Health Equity/Social Determinants of Health 1

Session: Health Equity/Social Determinants of Health 1

407 - Simultaneous Spanish Interpretation on Family-Centered Rounds and the Effects on Medication Safety, Pain Management and Discharge Readiness

Saturday, April 26, 2025

2:30pm - 4:45pm HST

Publication Number: 407.6740

Alexandra Gabrielle Kelley, UCLA Mattel Childrens Hospital, Los Angeles, CA, United States; Carlos Lerner, UCLA Mattel Childrens Hospital, Los Angeles, CA, United States; Jessica Lloyd, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, United States; Amanda Kosack, UCLA Mattel Childrens Hospital, Los Angeles, CA, United States; Audrey Kamzan, UCLA Mattel Childrens Hospital, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Alexandra Gabrielle Kelley, DO (she/her/hers)

Pediatric Hospital Medicine Fellow

UCLA Childrens Hospital

Los Angeles, California, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: When a language barrier is present, patients are more likely to experience worse health outcomes. In March 2018, in-person Equipment Assisted Simultaneous Spanish Interpretation (EASMI) on family-centered rounds (FCR) was implemented at our institution. Families self-reporting preferred language of care as Spanish during hospitalization were provided an in-person simultaneous Spanish interpreter during FCR Monday through Friday.

Objective: To determine if EASMI implementation on FCR leads to improvements in Child HCAHPS (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems) top box scores related to medication safety, pain management, or discharge readiness.

Design/Methods: This is a quantitative study utilizing pre-post intervention vs. control group analysis of Child HCAHPS scores for 13 questions in the above-listed domains. We hypothesized a priori that the introduction of EASMI would improve intervention group scores. English-speaking patients were the control group and patients preferring Spanish were the intervention group. The population studied includes pediatric admissions to a tertiary care center from March 2017 to May 2024. Mean top box scores of survey respondents were compared using chi-squared tests and corresponding p-values were calculated.

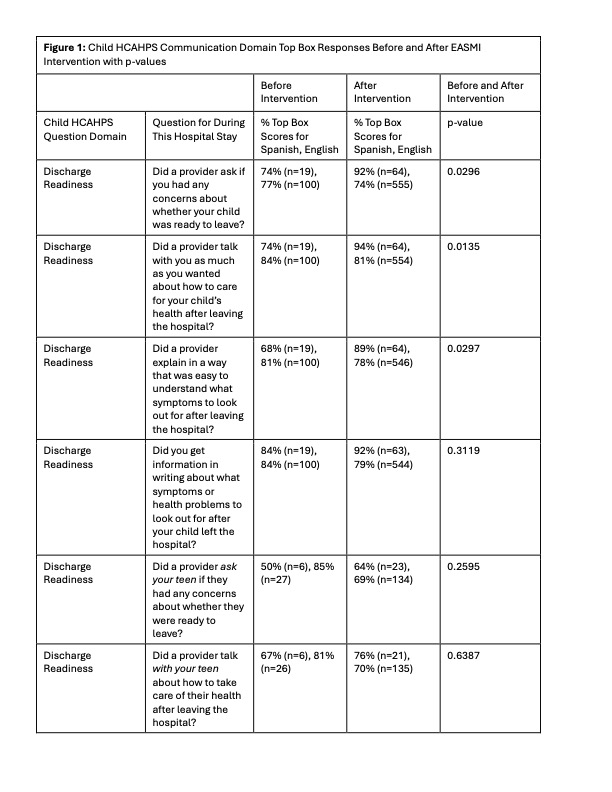

Results: For families preferring Spanish, three questions regarding discharge readiness showed statistically significant improvement in top box scores when compared pre and post implementation of EASMI. For example, “Did a provider talk with you as much as you wanted about how to care for your child’s health after leaving the hospital?” improved from 74% to 94% (p < 0.05); the remainder of outcomes are in Figure 1. Mean top box scores for control group remained the same pre and post intervention. Questions in pain management and medication safety domains did not show a statistically significant difference in the control or intervention groups.

Conclusion(s): Multiple top box patient experience scores of discharge readiness significantly improved after implementation of EASMI on FCR. However, we did not find improvements in the domains of medication safety or pain management. A potential limitation of our study is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on in-person interpreter availability. To account for this effect, we plan to present a secondary analysis of the period during the pandemic when in person interpreter use was modified. Despite limitations, our findings have the potential to contribute to best practices in equity to ensure high quality hospital discharge for patients and caregivers who speak a primary language other than English.

Figure 1: Child HCAHPS Communication Domain Top Box Responses Before and After EASMI Intervention with p-values

Figure 1 (continued): Child HCAHPS Communication Domain Top Box Responses Before and After EASMI Intervention with p-values

.jpg)

Figure 2: General setup of equipment assisted simultaneous interpretation (EASMI) on family-centered rounds (FCR)