Emergency Medicine 4

Session: Emergency Medicine 4

255 - Teaching asthma knowledge in emergencies: a picture-based intervention for caregivers

Saturday, April 26, 2025

2:30pm - 4:45pm HST

Publication Number: 255.6584

Sofia S. Cook, Children's Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States; Meera Patel, California University of Science and Medicine-School of Medicine, Colton, CA, United States; Todd Chang, Children's Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States; Pradip P. Chaudhari, Children's Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States; Anita R. Schmidt, Children's Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States; Natasha Gill, Children's Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Sofia S. Cook, MD (she/her/hers)

Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellow

Children's Hospital Los Angeles

Los Angeles, California, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Asthma affects about 6 million children in the United States, with one sixth requiring annual ED visits. While picture-based asthma action plans (PB-AAPs) improve outpatient caregiver asthma knowledge, their emergency department (ED) utility remains untested.

Objective: Our primary objective was to assess if a low-literacy PB-AAP was superior to the standard written AAP (W-AAP) for improving caregiver knowledge of their child’s asthma management in the ED. Secondary objectives examined factors affecting caregiver asthma knowledge and child asthma symptom control and evaluated knowledge decay and asthma control one month after ED discharge.

Design/Methods: We randomized English- and Spanish-speaking caregivers of children aged 2-17 years with an asthma exacerbation to receive either the PB-AAP (Figure 1) with an educational video or W-AAP with standard nursing education in an urban pediatric ED. We excluded children with complex comorbidities and those admitted to the hospital. We created a novel PB-AAP and asthma knowledge test based on the ED W-AAP and piloted these tools in the ED. We assessed caregiver knowledge at baseline, after ED education, and one month after ED discharge. We used IBM SPSS to run descriptive statistics, t-tests, and multiple linear regression models.

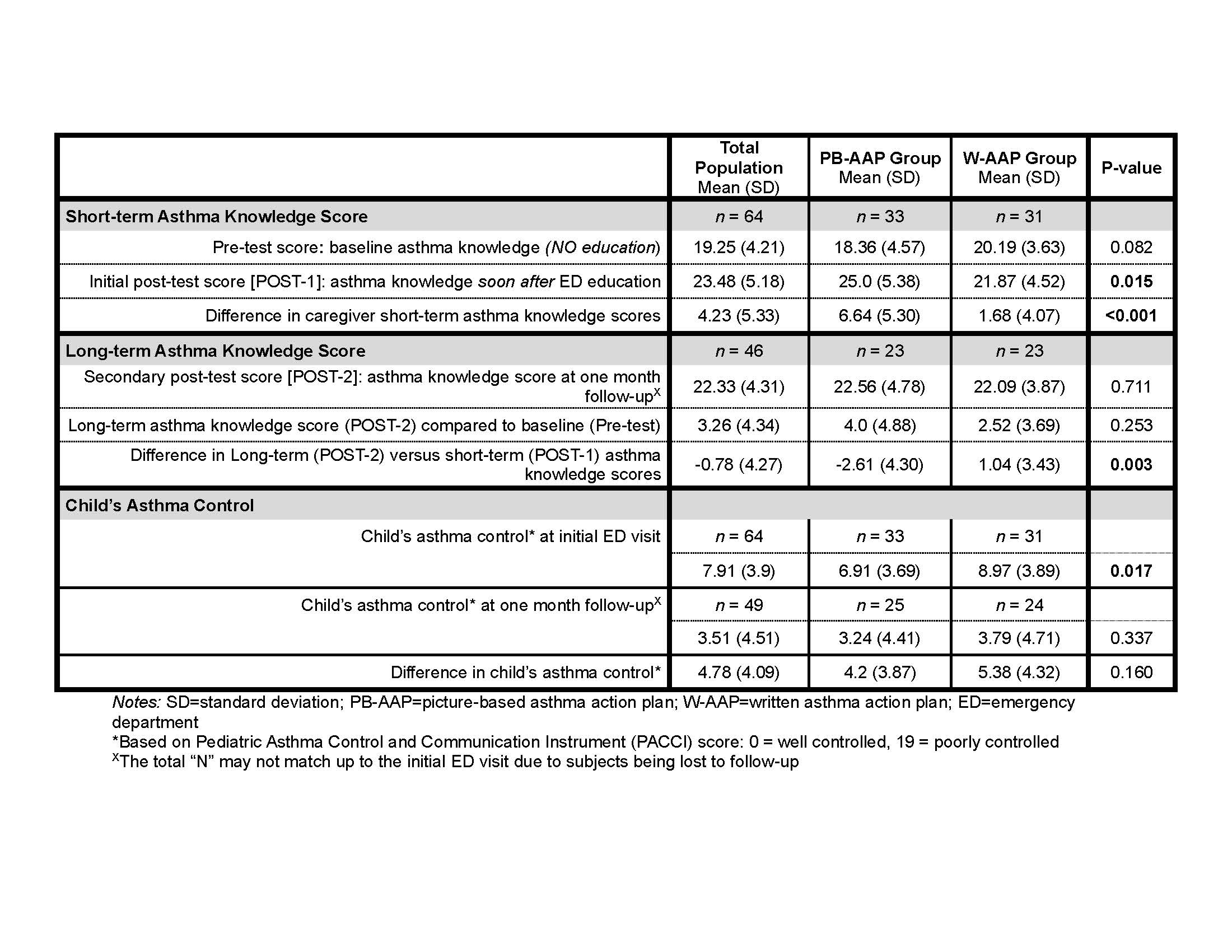

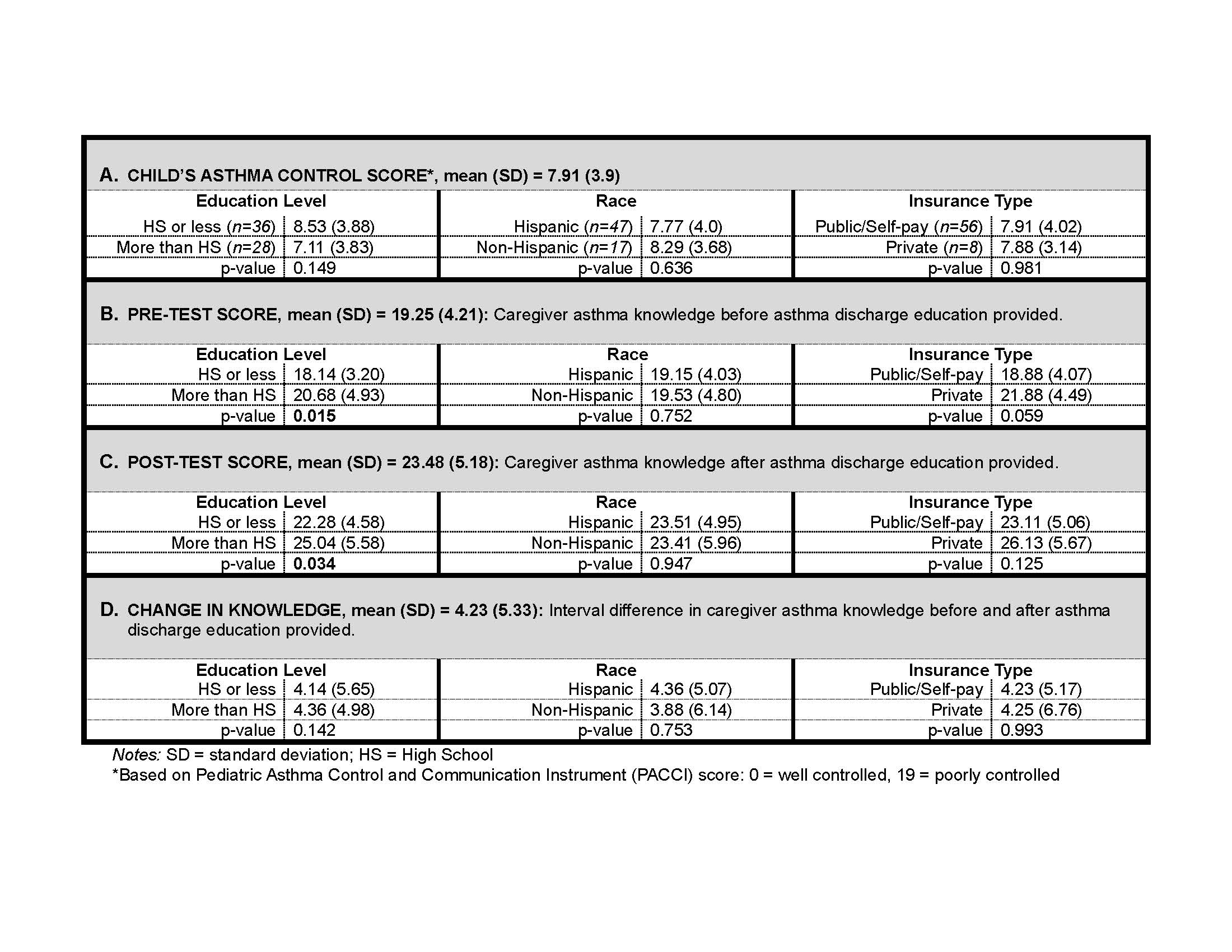

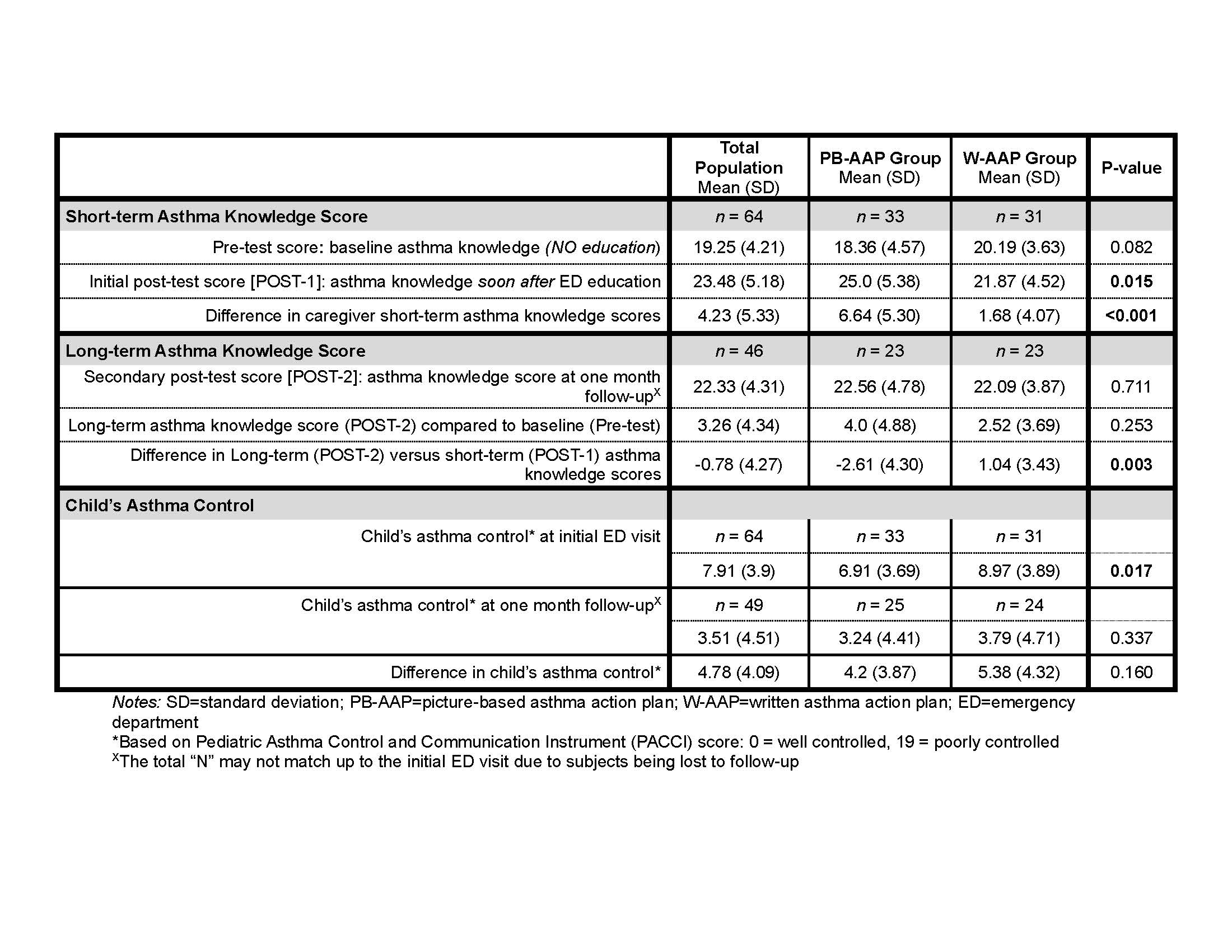

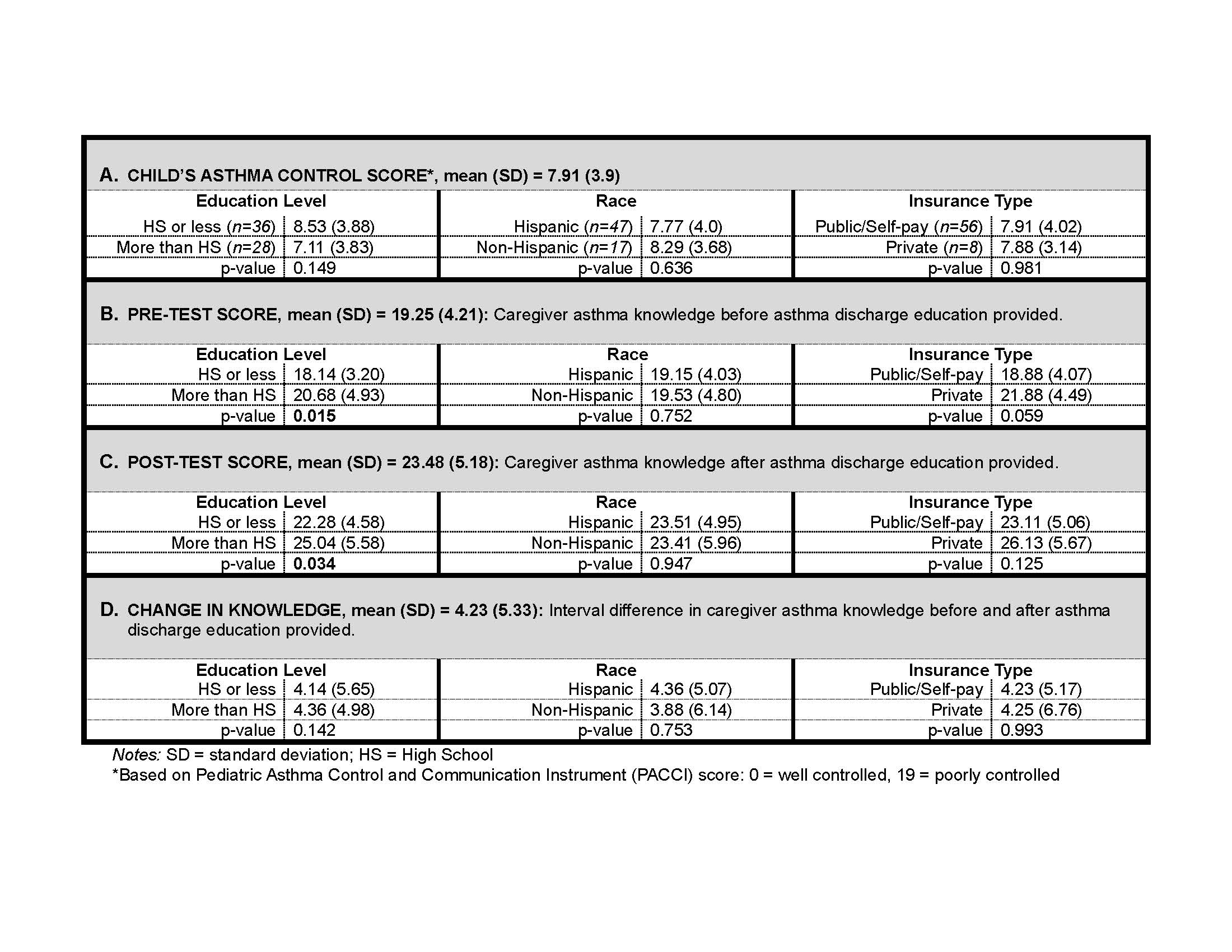

Results: 64 caregivers received either the PB-AAP (n=33) or W-AAP (n=31) and both groups had similar demographics. The PB-AAP is superior to the W-AAP for immediate knowledge gain (Table 1). Caregivers receiving PB-AAPs achieved a significantly higher increase in knowledge scores than those receiving W-AAPs (6.65 vs. 1.68, p< 0.001). However, at one month follow-up, the PB-AAP group showed knowledge decay (-2.61) while W-AAP group scores remained stable (1.04, p=0.003). We identified several predictors of caregiver knowledge. Higher education levels were associated with significantly higher pre-(p=0.015) and post-test scores (p=0.034) (Table 2). Multiple linear regression (p=0.001) yielded that receiving the PB-AAP was the most significant driver of higher post-test performance (p = 0.01). Younger caregiver age (p=0.012), higher education level (p=0.023), and greater health literacy (p=0.047) were also significantly associated with higher post-test scores.

Conclusion(s): A PB-AAP is superior to the standard W-AAP for immediate caregiver knowledge improvement in the ED, though knowledge gains are not sustained long-term. Future research is needed to study how social factors affect health education effectiveness and to ultimately improve asthma knowledge retention.

Figure 1

.jpg) (A) This is an example of a picture-based asthma action plan (PB-AAP) in English for a young child who has no prescriptions for daily asthma preventer medications and requires a spacer with a mask for inhaled medications. (B) This is an example of a PB-AAP in Spanish for an older child who has prescriptions for daily asthma preventer medications and can use a spacer without a mask for inhaled medications. Note: The pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) attending or fellow first complete the W-AAP in the patient’s chart. Based on the W-AAP, a unique version of the PB-AAP in the desired language is created to reflect medication formulations, method of delivery, frequency of use, etc. Medication names and dosages are directly transcribed from the standard AAP onto the PB-AAP. Any medication questions or discrepancies are directly reviewed with the PEM attending and/or fellow.

(A) This is an example of a picture-based asthma action plan (PB-AAP) in English for a young child who has no prescriptions for daily asthma preventer medications and requires a spacer with a mask for inhaled medications. (B) This is an example of a PB-AAP in Spanish for an older child who has prescriptions for daily asthma preventer medications and can use a spacer without a mask for inhaled medications. Note: The pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) attending or fellow first complete the W-AAP in the patient’s chart. Based on the W-AAP, a unique version of the PB-AAP in the desired language is created to reflect medication formulations, method of delivery, frequency of use, etc. Medication names and dosages are directly transcribed from the standard AAP onto the PB-AAP. Any medication questions or discrepancies are directly reviewed with the PEM attending and/or fellow. Table 1

Caregiver’s asthma knowledge scores and child’s asthma control by randomization group

Caregiver’s asthma knowledge scores and child’s asthma control by randomization groupTable 2

Disparities in child’s asthma control and caregiver’s asthma knowledge scores by caregiver’s highest education level, caregiver’s race, and child’s insurance type (N=64)

Disparities in child’s asthma control and caregiver’s asthma knowledge scores by caregiver’s highest education level, caregiver’s race, and child’s insurance type (N=64)Figure 1

.jpg) (A) This is an example of a picture-based asthma action plan (PB-AAP) in English for a young child who has no prescriptions for daily asthma preventer medications and requires a spacer with a mask for inhaled medications. (B) This is an example of a PB-AAP in Spanish for an older child who has prescriptions for daily asthma preventer medications and can use a spacer without a mask for inhaled medications. Note: The pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) attending or fellow first complete the W-AAP in the patient’s chart. Based on the W-AAP, a unique version of the PB-AAP in the desired language is created to reflect medication formulations, method of delivery, frequency of use, etc. Medication names and dosages are directly transcribed from the standard AAP onto the PB-AAP. Any medication questions or discrepancies are directly reviewed with the PEM attending and/or fellow.

(A) This is an example of a picture-based asthma action plan (PB-AAP) in English for a young child who has no prescriptions for daily asthma preventer medications and requires a spacer with a mask for inhaled medications. (B) This is an example of a PB-AAP in Spanish for an older child who has prescriptions for daily asthma preventer medications and can use a spacer without a mask for inhaled medications. Note: The pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) attending or fellow first complete the W-AAP in the patient’s chart. Based on the W-AAP, a unique version of the PB-AAP in the desired language is created to reflect medication formulations, method of delivery, frequency of use, etc. Medication names and dosages are directly transcribed from the standard AAP onto the PB-AAP. Any medication questions or discrepancies are directly reviewed with the PEM attending and/or fellow. Table 1

Caregiver’s asthma knowledge scores and child’s asthma control by randomization group

Caregiver’s asthma knowledge scores and child’s asthma control by randomization groupTable 2

Disparities in child’s asthma control and caregiver’s asthma knowledge scores by caregiver’s highest education level, caregiver’s race, and child’s insurance type (N=64)

Disparities in child’s asthma control and caregiver’s asthma knowledge scores by caregiver’s highest education level, caregiver’s race, and child’s insurance type (N=64)