Emergency Medicine 5

Session: Emergency Medicine 5

274 - Utilization of a CPR Coach During Pediatric Cardiac Arrests: A QI Project

Saturday, April 26, 2025

2:30pm - 4:45pm HST

Publication Number: 274.7117

Justin J. Assioun, University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, San Diego, CA, United States; Karen Yaphockun, Rady Children's Hospital San Diego/UCSD, San Diego, CA, United States; Jillian Berman, Rady Children's Hospital San Diego, San Diego, CA, United States; Daniel Roderick, Rady Children's Hospital San Diego, San Diego, CA, United States; Amy Bryl, Rady Children's Hospital/University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA, United States; Matthew Murray, University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, San Diego, CA, United States; Jackson Vane, University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, San Diego, CA, United States; Helen Harvey, Rady Children's Hospital San Diego, San Diego, CA, United States; Kathryn Hollenbach, University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, San Diego, CA, United States; Ashish Shah, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, United States

Justin J. Assioun, MD (he/him/his)

Pediatric Emergency Fellow

University of California, San Diego School of Medicine

La Jolls, California, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Consistent use of a cardiopulmonary resuscitation coach (CPRc) during pediatric cardiac arrests (CA) is not routine practice at many children’s hospitals. Compliance to pediatric advanced life support (PALS) and American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines is poor. Use of a CPRc improves the quality of CPR including chest compression (CC) fraction, CC rates, CC depth. Use of a CPRc also increases adherence to AHA guidelines and improves rates of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC).

Objective: Our SMART aim is to increase CPRc use during CA in our pediatric emergency department (PED) from ~0% to >50% by 04/2025.

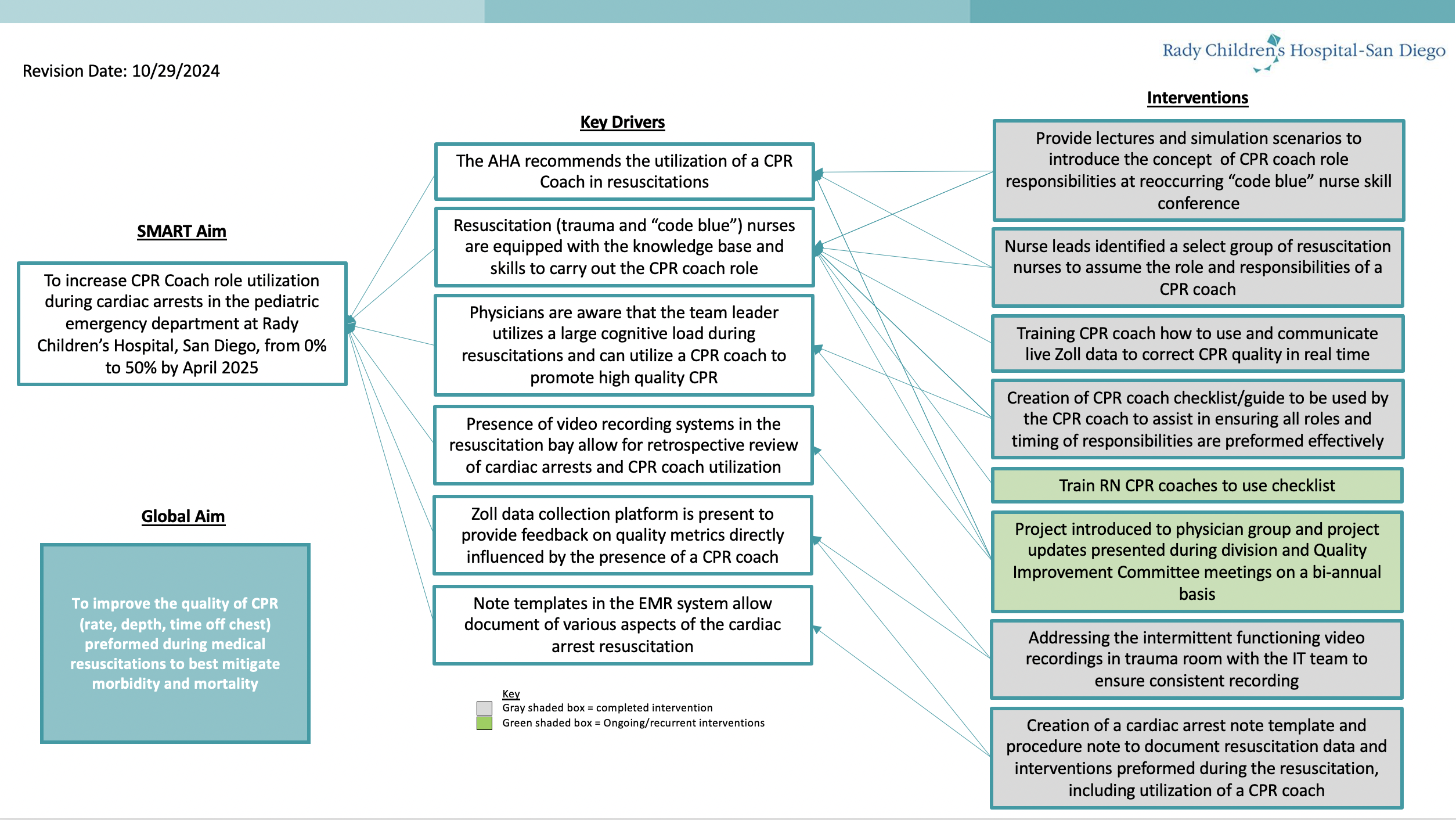

Design/Methods: This QI project was reviewed by our institutional QI committee, determined to not meet human subjects criteria and exempt from IRB review. Plan- Do- Study- Act cycles were initiated in 10/2022 and will be completed by 03/2025. A multidisciplinary team defined the responsibilities of the CPRc based on literature review. A Key Driver Diagram outlined our project drivers and interventions which included didactic teaching, simulations, creation of a CPR checklist/guide, and a CA note template (Fig 1). CPRc use was assessed through video review, CA note template documentation, and in person confirmation. Our outcome measure was CC fraction (CCF) per AHA guidelines. We used statistical process control charts to examine changes in measures over time and utilized established rules for interpretation of run charts. Statistical exact probability tests were made using STATA 18.

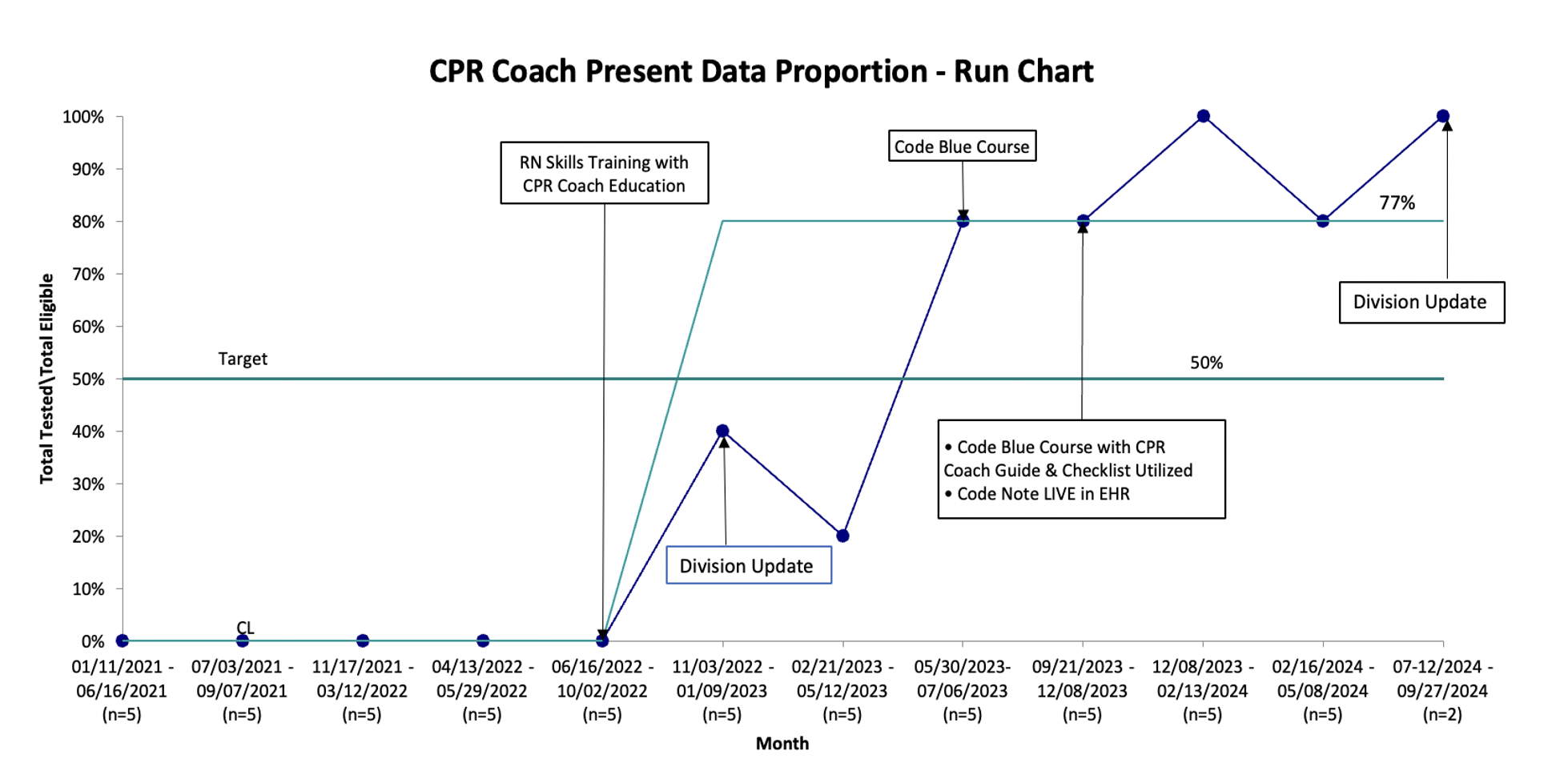

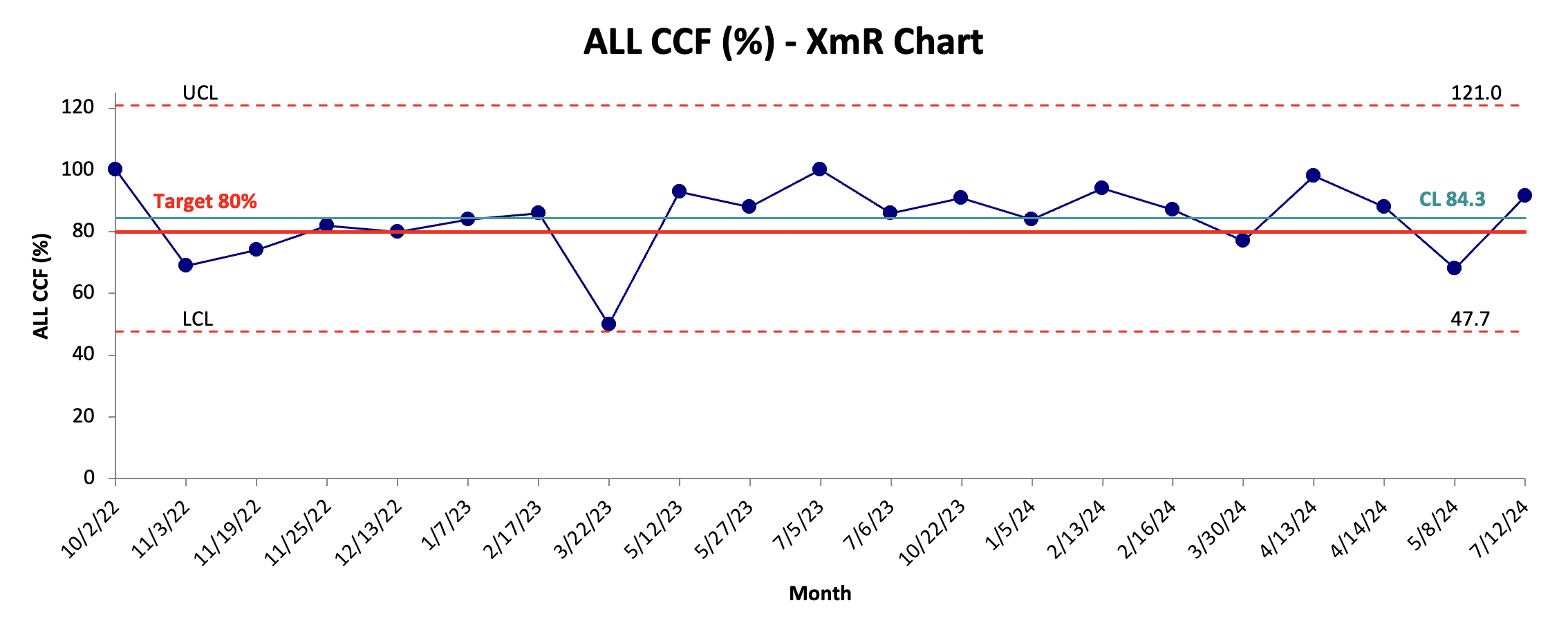

Results: From 10/2022–09/2024, the proportion of CPRc use increased from 0% to 77% (Fig 2). We noted an increase in the use of the CA note, although the current data does not inform a center line shift. CCF remained at 84.3% (Fig 3). In this period, 31 pediatric CA presented to our PED. Twenty-one resuscitations were captured by Zoll Monitor. CPRc was present in 14 resuscitations. Median CCF with and without CPRc were 86.5% and 86%, respectively (p=0.67). Nine resuscitations with a CPRc met CCF > 80%, while 7 resuscitations without a CPRc met the goal (p= 0.12). Eleven resuscitations met goal rate with a coach compared to 4 without (p= 0.35). Five cases met depth goal with a coach compared to 1 without (p =0.61).

Conclusion(s): Through the intentional creation of CPRc role and division wide education, we successfully increased our CPRc utilization. No statistical changes in CPR quality metrics noted between CA resuscitations with and without CPRc. We aim to observe our interventions for sustainability and continue to investigate the effects of CPR coach employment on the quality of CPR.

Figure 1

Key Driver Diagram

Key Driver DiagramFigure 2

CPR Coach Present Run Chart

CPR Coach Present Run Chart Figure 3

CCF% XmR Chart

CCF% XmR Chart