Emergency Medicine 12

Session: Emergency Medicine 12

540 - Evaluating Acute and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders among Children Who Experience Traumatic Injuries

Monday, April 28, 2025

7:00am - 9:15am HST

Publication Number: 540.4623

Shea Lammers, Children's Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States; Laura Plasencia, Children's Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States; Kati Kiely, Children's Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota, mpls, MN, United States; Kate Koehn, Children's Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States; Kelly R.. Bergmann, Children’s Minnesota, University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital, Minneapolis, MN, United States; Henry Ortega, Children's Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States

Shea M. Lammers, MS (she/her/hers)

Statistician I

Children's Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota

Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Families with injured children experiencing acute or post-traumatic stress often require mental health resources. Research on screening methods that accurately identify traumatic stress symptoms in children in the emergent setting is limited.

Objective: We aimed to compare the selected screening tools, assess whether demographic or traumatic injury factors were associated with positive screenings, and examine perceived helpfulness of the screening tools.

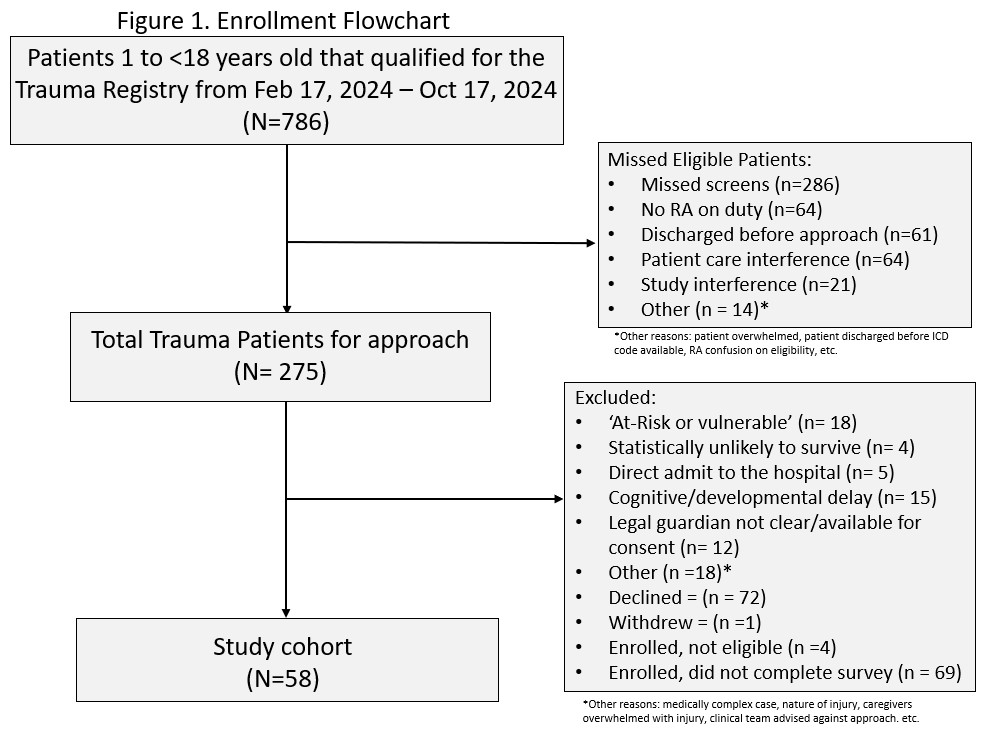

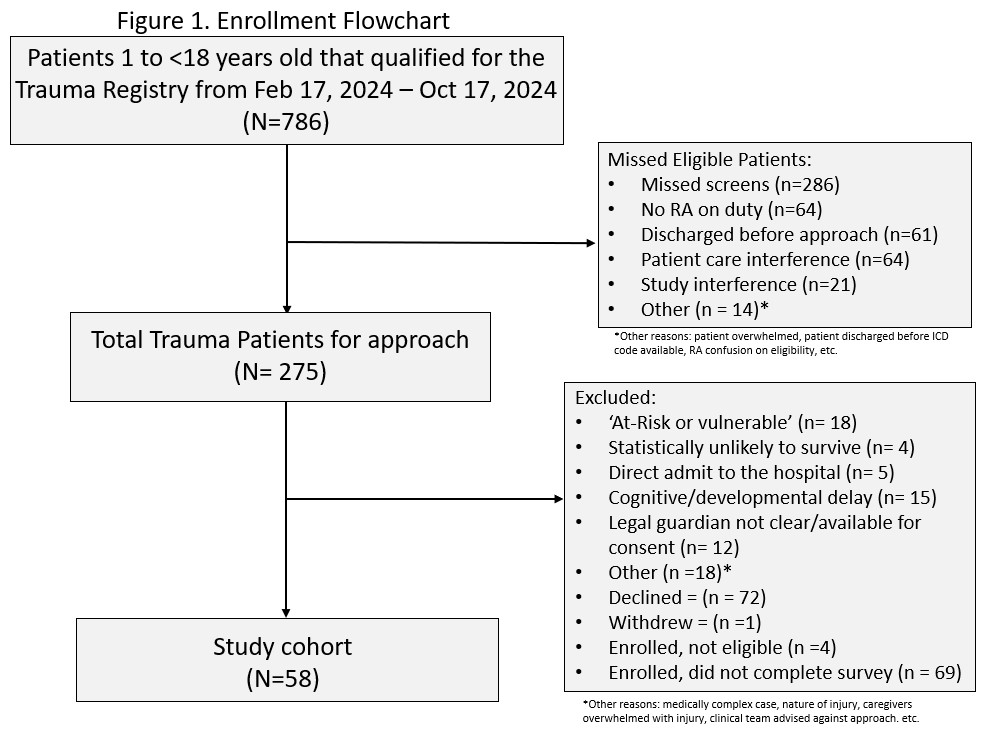

Design/Methods: We conducted a prospective, cross-sectional cohort study of children and adolescents (ages 1-17 years) who presented with a traumatic injury. Children were excluded if they were: considered ‘at-risk or vulnerable,’ or legal guardianship was unclear, among other reasons (Figure 1). Children ages 1-5 years had a caregiver fill out the Young Child PTSD Screen (YCPS), while children ages 6-17 were given a self-report Acute Stress Checklist-6 (ACS-6). Both screeners were distributed a minimum of 24 hours after injury with completion required by day 30 post-injury. Enrollment took place from February to October 2024. Parametric or nonparametric tests were used after assessing for normality. Chi squares, Fisher’s Exact tests, or one-way ANOVAs were utilized to determine differences between groups. Bonferroni corrections were applied to multiple comparisons. Significance tests were omitted if cell counts were low.

Results: Of 786 patients who presented with a traumatic injury, we identified 275 approachable children (Figure 1). Of these, we enrolled 131 children (48%), and 58 completed the surveys (21%). Descriptive statistics conveyed patient characteristics across screening outcomes (Table 1). There were significantly more positive screens in the YCPS group than the ASC-6 group (p < 0.01). Children in the YCPS group with a positive trauma screen had significantly younger caregivers than other groups, (Table 1; p =0.01). There was a significant difference in caregiver age between the YCPS positive and ASC-6 negative groups (p < 0.01). Positive screening patients perceived the trauma screeners as significantly more helpful than negative screening patients (p <.05). There were no significant differences between trauma screener outcome and patient sex, insurance type, income level, or caregiver education (Table 1).

Conclusion(s): Younger caregivers with younger children are more likely to screen positive for acute traumatic stress. Patients screening positive for traumatic stress are more likely to perceive the screeners as helpful. Traumatic stress symptoms persist across demographic variables, injury types, and severity, which warrants further study.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics by Trauma Screener

.jpg) Notes. * Indicates a Fisher’s Exact Test; ^ Indicates a one-way ANOVA; Neg = Negative; Pos = Positive; IQR = Interquartile range; SD = Standard deviation; Other injuries include: fell off of scooter, trampoline, kicked by a horse, wrapping was too tight, fracture while playing with parent; There is one remarried caregiver in YCPS neg group; There is one ‘other’ education in the YCPS pos group; Income level n = 53; Perceived Helpfulness n =59.

Notes. * Indicates a Fisher’s Exact Test; ^ Indicates a one-way ANOVA; Neg = Negative; Pos = Positive; IQR = Interquartile range; SD = Standard deviation; Other injuries include: fell off of scooter, trampoline, kicked by a horse, wrapping was too tight, fracture while playing with parent; There is one remarried caregiver in YCPS neg group; There is one ‘other’ education in the YCPS pos group; Income level n = 53; Perceived Helpfulness n =59.Enrollment Flowchart

Table 1. Patient Characteristics by Trauma Screener

.jpg) Notes. * Indicates a Fisher’s Exact Test; ^ Indicates a one-way ANOVA; Neg = Negative; Pos = Positive; IQR = Interquartile range; SD = Standard deviation; Other injuries include: fell off of scooter, trampoline, kicked by a horse, wrapping was too tight, fracture while playing with parent; There is one remarried caregiver in YCPS neg group; There is one ‘other’ education in the YCPS pos group; Income level n = 53; Perceived Helpfulness n =59.

Notes. * Indicates a Fisher’s Exact Test; ^ Indicates a one-way ANOVA; Neg = Negative; Pos = Positive; IQR = Interquartile range; SD = Standard deviation; Other injuries include: fell off of scooter, trampoline, kicked by a horse, wrapping was too tight, fracture while playing with parent; There is one remarried caregiver in YCPS neg group; There is one ‘other’ education in the YCPS pos group; Income level n = 53; Perceived Helpfulness n =59.Enrollment Flowchart