Child Abuse & Neglect 1

Session: Child Abuse & Neglect 1

347 - Sentinel Injury Recognition in Child Physical Abuse: A Tiered Complexity Reverse Boot Camp Simulation Curriculum

Sunday, April 27, 2025

8:30am - 10:45am HST

Publication Number: 347.6690

Jane M. Hayes, Mass General Brigham, Woburn, MA, United States; Michael D. Fishman, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States; Alexander W. Hirsch, Boston Children's Hospital, Brookline, MA, United States; Gareth Parry, Cambridge Health Alliance - - Cambridge, MA, Cambridge, MA, United States; Danielle Turpin, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States; Alexa I. Paone, Boston Childrens Hospital, Salem, MA, United States; Anne Fox, Boston Children's Hospital, Brookline, MA, United States; Joshua Nagler, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States; Katherine Canty, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Michael D. Fishman, MD (he/him/his)

Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellow

Boston Children's Hospital

Boston Children's Hospital, Boston Medical Center

Boston, Massachusetts, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Pediatric training often incorporates limited content related to child abuse, which may inhibit the identification of concerning physical exam findings. Sentinel injuries are mild superficial injuries, frequently appearing as bruising and oral injuries that precede more severe abuse. Clinicians may be able to prevent escalating physical child abuse by correctly recognizing these injuries.

Objective: To develop, implement, and assess a tiered complexity child abuse simulation curriculum to improve trainee knowledge of sentinel injuries in child abuse.

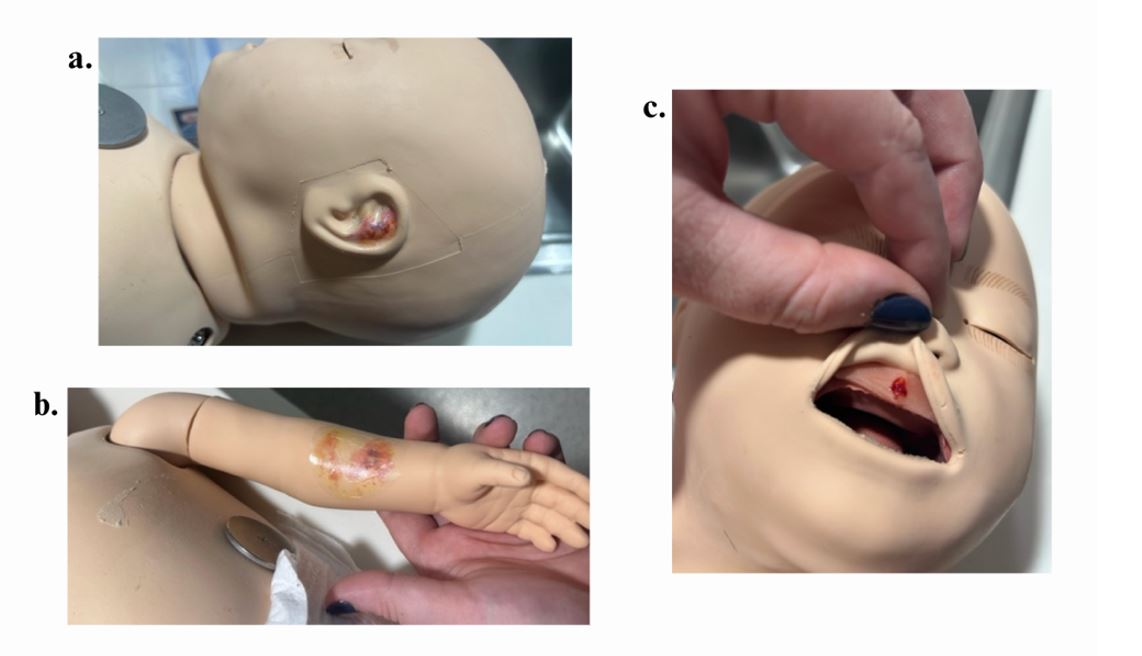

Design/Methods: We created a one-hour reverse bootcamp curriculum for pediatric and emergency medicine residents and pediatric emergency medicine fellows that was tailored to level of training. The curriculum consisted of a simulation with debrief, didactic session, and case study. The simulation utilized an infant manikin and parent actor. The case involved a four-month-old twin infant presenting to the emergency department with respiratory symptoms. Moulage was used to portray one of three sentinel injuries: an ear bruise, forearm bruise, or frenula injury (Figure 1). A pre-test was used to evaluate prior exposure to child abuse instruction. A retrospective pre- and post-test using Likert scale items and 5 multiple choice questions were used to assess differences in comfort and knowledge regarding child abuse recognition, and perceived curricular impact. Questions were developed by child abuse experts. Likert scale items were dichotomized to agree or neutral/disagree.

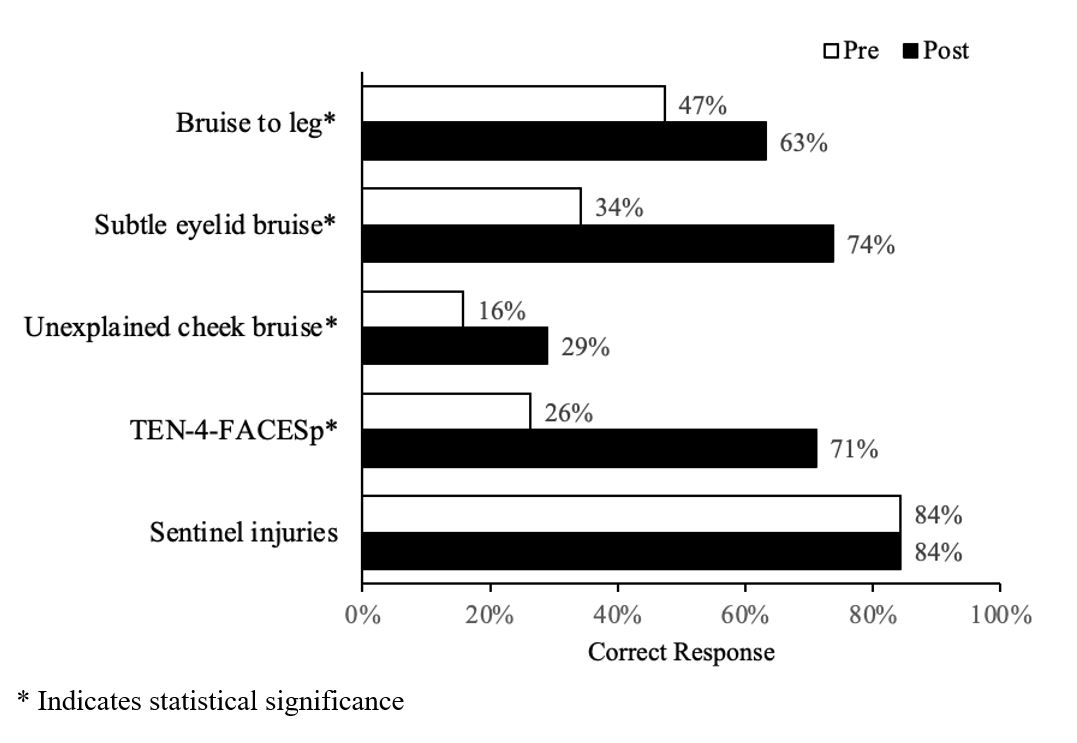

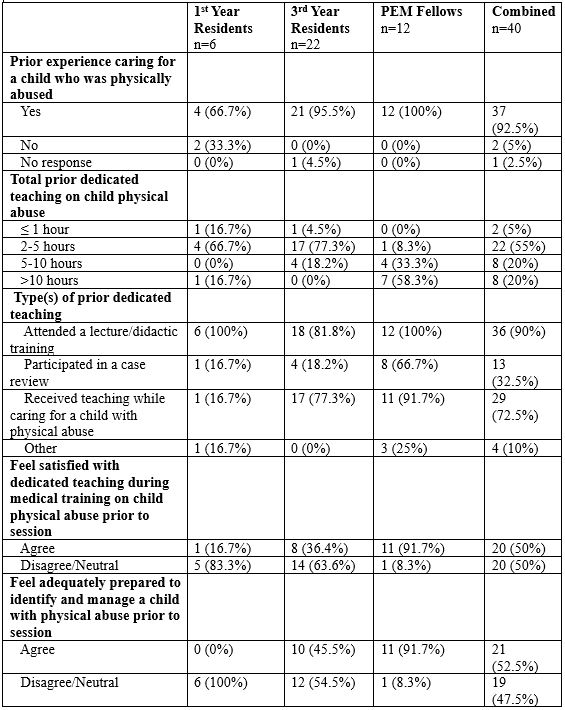

Results: There were 9 sessions reaching 43 residents and fellows with 40 linked surveys included in analysis (Table 1). Most participants (60%) received a maximum of 5 hours of prior dedicated teaching on child physical abuse. Overall, there were statistically significant increases in the percentage of knowledge-based questions answered correctly following participation (Figure 2). Only half (52.5%) of participants felt prepared to identify and manage a child with physical abuse prior to the session, but all (100%) participants indicated agreement that the curriculum increased their knowledge of the evidence behind sentinel injury recognition and screening.

Conclusion(s): We implemented a tiered complexity simulation curriculum that significantly increased trainees’ ability to correctly answer knowledge-based questions regarding recognition and management of sentinel injuries. Both residents and fellows found value in the curriculum and felt it increased their knowledge of child physical abuse and ability to recognize sentinel injuries.

Figure 1.

Simulation manikin moulage: a. ear bruise; b. forearm bruise; and c. frenula injury.

Simulation manikin moulage: a. ear bruise; b. forearm bruise; and c. frenula injury.Figure 2.

Percentage of participants who correctly answered knowledge-based questions on linked pre- and post-survey.

Percentage of participants who correctly answered knowledge-based questions on linked pre- and post-survey.Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

Participant characteristics.