Emergency Medicine 6

Session: Emergency Medicine 6

284 - Occult Pneumonia Among Pediatric Patients: An Update in the Expanded PCV Era

Saturday, April 26, 2025

2:30pm - 4:45pm HST

Publication Number: 284.5885

Janine P.. Amirault, Boston Children's Hospital, Cambridge, MA, United States; Susan Lipsett, Boston Children's Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States; Mark Neuman, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States; Michael Monuteaux, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States; Alexander W. Hirsch, Boston Children's Hospital, Brookline, MA, United States

- JA

Janine P. Amirault, MD (she/her/hers)

Fellow

Boston Children's Hospital

Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Evaluation of fever without a source (FWS) in children sometimes includes chest radiography (CXR) to evaluate for occult pneumonia. Knowledge of the prevalence of occult pneumonia in this population, and whether there are reliable predictors of occult pneumonia, may help determine in which patients with FWS we should obtain CXR. Most studies of occult pneumonia predated widespread pneumococcal vaccination in children.

Objective: The objectives of this study were to assess the prevalence of occult pneumonia and to determine risk factors for occult pneumonia among febrile children undergoing CXR in the emergency department (ED).

Design/Methods: We analyzed prospectively collected data from children 3 months to 18 years of age with fever (based on reported history and/or triage temperature ≥ 38C) and no lower respiratory signs (crackles, wheeze, or decreased breath sounds) who underwent CXR in an urban tertiary-care pediatric ED between May 2015 and February 2024. We calculated the prevalence of occult pneumonia (radiologist-identified pneumonia in a child without lower respiratory signs). Additionally, we performed multivariable logistic regression with occult pneumonia as the dependent variable and clinical factors (patient age, presence of cough, fever duration, and presence of hypoxemia [oxygen saturation ≤ 96%]) as independent variables.

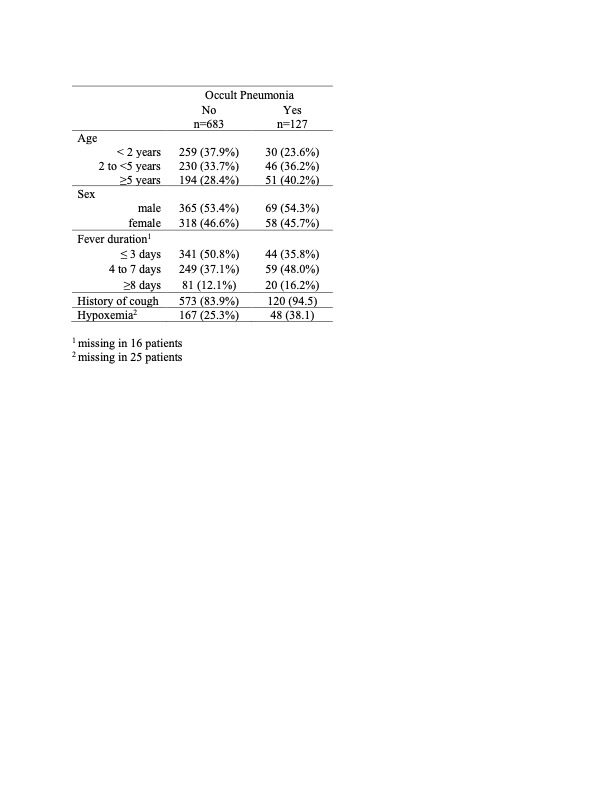

Results: Among 810 children with fever and no lower respiratory signs who underwent CXR, 127 (15.7%; 95% confidence interval [CI] 13.2-18.4%) had radiographic pneumonia (Table 1). In multivariable analysis, the odds of occult pneumonia were greater in children ≥ 5 years of age (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.3, 95% CI 1.4-3.8), as well as in those with cough (aOR 2.6, 95% CI 1.2-5.8), hypoxemia (aOR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2-2.9), and longer duration of fever (aOR 2.3 for fever ≥ 8 days, 95% CI 1.2-4.2) (Table 2).

Conclusion(s): Among a group of febrile children without lower respiratory signs who underwent CXR, one in six children had radiographic pneumonia, suggesting that occult pneumonia remains of consideration in the evaluation of FWS in children. Our study is limited by the fact that all children were already undergoing CXR, so may have had a higher pre-test probability of pneumonia. Older age, longer fever duration, history of cough, and presence of hypoxemia are associated with increased odds of occult pneumonia and therefore may serve as clinical predictors to help guide imaging to evaluate for occult pneumonia.

Table 1. Patient characteristics stratified by presence of occult pneumonia

Table 2. Multivariable logistic model evaluating the association between clinical features and occult pneumonia (n=810).

Analysis excluded 40 patients with missing data for oxygen saturation, duration of fever, or both.

Analysis excluded 40 patients with missing data for oxygen saturation, duration of fever, or both.