Breastfeeding/Human Milk 2

Session: Breastfeeding/Human Milk 2

648 - What is effective communication in breastfeeding care? Perspectives from Latina women

Saturday, April 26, 2025

2:30pm - 4:45pm HST

Publication Number: 648.7028

Deanna Nardella, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States; Sofia I. Morales, Yale School of Public Health, Woodbridge, CT, United States; Rafael Pérez-Escamilla, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT, United States; Genesis A. Vicente, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, United States; Leslie Brown, Yale School of Public Health, West Haven, CT, United States; Natasha J.. Ray, New Haven Healthy Start, New Haven, CT, United States; Kathleen O. Duffany, Yale School of Public Health, West Hartford, CT, United States; Elizabeth Rhodes, Emory University Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, GA, United States

- DN

Deanna Nardella, MD MHS (she/her/hers)

Instructor of Pediatrics

Yale School of Medicine

New Haven, Connecticut, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Women want person-centered maternity care, including breastfeeding care. Although effective communication is critical to person-centered care, little data exist around effective communication in breastfeeding care from the perspectives of women, specifically Latina women in the United States (US) who experience breastfeeding inequities.

Objective: Our study identifies (a) what constitutes effective communication in breastfeeding care and (b) which provider practices promote or hinder effective communication in breastfeeding care across the pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum periods to US Latina women.

Design/Methods: We conducted a secondary analysis of data from a community-engaged study that included semi-structured interviews in English or Spanish with Latina women from low-income households in Connecticut. Women were asked about communication experiences with healthcare providers during breastfeeding care across the pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum periods. A modified grounded theory approach was used to analyze the data and develop a conceptual framework depicting key themes of effective communication in breastfeeding care.

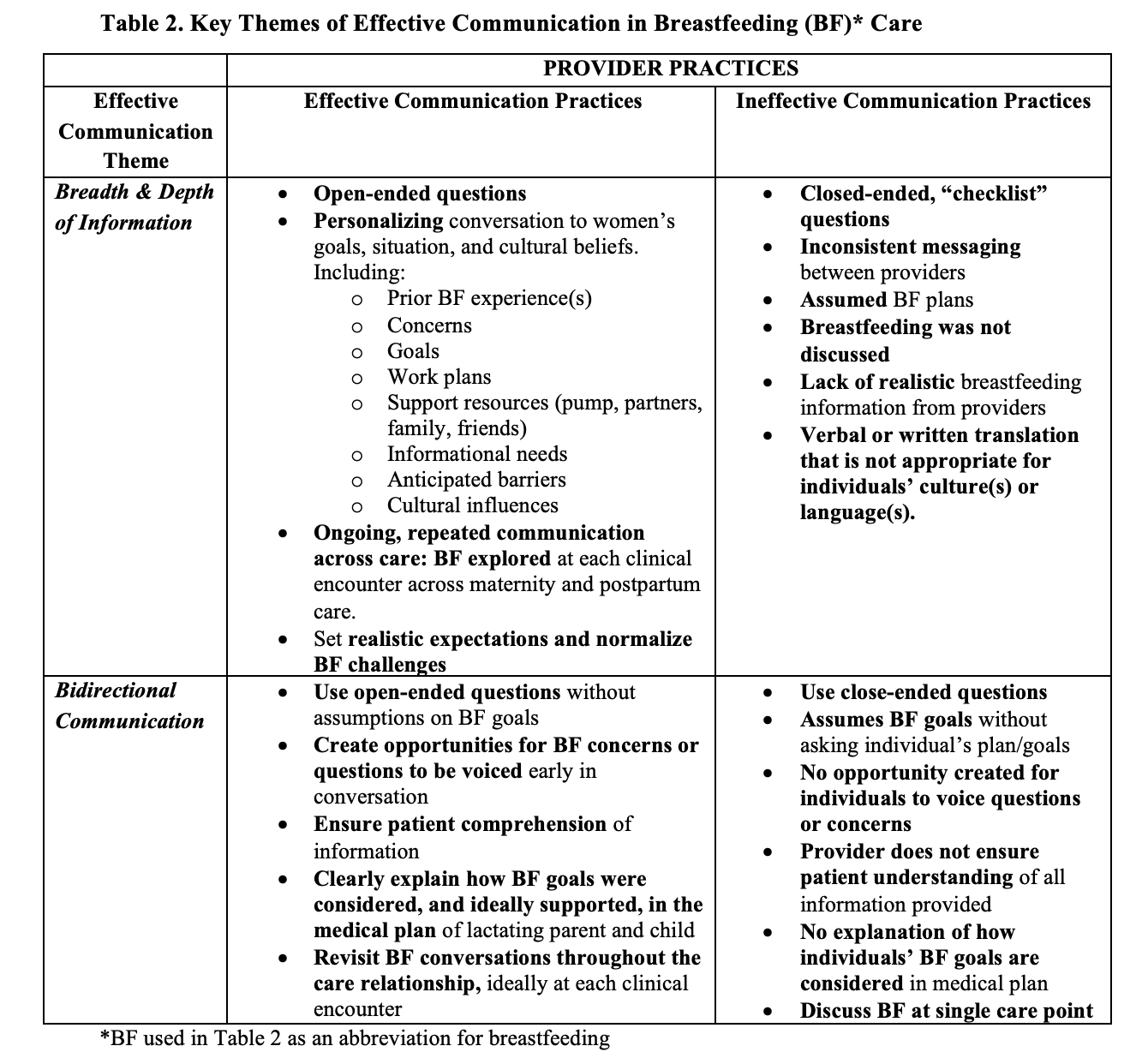

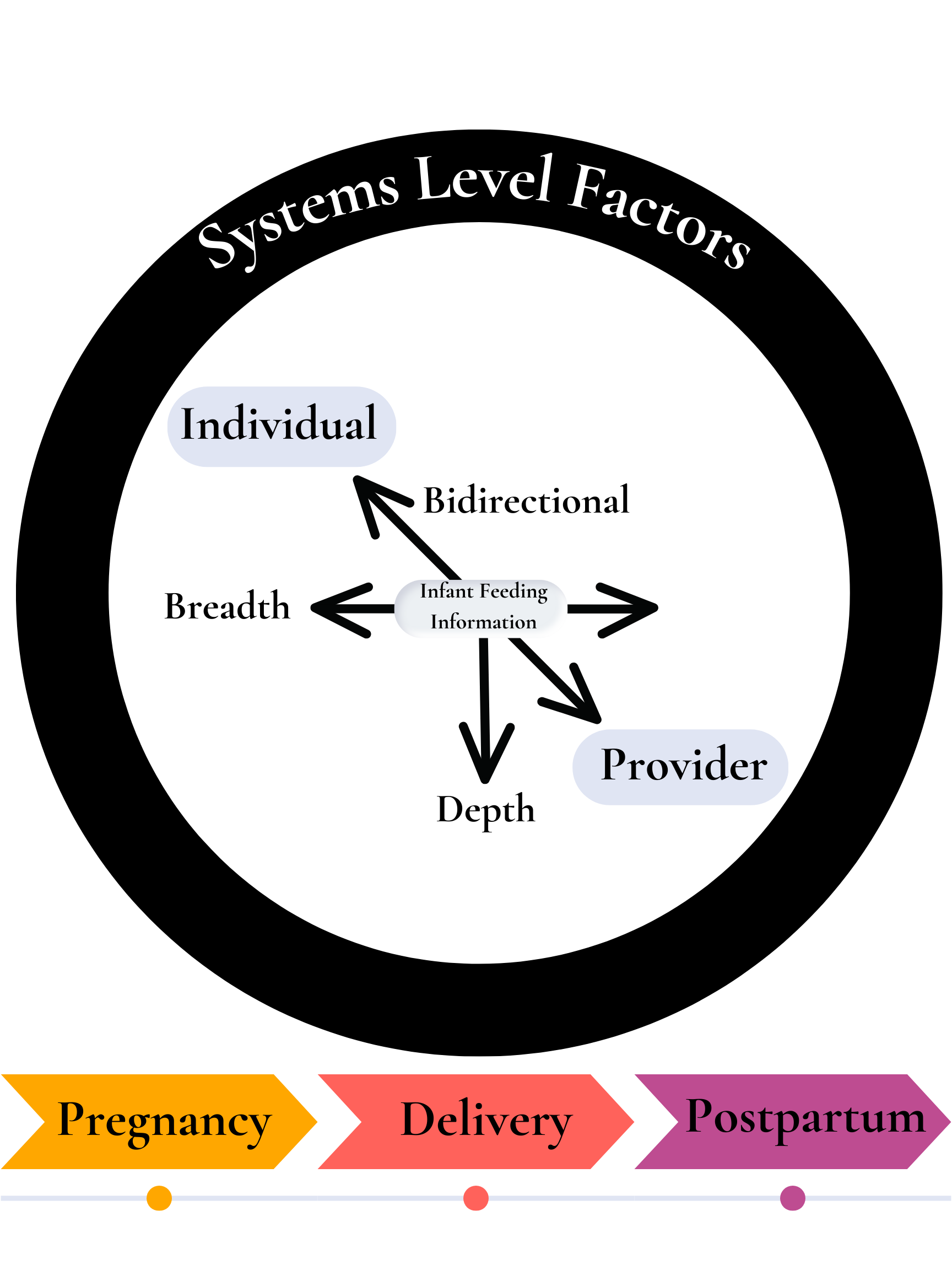

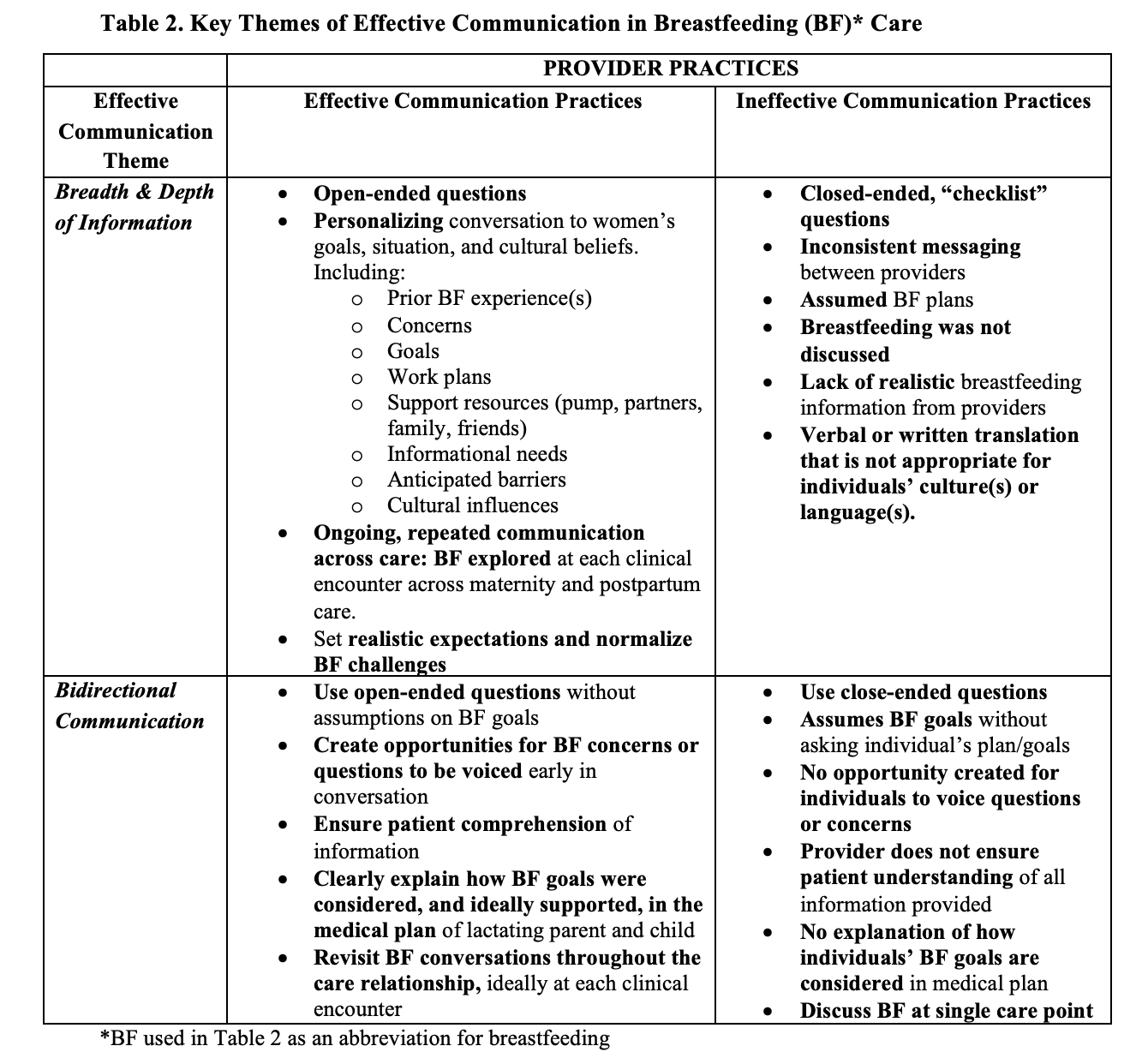

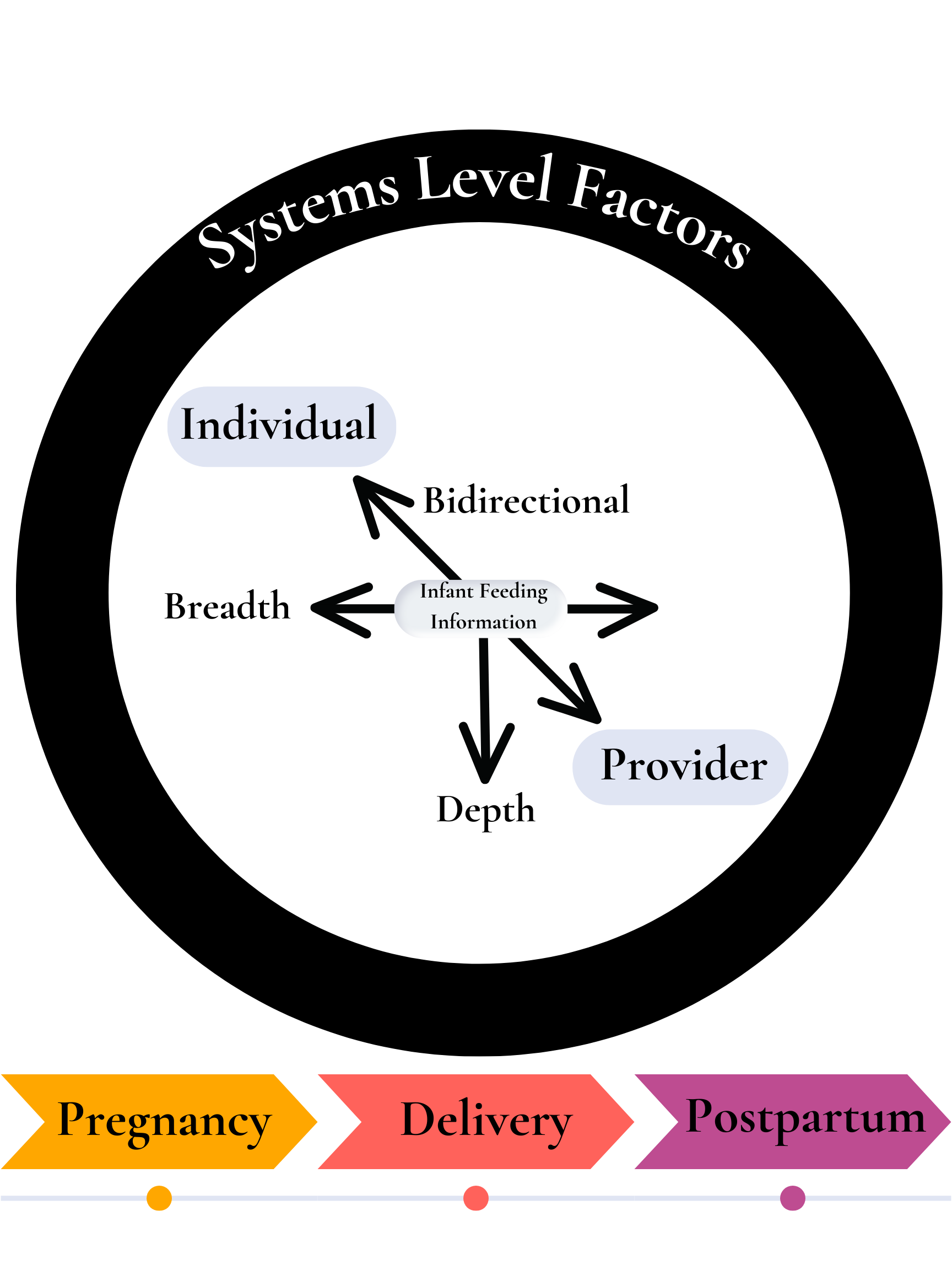

Results: Of the 21 women interviewed, approximately half (48%) were between the ages of 25-31 years and were born outside of the United States (52%) (Table 1). The analysis and resulting “Framework for Effective Communication in Breastfeeding Care” (Fig. 1) identified two themes of effective communication in breastfeeding care, as well as systems level factors that influence them, including provider time, breastfeeding expertise, and language concordance. To Latina women, effective communication consisted of personalized the breadth and depth of breastfeeding information (theme 1) and a bidirectional exchange of information with providers (theme 2). In their view, provider practices that promoted effective communication in breastfeeding care included open-ended questioning that explored women’s prior infant feeding experience, current feeding goals, and expected barriers and supports to reaching these goals across the pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum care continuum. Effective communication was hindered by provider use of rushed, closed-ended, checklist-style questioning on breastfeeding delivered within a single visit (Table 2).

Conclusion(s): Our findings could inform provider and systems level efforts to promote more effective communication in breastfeeding care, ultimately enhancing care quality and person-centeredness.

Table 1. Description of Study Participants, All of Whom Identify as Latina Women

.png)

Framework for Effective Communication in Breastfeeding Care

Table 2. Key Themes of Effective Communication in Breastfeeding (BF) Care

Table 1. Description of Study Participants, All of Whom Identify as Latina Women

.png)

Framework for Effective Communication in Breastfeeding Care

Table 2. Key Themes of Effective Communication in Breastfeeding (BF) Care