Adolescent Medicine 2: Disordered Eating & School-based Initiatives

Session: Adolescent Medicine 2: Disordered Eating & School-based Initiatives

595 - Screening for Eating Disorders in the Pediatric Emergency Department

Saturday, April 26, 2025

2:30pm - 4:45pm HST

Publication Number: 595.6113

Amy D. Thompson, Nemours Children's Hospital, Wilmington, DE, United States; Claire E. Loiselle, Nemours Children's Hospital, Wilmington, DE, United States; Talia Gillespie, Nemours Children's Hospital, Wilmington, DE, United States; Mackenzie Seymour, Nemours Children's Hospital, Mount Ephraim, NJ, United States

- AT

Amy Thompson, MD

Attending Physician

Nemours Children's Hospital

Wilmington, Delaware, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Early detection and treatment of eating disorders can improve prognosis and likelihood of recovery. While it is recommended that screening for disordered eating occurs during annual health supervision visits, many adolescents lack regular access to a primary care provider (PCP) and instead rely on emergency departments for care. Screening for eating disorders in the pediatric emergency department (PED) presents an opportunity for intervention, but a better understanding is needed of the prevalence and acceptability for screening in this setting.

Objective: To determine the prevalence and characteristics of PED patients who screen positive for eating disorders and to assess adolescents’ attitudes towards eating disorder screening in the PED.

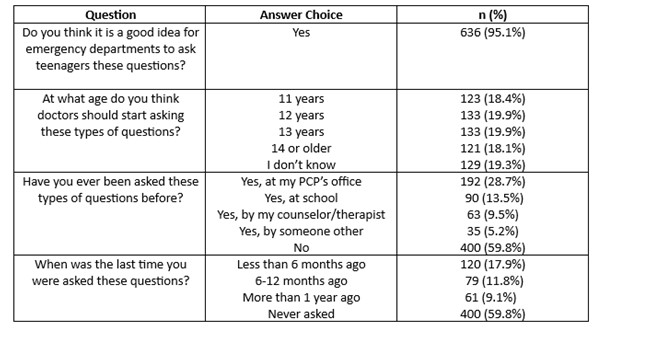

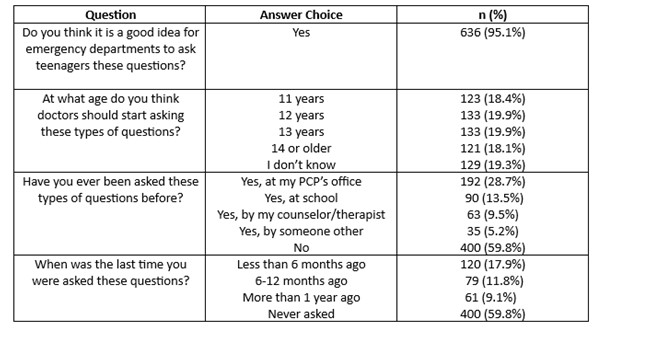

Design/Methods: This was a cross-sectional study performed in a tertiary care pediatric hospital. Patients 14-21 years who presented to the PED between 8/5/24 to 11/1/24 were eligible to complete an anonymous, self-administered REDCap questionnaire. Recruitment posters with QR codes were hung in the PED waiting room and when convenient, research staff distributed fliers and provided paper versions when requested. Informed consent was waived by the institution’s IRB. Respondents were asked demographics, frequency of preventive care, and attitudes towards screening. Participants were also asked to complete a modified version of the Sick, Control, One, Fat, Food (SCOFF) and the Adolescent Binge Eating Disorder (ADO-BED) questionnaires (Table 1). Subjects who screened positive were compared with those who screened negative in a bivariate analysis.

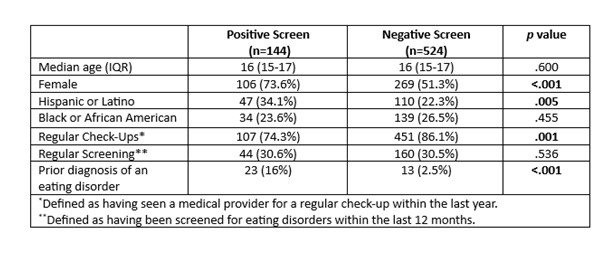

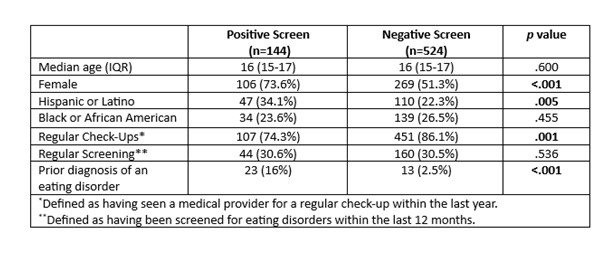

Results: Of the 668 participants [median age 16 years (IQR 15-17); 56.2% female], 36 (5.4%) reported a prior eating disorder diagnosis and 554 (82.9%) reported seeing a PCP in the last year. A total of 144 (21.6%) patients screened positive for an eating disorder [126 (18.9%) mSCOFF, 32 (4.8%) ADO-BED]. Participants that screened positive were more likely to be female (OR 2.6; 95% CI 1.8, 3.9), Hispanic (OR 1.8; 95% CI 1.2, 2.7), and report either no PCP or a last PCP visit >1 year ago [(OR 2.1; 95% 1.4, 3.3); Table 2]. Only 30% of participants reported receiving eating disorder screening in the last year. Overall, 95% adolescents reported positive attitudes toward screening for eating disorders in the PED (Table 3).

Conclusion(s): A high proportion of adolescent PED patients scored positive on eating disorder screens. Fewer than half reported ever being screened in the outpatient setting. Adolescent patients support screening for eating disorders in the PED but have varying recommendations on the appropriate age to begin screening.

Table 1: Modified SCOFF and ADO-BED Questionnaires

.jpg)

Table 2: Comparison of Patients who Screened Positive vs. Negative for Eating Disorders

(using mSCOFF and ADO-BED Questionnaires)

(using mSCOFF and ADO-BED Questionnaires)Table 3: Adolescent Responses to Eating Disorder Screening Questions

Table 1: Modified SCOFF and ADO-BED Questionnaires

.jpg)

Table 2: Comparison of Patients who Screened Positive vs. Negative for Eating Disorders

(using mSCOFF and ADO-BED Questionnaires)

(using mSCOFF and ADO-BED Questionnaires)Table 3: Adolescent Responses to Eating Disorder Screening Questions