Children with Chronic Conditions 3

Session: Children with Chronic Conditions 3

454 - A Medical Home is Essential to Quality of Life for CYSHCN, but Poorly Measured by Existing Quality of Life Surveys

Monday, April 28, 2025

7:00am - 9:15am HST

Publication Number: 454.3791

Christopher Stille, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, United States; Margaret Comeau, Boston University School of Social Work, Milton, DE, United States; Steph Lomangino, Family Voices, Bloomfield, CT, United States; Hannah Friedman, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, United States; Bethlyn Houlihan, Center for Innovation in Social Work & Health, BUSSW, Boston, MA, United States; Kirk Bjella, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT, United States; Isabel K. Taylor, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT, United States; Stefanie G. Ames, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT, United States

- CS

Christopher Stille, MD, MPH (he/him/his)

Professor and Section Head, General Academic Pediatrics

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Aurora, Colorado, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Families of children and youth with special health care needs (CYSHCN) and especially those with medical complexity (CMC) consider the experience of care within a well-functioning family-centered medical home (FCMH) as an essential determinant of their child’s quality of life (QoL). Current QoL measures are widely felt not to include FCMH in their scope, but few objective data exist.

Objective: To assess the state of measurement of stakeholder-perceived FCMH elements by existing QoL and related measures.

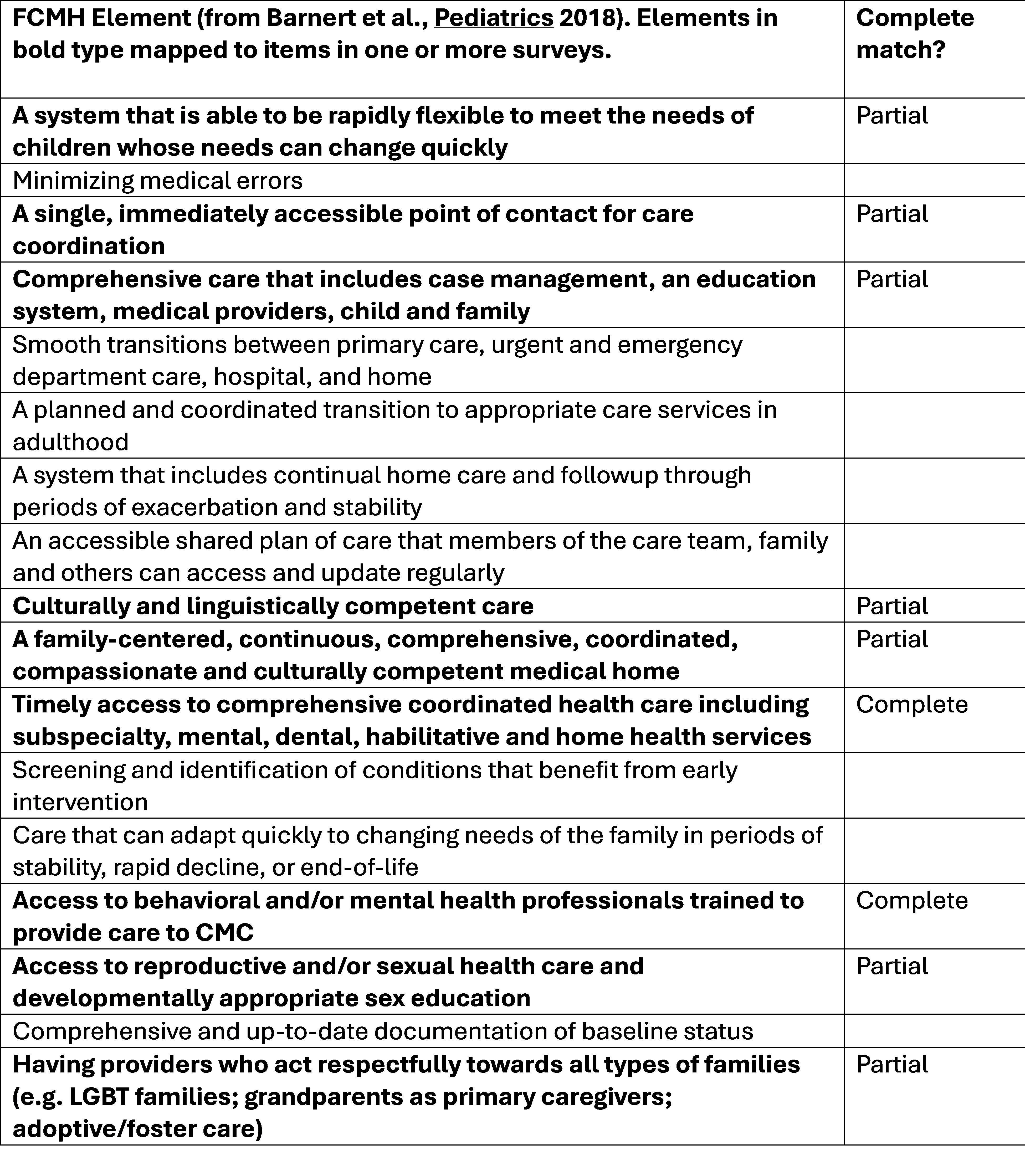

Design/Methods: QoL measures developed and/or validated in CYSHCN were collected in a scoping review, and related measures from the “gray literature” and known measure compendia were added. All were patient or parent surveys. Within the surveys obtainable through Web searching and author contact, each survey item was mapped against 17 elements of the FCMH identified by families and other stakeholders as “elements of a healthy life for children with medical complexity” through group concept mapping from published literature (Barnert et al., Pediatrics 2018). Mapping was done by two reviewers, with disagreements reconciled through discussion. Survey items could map to multiple elements. Fit was described as “complete” (item described the element exactly), “partial” (item described the element but required some revision to map exactly), or none.

Results: 33 surveys were available for review, comprising 989 items. Only two surveys had items mapping to one or more FCMH elements; the KID-KINDL with one item mapping to one element (partial fit), and the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) with 8 items mapping to 8 elements (2 complete fit, 6 partial fit). 8 elements of the MH had no survey items in any surveys that mapped to them [Table].

Conclusion(s): Despite a large number of existing QoL surveys, they describe essential FCMH elements poorly, with only two of 17 elements described completely. However, while not strictly a QoL survey, the NSCH described several elements of the FCMH felt by youth, families and other stakeholders to be critical drivers of QoL for CYSHCN. Substantial measure adaptation and/or development is needed to focus on key determinants of QoL for this population, and should focus more broadly on elements felt to be important by families.

Elements of the Medical Home domain and mapping to existing quality of life and related measures.