Child Abuse & Neglect 1

Session: Child Abuse & Neglect 1

346 - Protective Factors Against Child Maltreatment Among Postpartum Mothers.

Sunday, April 27, 2025

8:30am - 10:45am HST

Publication Number: 346.6164

Henry T. Puls, Children's Mercy Kansas City, Kansas City, MO, United States; Elizabeth Grady, Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, LEES SUMMIT, MO, United States; Matthew Hall, Children's Hospital Association, Lenexa, KS, United States; Cristy Toburen, Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Shawnee, KS, United States; Ann Mattison, Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, MO, United States; Margaret Mann, Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, MO, United States; Jennifer Anderson, Children’s Mercy Hospital, Platte city, MO, United States; Katie J. Hocker, Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, MO, United States; Francesca Donohue, Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Overland Park, KS, United States; Heather Williams, Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, MO, United States; Jessica Sprague-Jones, University of Kansas Center for Public Partnerships and Research, Lawrence, KS, United States; Jim Anderst, Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, MO, United States

- HP

Henry T. Puls, MD

Professor of Pediatrics

Children's Mercy Kansas City

Kansas City, Missouri, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Risk for child maltreatment results from the confluence of both risk and protective factors (PF). However, little is known about the prevalence of and disparities in PF across maternal characteristics.

Objective: To compare the frequency of PF against child maltreatment between mothers with and without risk factors for child maltreatment and across race and ethnicity.

Design/Methods: This was a prospective cross-sectional study of English and Spanish speaking postpartum mothers enrolled in June 2023 – October 2024 during their birth hospitalization at a Midwest urban academic hospital. The previously validated Protective Factors Survey, 2nd Edition measured 4 subscales of PF against child maltreatment on a scale of 0 to 4, with 4 being optimal: (1) family functioning/resilience (FFR), (2) nurturing/attachment (NA), (3) social supports (SS), and (4) concrete supports (CS). Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests made bivariate comparisons within each PF subscale. PF subscale scores were then dichotomized into optimal (=4) and suboptimal ( < 4) for multivariable logistic regression to estimate the adjusted associations between maternal demographics and risk factors with PF subscale scores.

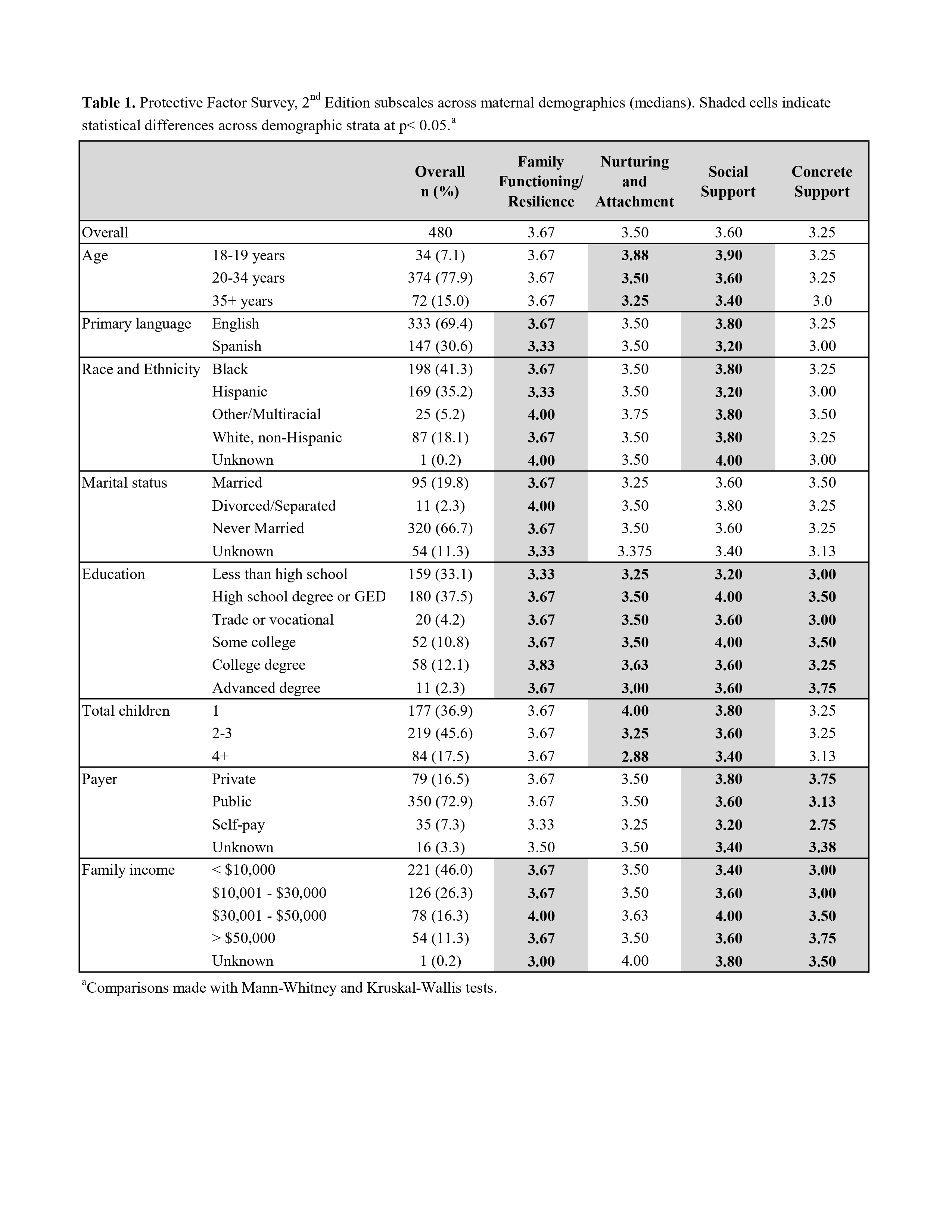

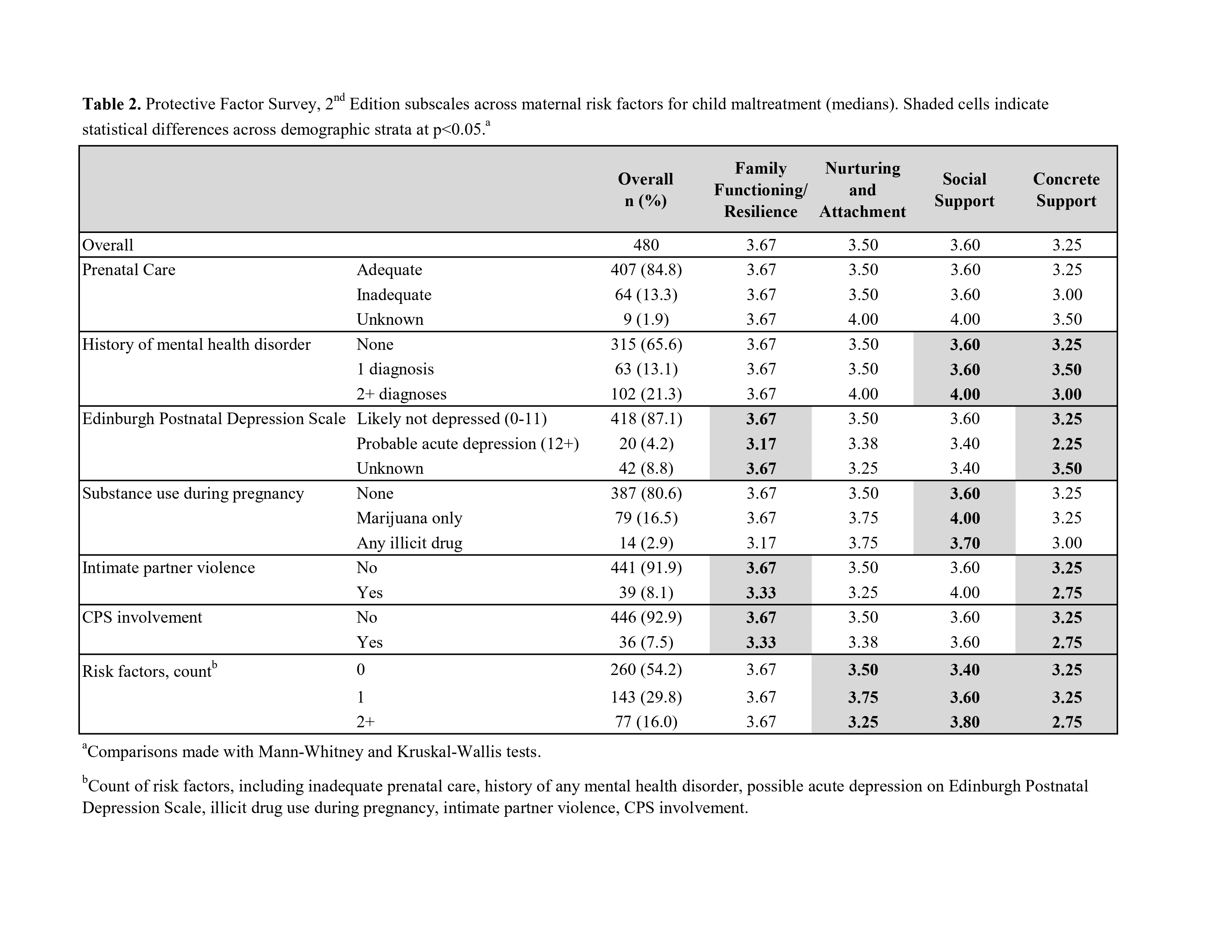

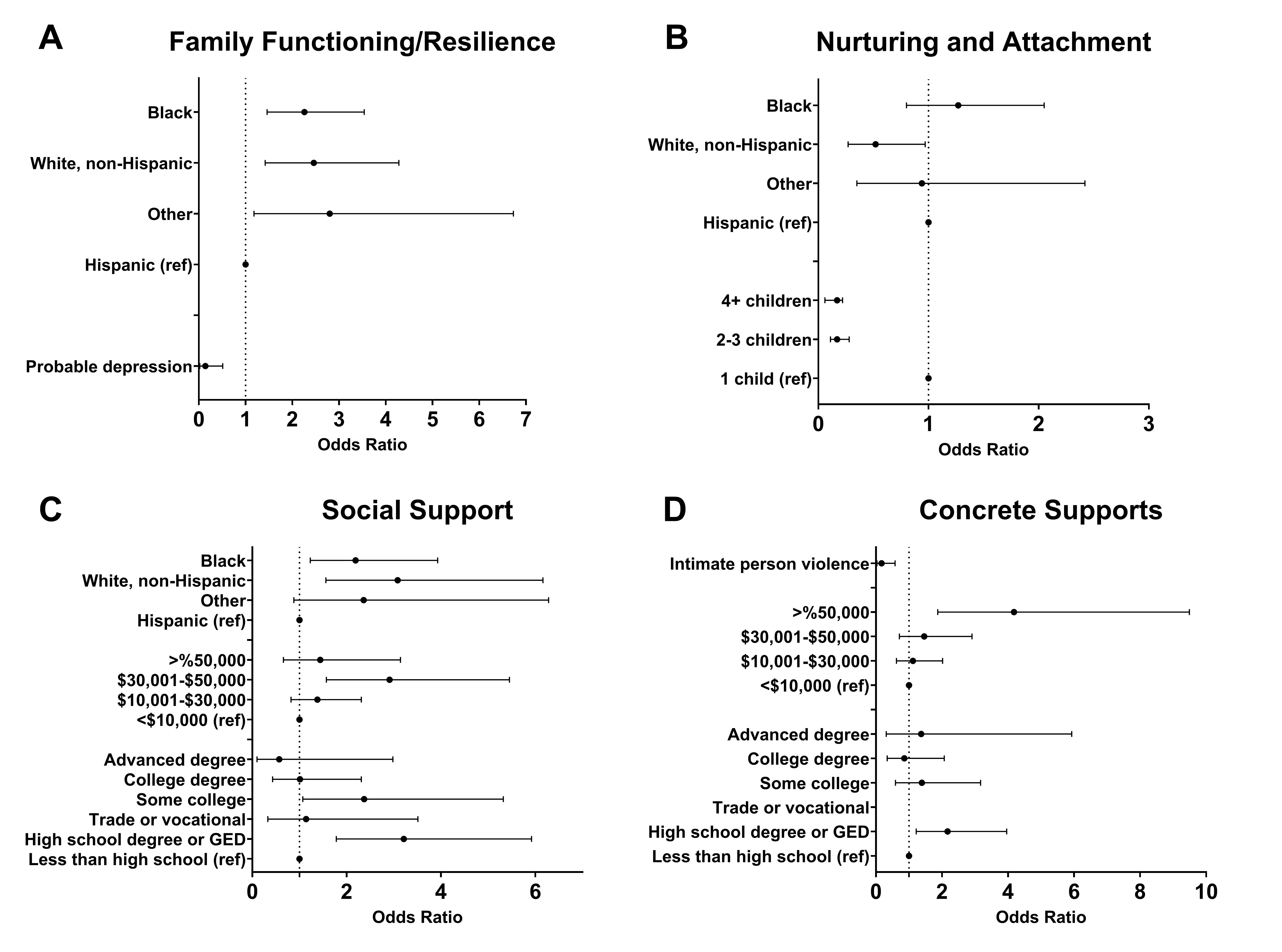

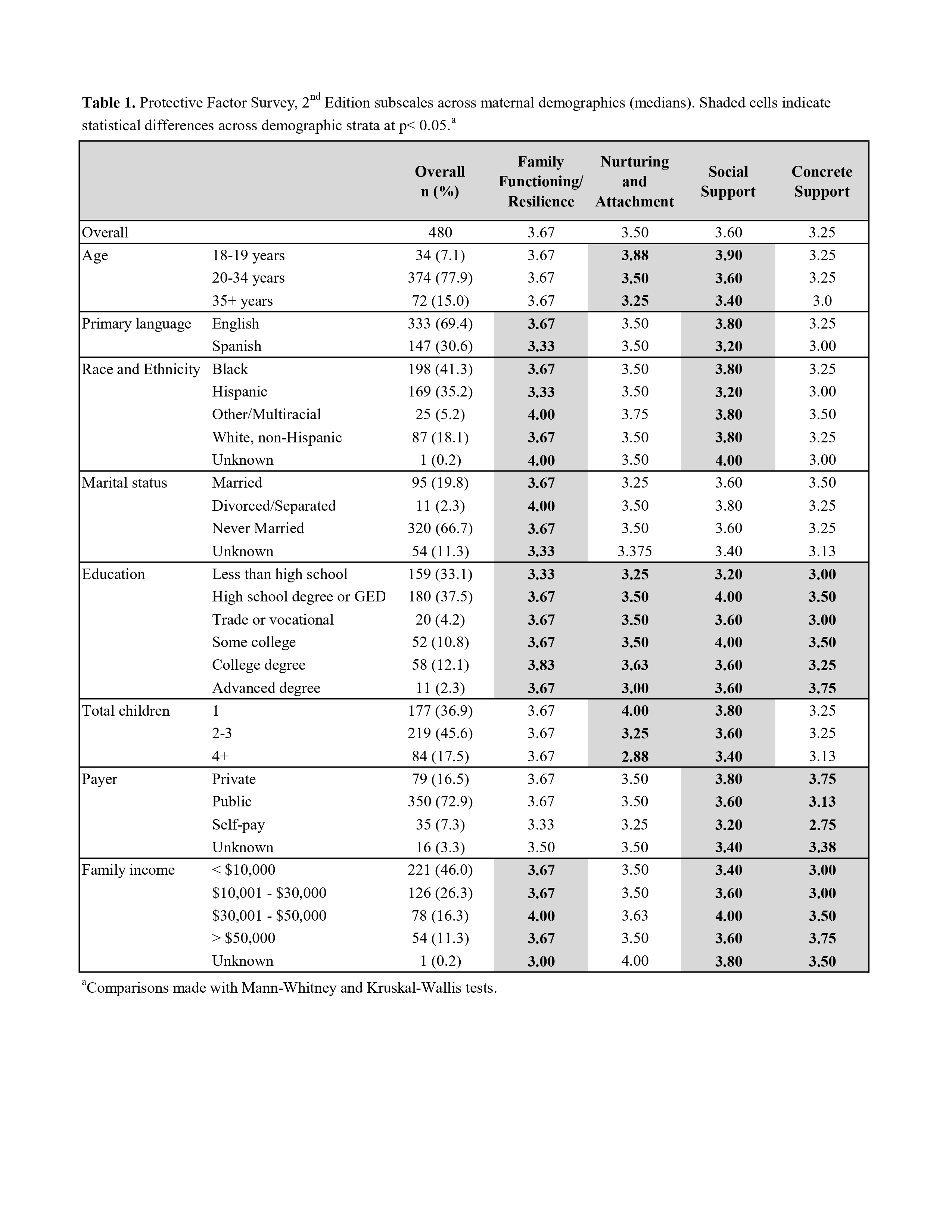

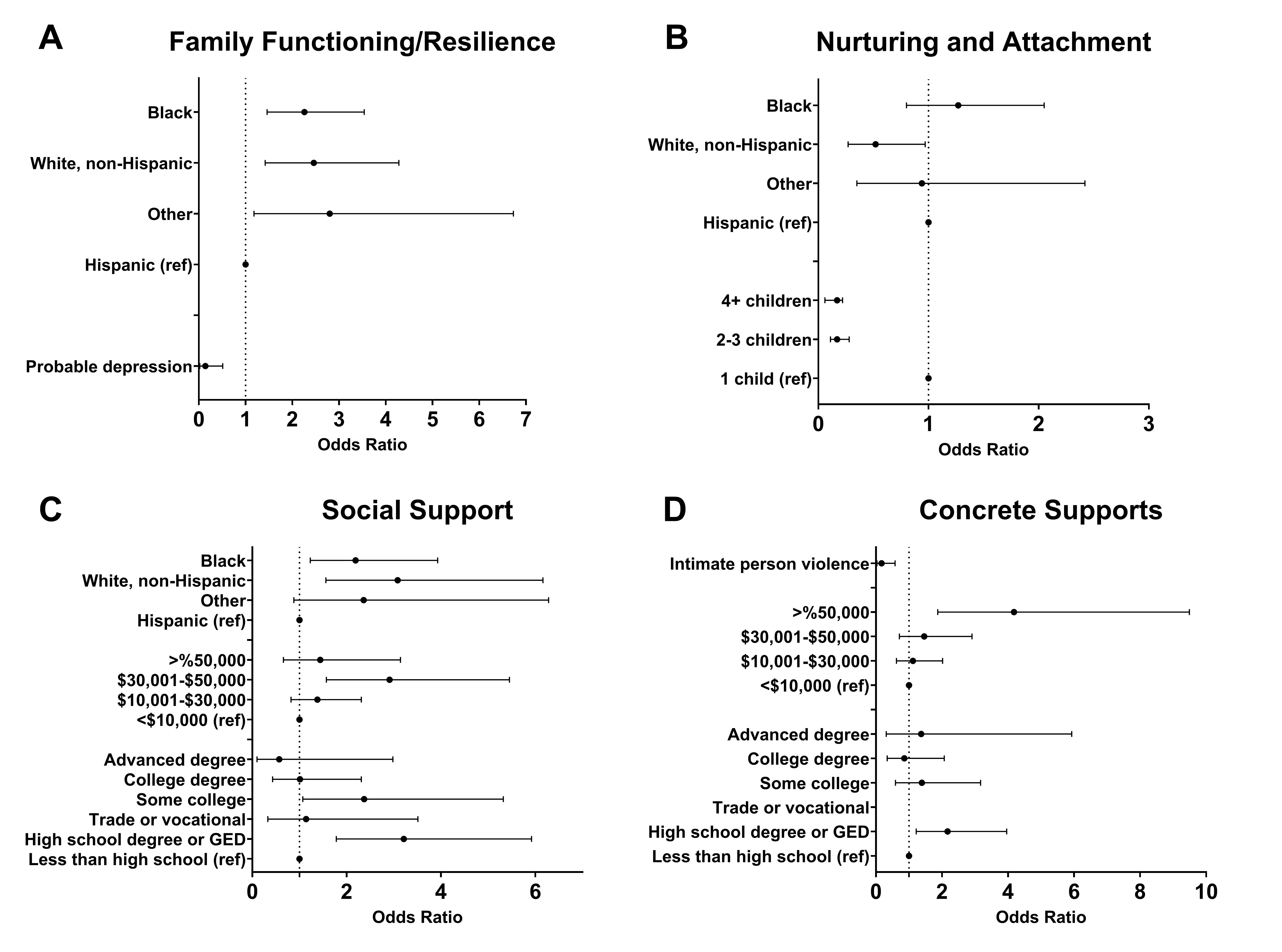

Results: There were 480 mothers enrolled who were most often English speaking (69.4%), Black (41.3%), with high school degree or GED (37.5%), 2-3 total children (45.6%), and family income <$10,000 (46.0%). A minority had positive postnatal depression screening (4.2%), 8.1% had experienced IPV, and 16.5% used marijuana only and 2.9% used an illicit drug during pregnancy. At least 2 PF subscale scores varied across all maternal demographics (Table 1). At least 1 PF subscale varied across all risk factors except adequacy of prenatal care (Table 2). Mothers with positive postnatal depression screening had lower odds of reporting optimal FFR (0.14 [95% CI 0.02, 0.51]) and mothers experiencing IPV had lower odds of reporting optimal CS (0.17 [95% CI 0.03, 0.58]; Figure). Compared to Hispanic mothers, Black mothers reported greater odds of optimal FFR (2.26 [95% CI 1.46, 3.54]) and SS (2.19 [95% CI 1.23, 3.93), while non-Hispanic White mothers reported greater odds of FFR (2.46 [95% CI 1.42, 4.28]) and SS (3.08 [95% CI 1.56, 6.16]), but lower odds of NA (0.52 [95% CI 0.27, 0.97]).

Conclusion(s): PF vary considerably across maternal demographics; most notably with Black and White mothers reporting greater PF compared to Hispanic mothers. Mothers with positive depression screening, IPV, and more total children reported lower PF and may particularly benefit from prevention efforts intended to promote PF, such as home visiting.

Table 1

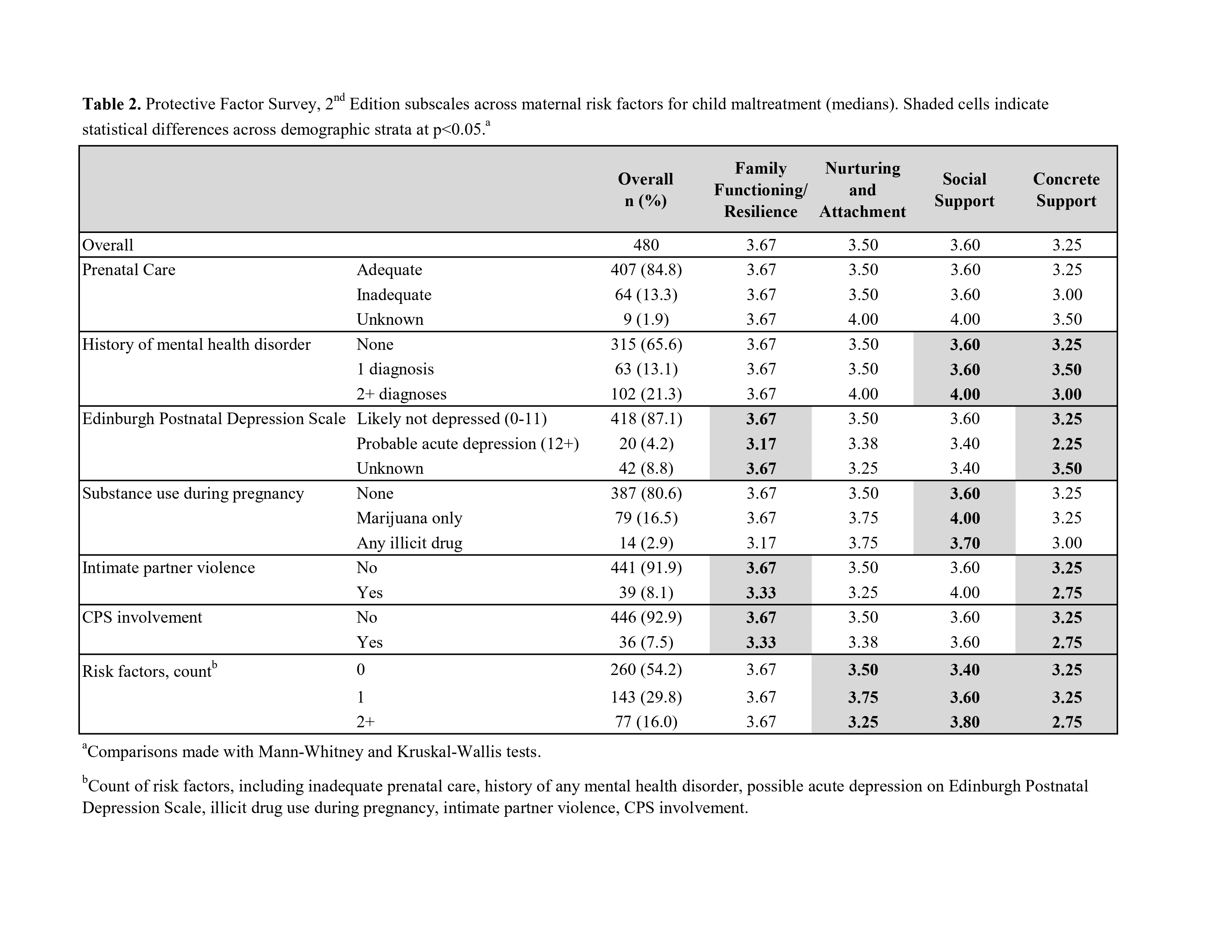

Table 2

Figure

Adjusted odds of optimal PF subscale scores, (A) Family Functioning/Resilience, (B) Nurturing and Attachment, (C) Social Support, (D) Concrete Supports. All maternal demographics and risk factors with near significance in bivariate analysis (i.e., p< 0.1) were included in the initial multivariable logistic regression models. Race and ethnicity was of specific interest as a primary exposure and was initially included in all 4 subscale regression models. Non-significant covariates were removed using backwards elimination.

Adjusted odds of optimal PF subscale scores, (A) Family Functioning/Resilience, (B) Nurturing and Attachment, (C) Social Support, (D) Concrete Supports. All maternal demographics and risk factors with near significance in bivariate analysis (i.e., p< 0.1) were included in the initial multivariable logistic regression models. Race and ethnicity was of specific interest as a primary exposure and was initially included in all 4 subscale regression models. Non-significant covariates were removed using backwards elimination. Table 1

Table 2

Figure

Adjusted odds of optimal PF subscale scores, (A) Family Functioning/Resilience, (B) Nurturing and Attachment, (C) Social Support, (D) Concrete Supports. All maternal demographics and risk factors with near significance in bivariate analysis (i.e., p< 0.1) were included in the initial multivariable logistic regression models. Race and ethnicity was of specific interest as a primary exposure and was initially included in all 4 subscale regression models. Non-significant covariates were removed using backwards elimination.

Adjusted odds of optimal PF subscale scores, (A) Family Functioning/Resilience, (B) Nurturing and Attachment, (C) Social Support, (D) Concrete Supports. All maternal demographics and risk factors with near significance in bivariate analysis (i.e., p< 0.1) were included in the initial multivariable logistic regression models. Race and ethnicity was of specific interest as a primary exposure and was initially included in all 4 subscale regression models. Non-significant covariates were removed using backwards elimination.