Hospital Medicine 4: Medical Education

Session: Hospital Medicine 4: Medical Education

163 - Resident Communication Practices During Interpreter Mediated Family-Centered Rounds

Sunday, April 27, 2025

8:30am - 10:45am HST

Publication Number: 163.6093

Joelle Kane, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, United States; Liezelle C. Lopez, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, United States; Emma Ridener, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Highland Heights, KY, United States; Angela Statile, Cincinnati Children’s, Cincinnati, OH, United States; Laura Brower, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, United States

- JK

Joelle Kane, MD, MEd (she/her/hers)

Hospitalist

Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center

Cincinnati, Ohio, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Pediatric residents are required to learn and demonstrate effective communication skills. With a growing population of linguistically diverse patients and families, these skills include working with qualified interpreters; however, standard resident education and tools to assess competency are lacking.

Objective: To understand the training needs of residents working with interpreters, we aimed to adapt an observational tool to characterize communication practices during interpreter-mediated family-centered rounds (FCR) and compare behaviors by patient language and interpreter modality.

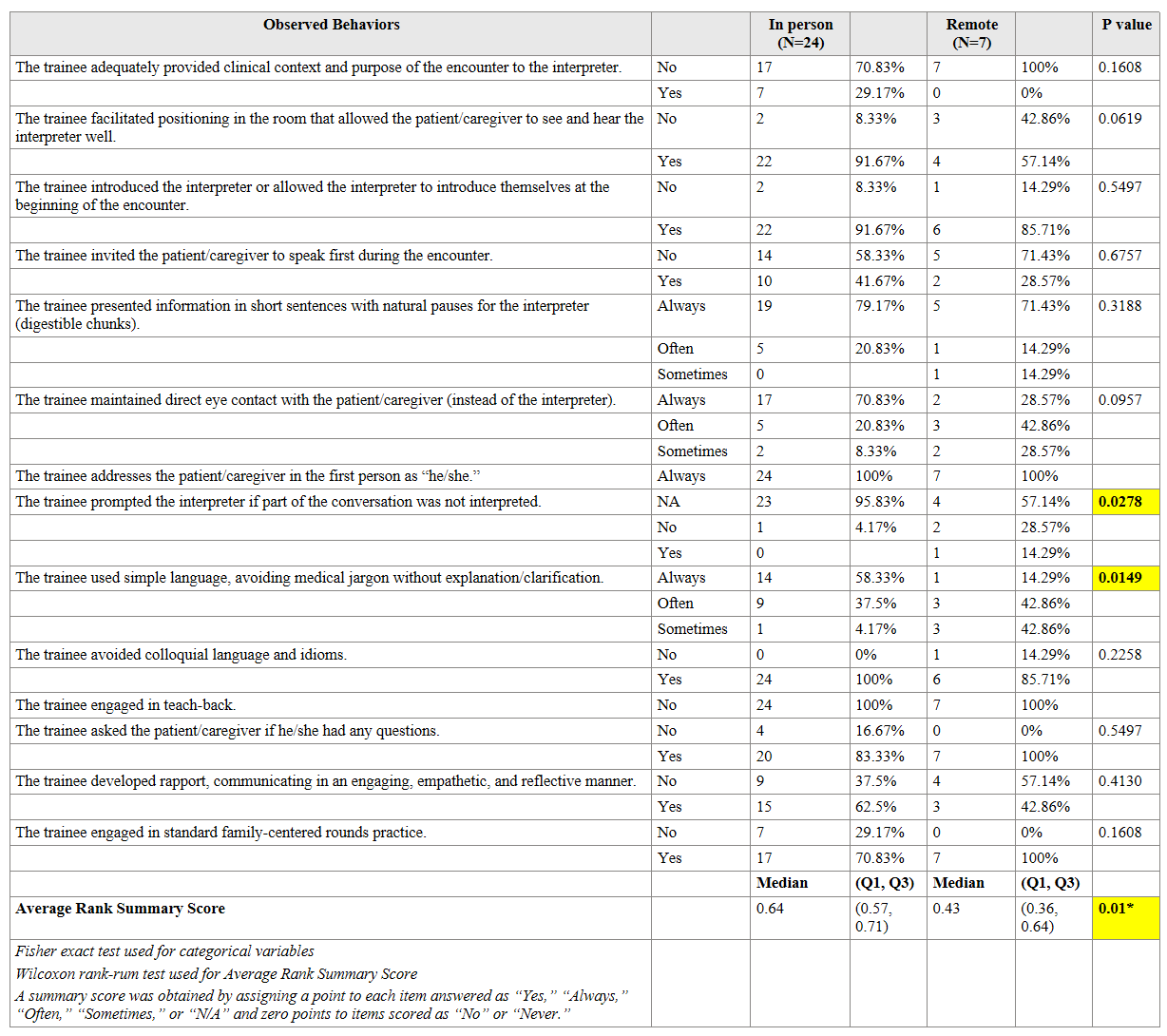

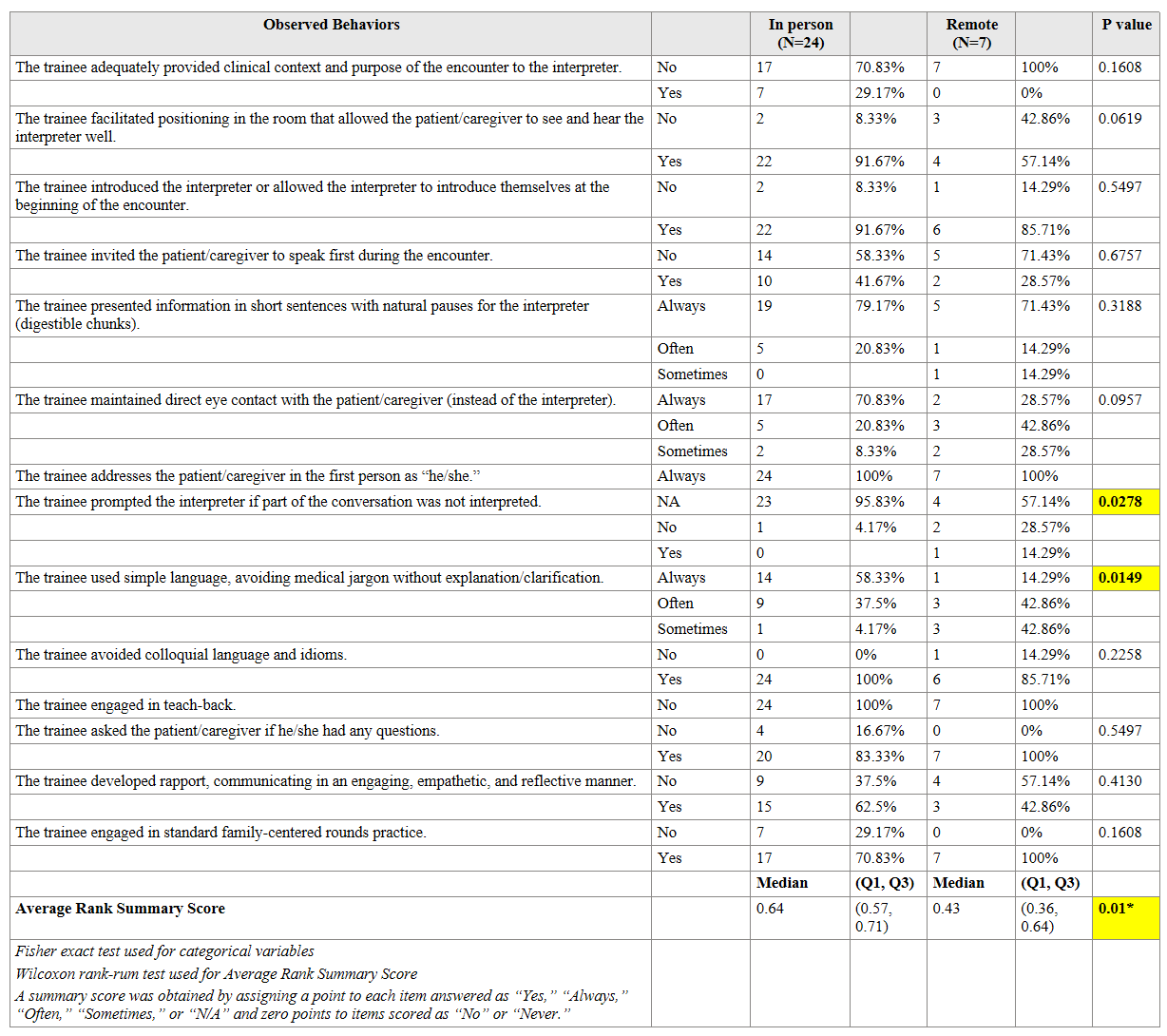

Design/Methods: This observational study was conducted on the pediatric hospital medicine service at a large free standing children’s hospital. A multidisciplinary team with content expertise adapted the existing validated Faculty Observer Rating Scale (aFORS) to evaluate communication practices during FCR. Two raters used the aFORS to independently observe and evaluate interpreter-mediated FCR. Observations of patients aged 0-18 years noted family language, interpreter modality, and year in training of the resident leading FCR. A comparative analysis of resident behaviors was performed between interpreted language groups (Spanish vs non-Spanish) and interpreter modality (in-person vs remote) using Fischer’s exact test and Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Results: We completed 31 observations. Interns led 90.3% of FCR conversations (n=28), 77.4% of encounters occurred in Spanish (n=24), and 77.4% of encounters were supported by in-person interpreters (n=24). Most best practice behaviors were demonstrated consistently across observations. We identified four behaviors performed < 75% of the time 1) providing clinical context to interpreter, 2) allowing patient/caregiver to speak first, 3) teach-back, and 4) developing rapport. No differences were identified between Spanish and other patient languages. Encounters with in-person interpreters resulted in residents using plain language p=0.01, not needing to prompt the interpreter p=0.03, and higher summary scores on the aFORS p=0.01 compared to encounters with remote interpreters.

Conclusion(s): As residents are tasked with learning inclusive communication practices for patients and families who speak a language other than English, training efforts should focus on improving partnerships with interpreters, building rapport, and using teach-back. Next steps include developing a resident curriculum on working with interpreters and evaluating the feasibility of using the aFORS for formative feedback during interpreter-mediated communication.

Table 1

.png) Adapted Faculty Observer Rating Scale & Summary of Findings

Adapted Faculty Observer Rating Scale & Summary of FindingsTable 2

Comparison of Resident Behavior by Interpreter Modality

Comparison of Resident Behavior by Interpreter Modality Table 1

.png) Adapted Faculty Observer Rating Scale & Summary of Findings

Adapted Faculty Observer Rating Scale & Summary of FindingsTable 2

Comparison of Resident Behavior by Interpreter Modality

Comparison of Resident Behavior by Interpreter Modality