Endocrinology 2

Session: Endocrinology 2

319 - Turner Syndrome beyond the binary: exploring the role of sex and gender in care for patients on the monosomy X spectrum

Sunday, April 27, 2025

8:30am - 10:45am HST

Publication Number: 319.6851

Tessa Meurer, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Milwaukee, WI, United States; Tess Jewell, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, United States; Angelica Scribner, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, United States; Madrigal von Muchow, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, United States; Kelsey Lewis, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, United States; Jennifer Rehm, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, United States

Tessa Meurer, MPH (they/them/theirs)

MD Student

University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health

Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Variations of sex characteristics (VSCs) refer to traits that do not align with binary expectations of “female” or “male” bodies. Turner syndrome (TS) is diagnosed in patients with 45XO or mosaic 45XO karyotype (i.e., on the monosomy X spectrum) and 1+ characteristic clinical manifestation. By definition, TS only includes individuals with “female phenotypes.” As a result, patients with XO/XY mosaicism labelled with a phenotype other than “female” do not have TS, despite having similar odds of clinical TS manifestations such as cardiovascular and renal malformations. It is unknown whether the use of genitalia-based diagnostic criteria for TS has unintended consequences on the care of patients on the monosomy X spectrum, particularly those with XO/XY mosaicism.

Objective: We explored clinical care received by patients on the monosomy X spectrum based on their genital phenotype, including how sex and gender were discussed with patients and families.

Design/Methods: Electronic health records from 2000-2023 at a large academic medical center were screened to identify pediatric patients on the monosomy X spectrum. Charts were reviewed for (1) TS-associated clinical screenings, (2) genital surgeries, and (3) sex and gender-related discussions. Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics and Fisher’s exact test.

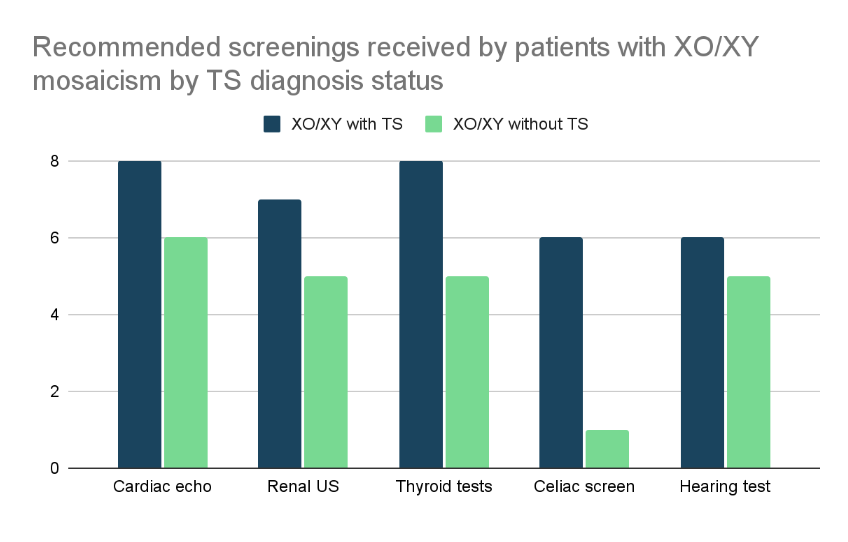

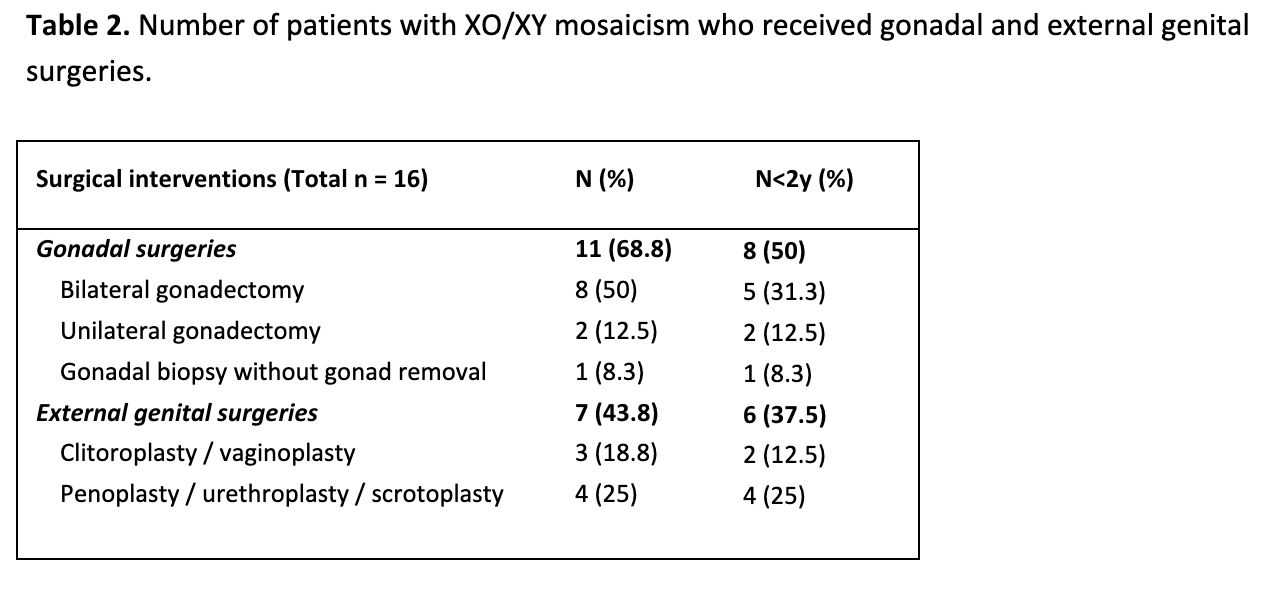

Results: Of 78 identified patients on the monosomy X spectrum, 35 (45%) had XO karyotype, 27 (35%) had XO/XX mosaicism, and 16 (21%) had XO/XY mosaicism. Of patients with XO/XY mosaicism, 10 (63%) had a diagnosed variation of external genitalia, 7 (44%) underwent external genital surgeries, and 11 (69%) underwent gonadal surgeries. Those with XO/XY mosaicism who were assigned female and diagnosed with TS were significantly more likely to receive recommended screenings than those assigned male (𝒳2=10.31, p=0.001). Discussions of sex assignment and/or gender identity were noted in clinical documentation for 7 (44%) patients with XO/XY mosaicism and were not found in any charts of patients with XO or XO/XX mosaicism.

Conclusion(s): Diagnosis of TS is contingent on a patient’s genital phenotype at birth, yet most clinical manifestations of TS have similar prevalence among all patients on the monosomy X spectrum, regardless of sex or phenotype. Patients with XO/XY mosaicism without a TS diagnosis are less likely to receive recommended screenings than those with diagnosed TS. Patients with XO/XY mosaicism often undergo irreversible surgical genital procedures early in life. Discussions of sex and gender are a neglected but potentially important component of care for families of patients with monosomy X.

MD Matriculation Confirmation with Course Completion

MD Course Completion w_ LOAs .pdf

Table 2. Number of patients with XO/XY mosaicism who received gonadal and external genital surgeries.

Figure 1. Number of patients with XO/XY mosaicism who received recommended screening by TS diagnosis status