Children with Chronic Conditions 3

Session: Children with Chronic Conditions 3

460 - Predictors of Low Self-Efficacy Across Healthcare Decision-Making Tasks among Caregivers of Children and Youth with Special Healthcare Needs

Monday, April 28, 2025

7:00am - 9:15am HST

Publication Number: 460.6109

Cameron A. Cooper, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States; Leonardo Barrera, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States; Marie E. Heffernan, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States; Ryan Coller, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI, United States; Carolyn C.. Foster, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

.jpg)

Cameron A. Cooper, MPH (she/her/hers)

Behavioral Research Coordinator III

Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago

Chicago, Illinois, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Our limited understanding of the predictors of caregivers’ self-efficacy (confidence) managing the healthcare of children and youth with special healthcare needs (CYSHCN) prevents the design of interventions to promote it. Although current literature supports that caregiver self-efficacy improves CYSHCN health outcomes, the factors contributing to caregiver self-efficacy when making decisions about healthcare tasks at home are unknown.

Objective: To examine factors that predict low healthcare decision-making self-efficacy in family caregivers of CYSHCN.

Design/Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional national survey of English and Spanish-speaking caregivers of CYSHCN meeting ≥1 CYSHCN screener criteria from 9/2023-12/2023 using a national Qualtrics panel. We administered a validated survey to assess caregiver self-efficacy managing their CYSHCN’s healthcare. The present research focuses on 5 items capturing caregiver self-efficacy specifically for decision-making related to their child’s symptoms or treatments. Lower self-efficacy was defined as responses of ‘not confident’ or ‘somewhat confident.’ Chi-squared tests and multivariable logistic regression were used to examine predictors of lower self-efficacy.

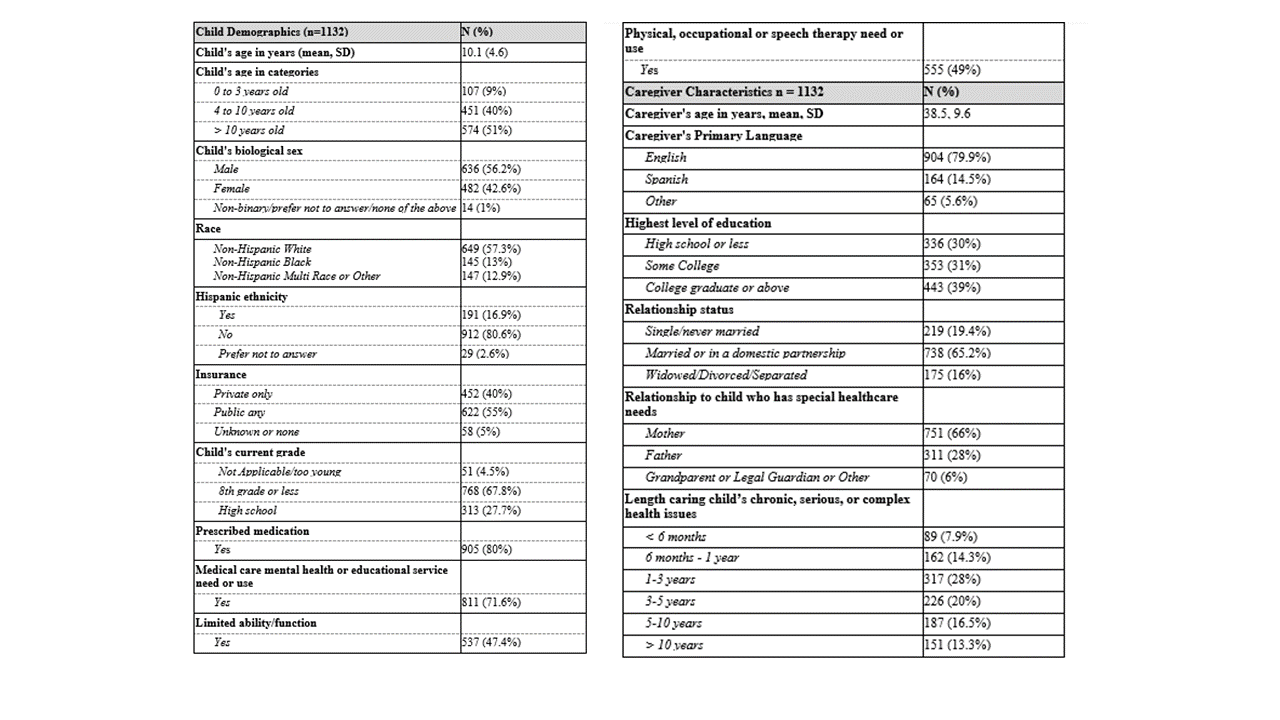

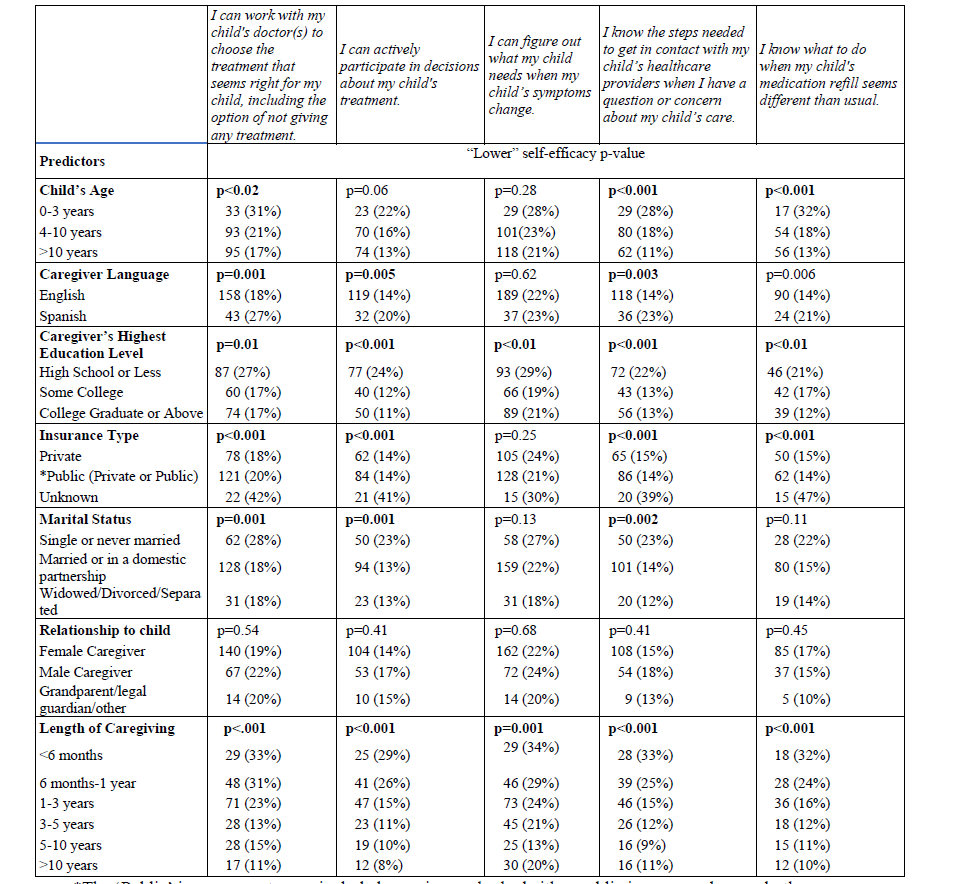

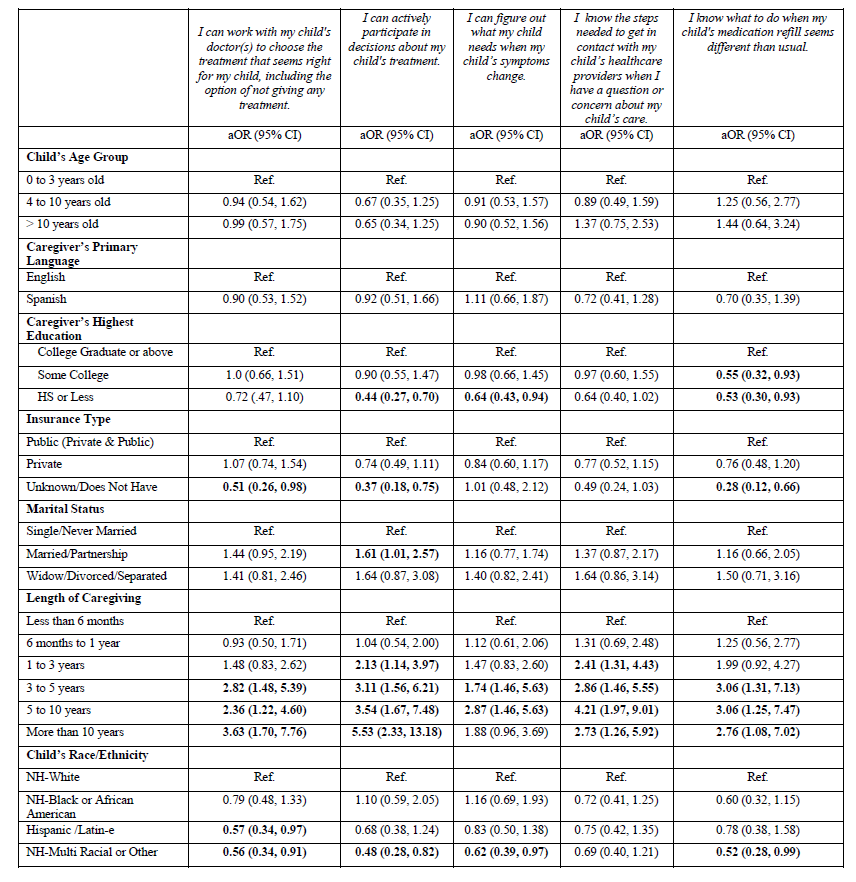

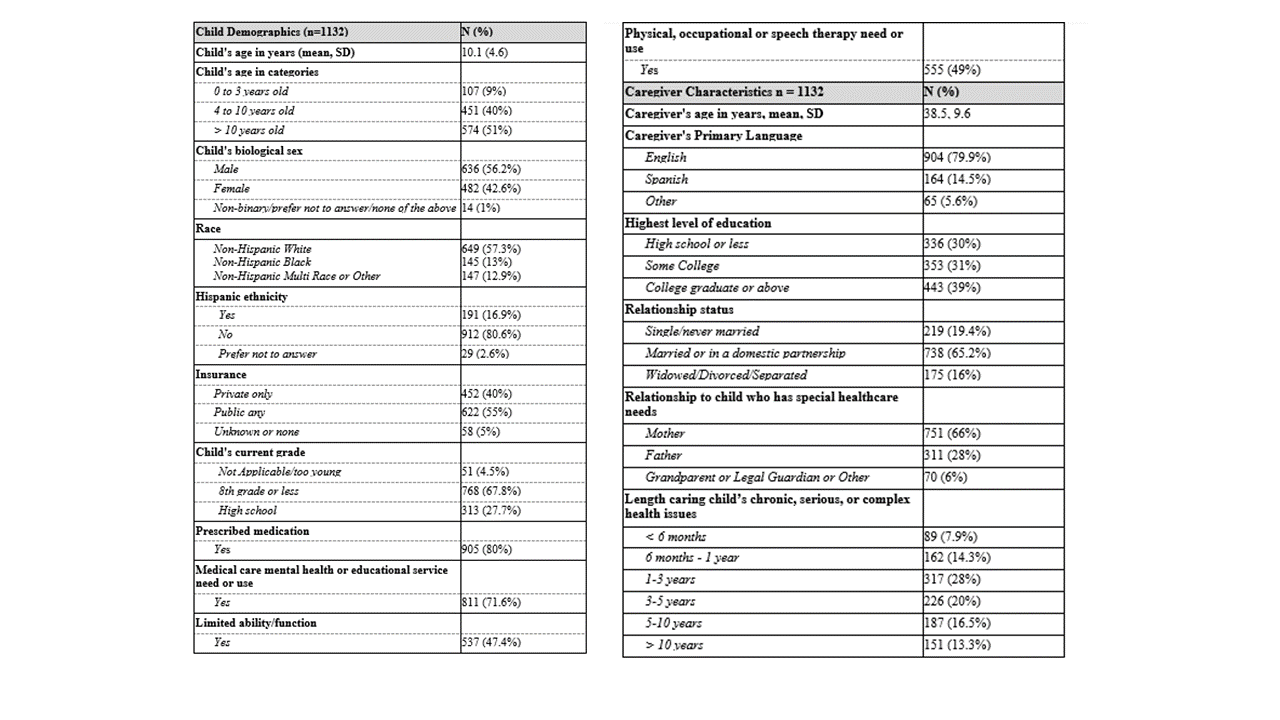

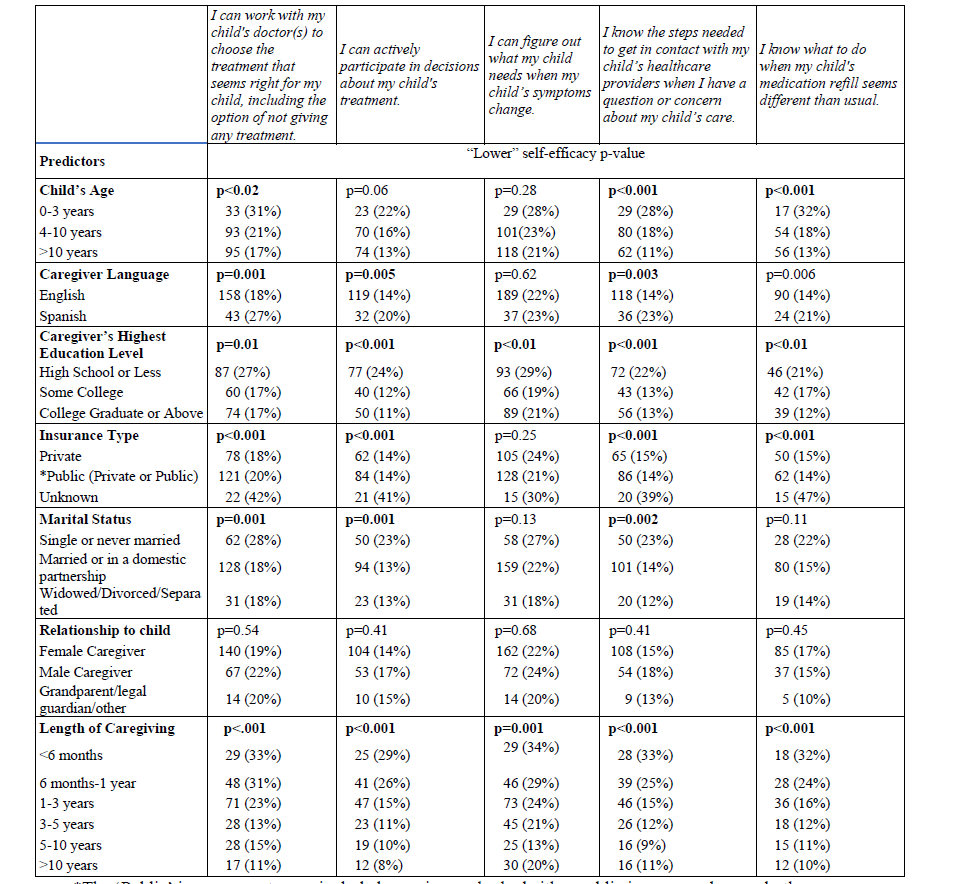

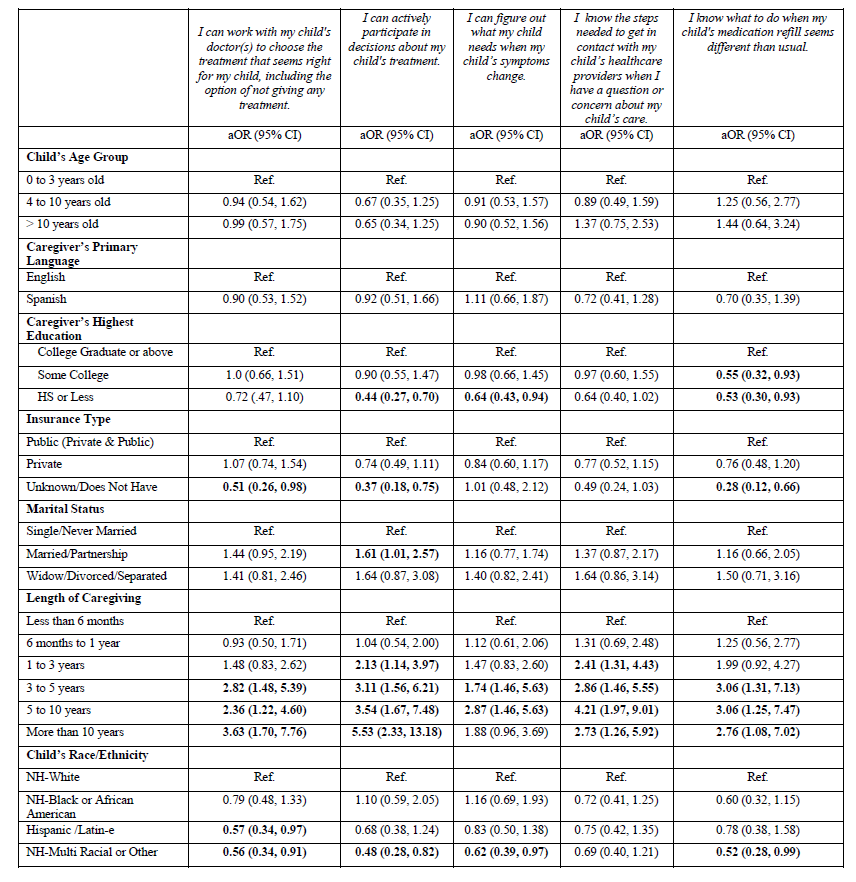

Results: A total of N=1132 caregivers were included in the sample (Table 1). Several predictor variables were significantly associated with self-efficacy in bivariate analyses (Table 2). Multivariable regression revealed that English-speaking caregivers with higher education, married or divorced/widowed status, longer duration of caregiving, and older children, had lower odds of lower self-efficacy across the 5 items [ranging from 0.44 (0.27, 0.70) to 5.53 (2.23, 13.18)], all p< 0.05). Caregivers who reported that their child had no/unknown insurance had higher adjusted odds of lower self-efficacy (vs. any public insurance), but only for three of the five items (Table 3). Caregivers who identified their child as Hispanic/Latine or Multiracial had higher adjusted odds of a lower self-efficacy score on three items compared to those who reported their child as being Non-Hispanic White (Table 3).

Conclusion(s): Our findings suggest that certain factors like insurance status and caregiver education level are associated with a caregiver’s level of self-efficacy in completing decision making tasks related to their child’s health care at home. Future research should aim to determine if caregiver self-efficacy is associated with better execution of healthcare tasks or better child health outcomes. This would help clinicians promote self-efficacy in caregivers and improve home healthcare outcomes for CYSHCN.

Table 1. Child and Caregiver Demographics and Child Clinical Characteristics

Results reported by family caregiver survey respondents. All values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated as mean with standard deviation (SD)

Results reported by family caregiver survey respondents. All values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated as mean with standard deviation (SD)Table 2. Bivariate Comparison of Caregiver Self-Efficacy Managing a Child’s Medications and Treatments and Child and Caregiver Characteristics.

Table 2 shows the bivariate results of child and caregiver characteristics of those who endorsed “lower” self-efficacy (“Not confident or somewhat confident”). All values are n (%) unless otherwise stated. P values <0.05 were considered significant. *The ‘Public’ insurance category included caregivers who had either public insurance alone or both public and private insurance.

Table 2 shows the bivariate results of child and caregiver characteristics of those who endorsed “lower” self-efficacy (“Not confident or somewhat confident”). All values are n (%) unless otherwise stated. P values <0.05 were considered significant. *The ‘Public’ insurance category included caregivers who had either public insurance alone or both public and private insurance.Table 3. Logistic regression analyzing higher odds of endorsing lower self-efficacy across decision making tasks.

*Total n varied for each question based on skip logic. Question 1 n=1043, question 2 n=1041, question 3 n=1037, question 4 n=1032, question 5 n=758.

*Total n varied for each question based on skip logic. Question 1 n=1043, question 2 n=1041, question 3 n=1037, question 4 n=1032, question 5 n=758.Table 1. Child and Caregiver Demographics and Child Clinical Characteristics

Results reported by family caregiver survey respondents. All values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated as mean with standard deviation (SD)

Results reported by family caregiver survey respondents. All values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated as mean with standard deviation (SD)Table 2. Bivariate Comparison of Caregiver Self-Efficacy Managing a Child’s Medications and Treatments and Child and Caregiver Characteristics.

Table 2 shows the bivariate results of child and caregiver characteristics of those who endorsed “lower” self-efficacy (“Not confident or somewhat confident”). All values are n (%) unless otherwise stated. P values <0.05 were considered significant. *The ‘Public’ insurance category included caregivers who had either public insurance alone or both public and private insurance.

Table 2 shows the bivariate results of child and caregiver characteristics of those who endorsed “lower” self-efficacy (“Not confident or somewhat confident”). All values are n (%) unless otherwise stated. P values <0.05 were considered significant. *The ‘Public’ insurance category included caregivers who had either public insurance alone or both public and private insurance.Table 3. Logistic regression analyzing higher odds of endorsing lower self-efficacy across decision making tasks.

*Total n varied for each question based on skip logic. Question 1 n=1043, question 2 n=1041, question 3 n=1037, question 4 n=1032, question 5 n=758.

*Total n varied for each question based on skip logic. Question 1 n=1043, question 2 n=1041, question 3 n=1037, question 4 n=1032, question 5 n=758.