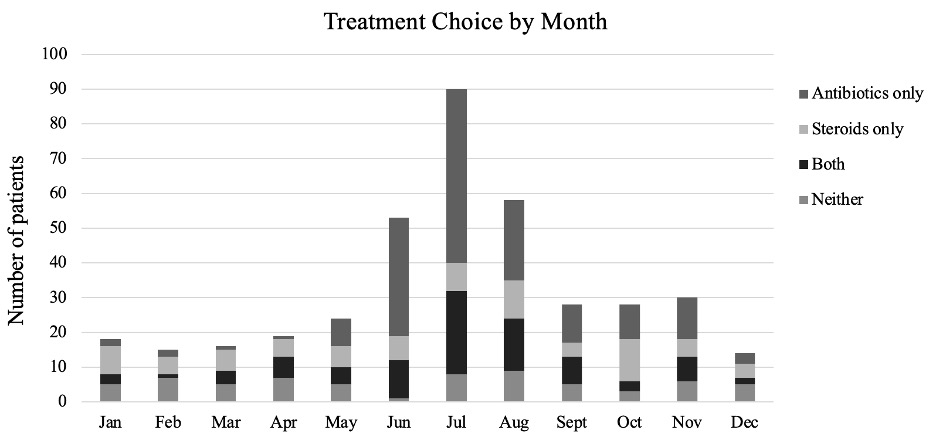

Results: Of the 393 enrolled children, 140 (35.6%) had Lyme and 253 (64.4%) idiopathic facial palsy. Overall, 246 children (62.6% of enrolled) were treated initially with antibiotics, 170 (43.3%) corticosteroids, and 89 (22.6%) both antibiotics and steroids. The majority of children with facial palsy presented during the peak Lyme season (June to October; Figure 1). Presentation during peak Lyme disease season [adjusted odds ratios (aOR) 3.86, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.47–6.03] and a history of fever (aOR 3.20, 95% CI 1.41–7.24) were associated with empiric antibiotic treatment. Among the 278 children with follow-up documented in the medical record, the time to facial palsy resolution was similar for those with Lyme and idiopathic facial palsy (hazards ratio 0.99, 95% CI 0.77–1.29; Figure 2).

Conclusion(s): Initial facial palsy treatment varied by time of year and presence of fever. Prospective trials are needed to determine impact of treatments on time to facial palsy resolution.

Initial facial palsy treatment by month of presentation

Time to documented facial palsy resolution for children with Lyme disease vs. idiopathic facial palsy