Mental Health 2

Session: Mental Health 2

769 - Comparison of PHQ-2 and GAD-2 with EPDS and EPDS-3A in Screening for Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders

Saturday, April 26, 2025

2:30pm - 4:45pm HST

Publication Number: 769.4472

Regina J. Im, Loma Linda University Children's Hospital, Loma Linda, CA, United States; Vallent Lee, Loma Linda University Children's Hospital, Loma Linda, CA, United States

Regina J. Im, DO (she/her/hers)

Resident Physician

Loma Linda University Children's Hospital

Loma Linda, California, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Caregiver mental health disorders are adverse childhood experiences that significantly impact a child’s development and health. Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMAD) are among the most common complications in the postpartum period. Professional organizations recommend screening for postpartum depression and anxiety, but gaps exist in screening rates and underdetection is likely. While multiple screening tools have been recognized, few studies have directly compared different instruments, cutoffs for positive screens have varied, and accuracy in minority populations has not been well characterized.

Objective: We compared the performance of the shorter PHQ-2 and GAD-2 with the longer Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in screening for PMAD in a majority non-White population.

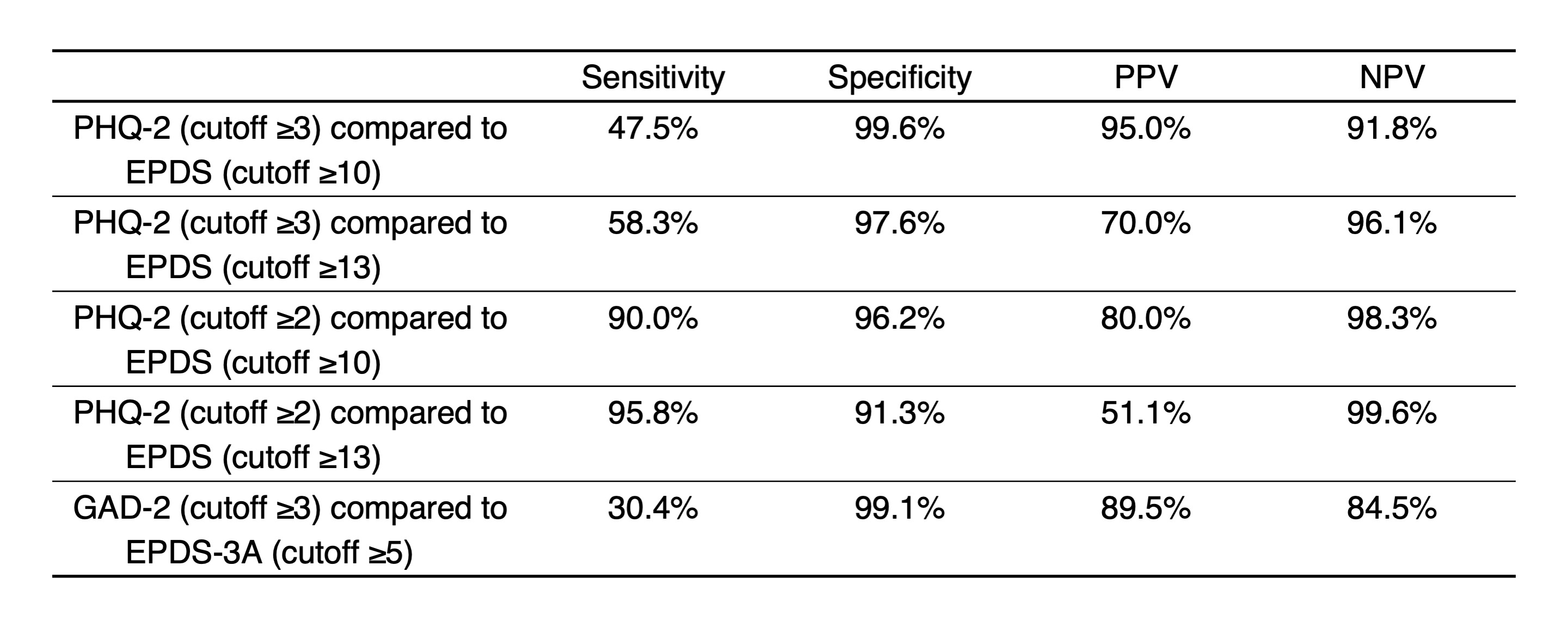

Design/Methods: We collected PHQ-2, GAD-2, and EPDS scores from 276 well-child visits for 174 infants from 3 pediatric clinics. Postpartum depression assessed by the PHQ-2 was compared to the EPDS, and postpartum anxiety assessed by the GAD-2 was compared to the EPDS-3A subscale, which consists of items 3, 4, and 5 on the EPDS. Using the EPDS and EPDS-3A as the reference standard, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of the PHQ-2 and GAD-2 were obtained. Cutoffs for abnormal screening were evaluated as follows: PHQ-2 ≥3 or ≥2, EPDS ≥10 or ≥13, GAD-2 ≥3, EPDS-3A ≥5.

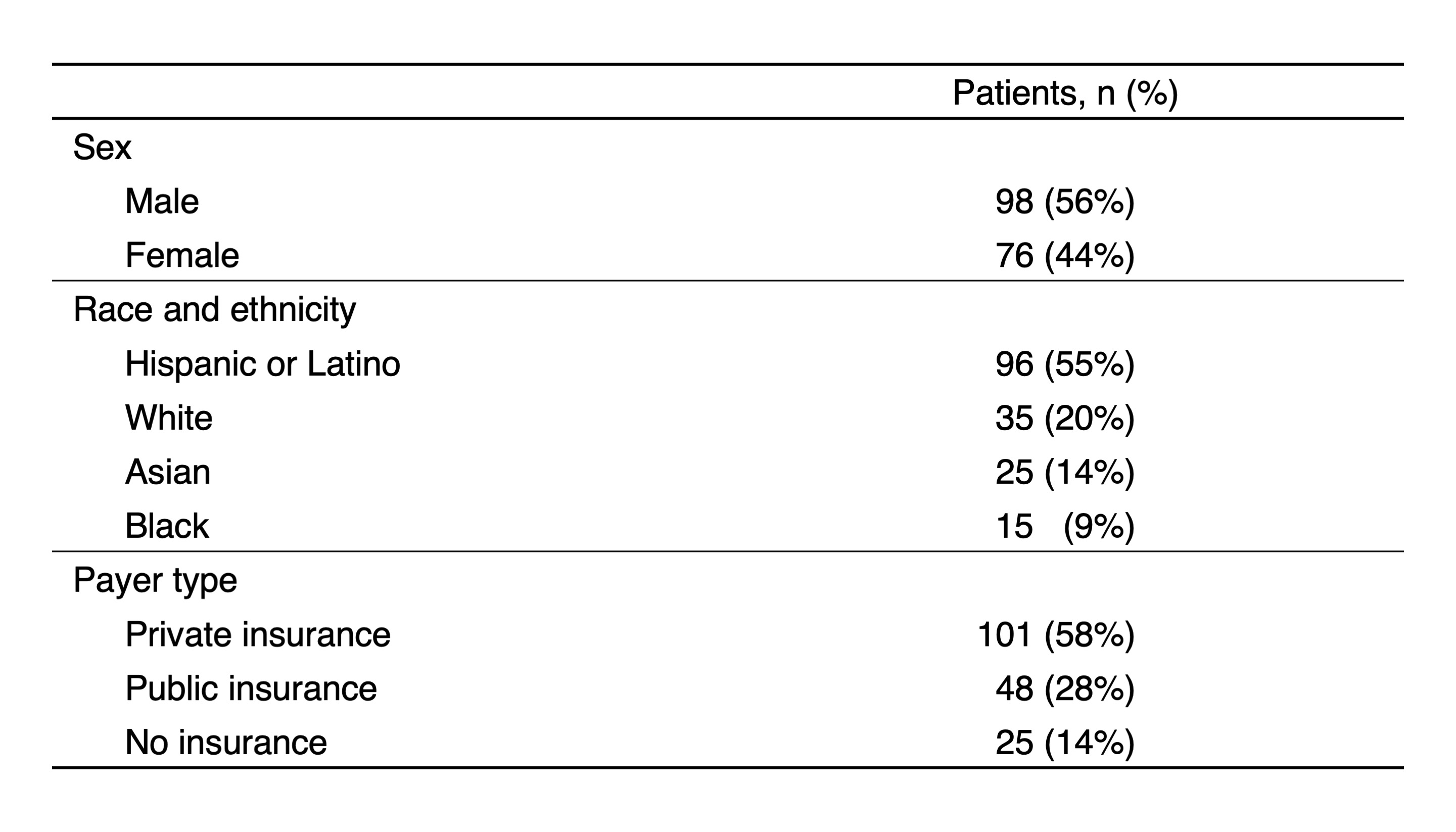

Results: Patients represented different racial and ethnic categories and payer types (Table 1). The overall prevalence of positive EPDS and EPDS-3A screenings were 14.5% and 20.29%, respectively. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were calculated (Table 2). For EPDS cutoffs of ≥10 and ≥13, PHQ-2 with cutoff of ≥3 had good specificity but poor sensitivity. Decreasing the PHQ-2 cutoff to ≥2 significantly increased its sensitivity, but significantly worsened its PPV.

Conclusion(s): At a cutoff of ≥3, PHQ-2 screening failed to identify about half of postpartum women with depression symptoms compared to screening with EPDS. With a cutoff of ≥2, detection by PHQ-2 improves, but the increase in false positives may limit its utility. In this pool of postpartum women, anxiety symptoms were more frequent than depression symptoms, suggesting a need for vigilance in screening for anxiety in the postpartum period. However, the GAD-2 performed poorly in identifying anxiety compared to the EPDS-3A. Although the shorter PHQ-2 and GAD-2 may be quicker to use, this efficiency may come with a cost of underdetection of PMAD. The EPDS may be a better modality to screen for postpartum depression and anxiety.

Infant Demographics

Performance of screening tools for postpartum depression and anxiety