Adolescent Medicine 6: Sexual & Reproductive Health

Session: Adolescent Medicine 6: Sexual & Reproductive Health

149 - A Systematic Review of Adolescent Period Poverty in the United States and Canada

Monday, April 28, 2025

7:00am - 9:15am HST

Publication Number: 149.3614

Julie Samuels, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, United States; Chana Liberow, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, United States; Elizabeth M.. Alderman, The Children's Hospital at Montefiore/Albert Einstein College of Mediicine, New Rochelle, NY, United States; Michael D.. Cabana, Children's Hospital at Montefiore/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, NY, United States

Julie Samuels, BA (she/her/hers)

Medical Student

Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Bronx, New York, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Period poverty is defined as “inadequate access to menstrual hygiene tools and educations, including but not limited to sanitary products, washing facilities, and waste management.” Prior research in low- and middle-income countries has shown that period poverty is associated with poor mental health, low self-esteem, and school absenteeism. Despite global efforts to identify adolescent period poverty and relieve these burdens in low- and middle-income countries, there is limited research regarding the prevalence of period poverty in high income countries.

Objective: To assess the prevalence of period poverty in adolescent populations in the United States (US) and Canada.

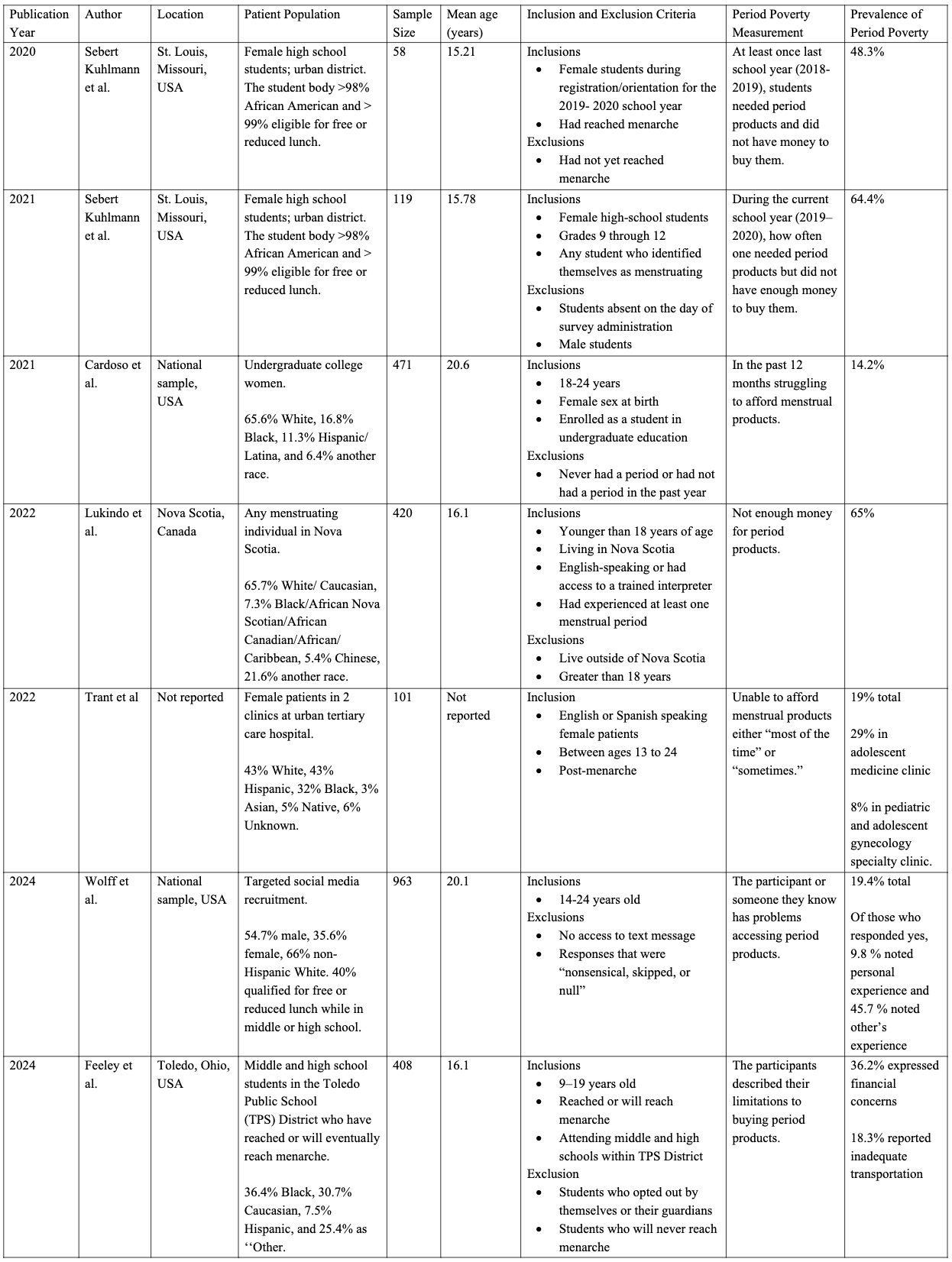

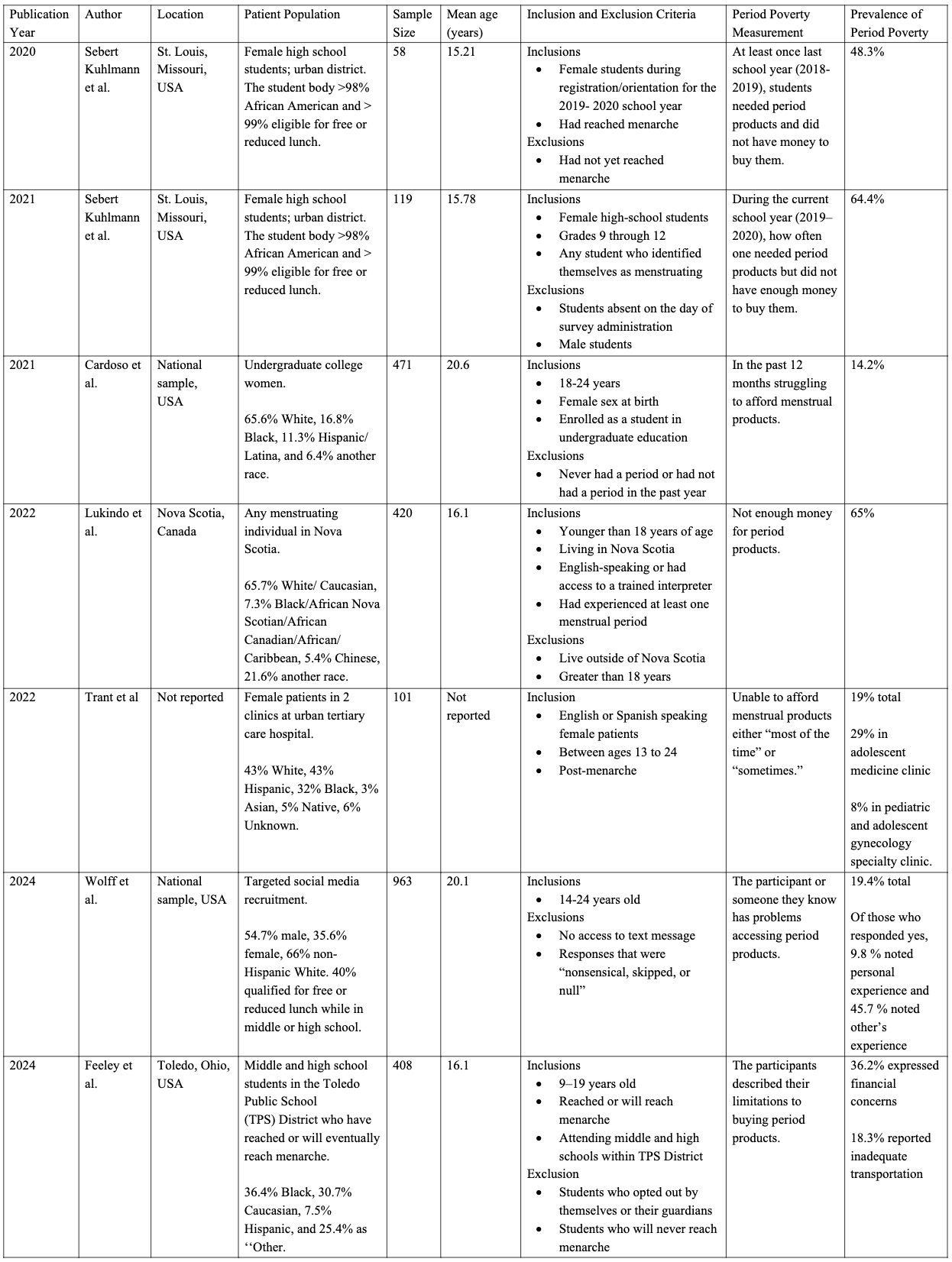

Design/Methods: We conducted a systematic review of the literature to identify all published articles describing the prevalence of adolescent period poverty within the US and Canada as well as interventions developed to address this issue. We searched for English-language articles in PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Library from 1/1/2000 through 7/1/2024. Studies with participants from menarche to age 26 were included. Two investigators examined abstracts of publications to identify applicable studies. The full texts of eligible articles were independently reviewed for inclusion. Discordance was resolved by consensus of both investigators and, if necessary, adjudicated by a third investigator. We abstracted author, year, location, patient population, sample size, mean age, inclusion/exclusion criteria, period poverty definition, and prevalence. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the results.

Results: Of 1576 unique articles identified, 102 were screened for full text review, and 7 were included in data extraction and analysis. The Cohen’s kappa was 0.61. Period poverty definitions varied across all 7 studies; the majority addressed affordability of products. The prevalence of period poverty ranged from 9% to 65% (Table 1). No studies described interventions to address period poverty.

Conclusion(s): The studies in our analysis identified a wide range of the prevalence of adolescent period poverty in a variety of settings. In addition, there were no controlled trials of interventions. There is a need for interventions to reduce adolescent period poverty in the US and Canada. Furthermore, additional research should assess themes beyond affordability of products, including transportation and access to washing facilities. The prevalence of period poverty in these studies indicate that clinicians should screen for period poverty when obtaining a menstrual history in adolescents, adding to social determinants of health screening.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.