Adolescent Medicine 6: Sexual & Reproductive Health

Session: Adolescent Medicine 6: Sexual & Reproductive Health

159 - Parent perceptions about health care professionals as sex educators

Monday, April 28, 2025

7:00am - 9:15am HST

Publication Number: 159.5583

Marla Eisenberg, University of Minnesota Medical School, MINNEAPOLIS, MN, United States; Christopher Mehus, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN, United States; Jill Farris, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN, United States; Shari Plowman, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, MN, United States; Renee Sieving, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States

Marla Eisenberg, ScD, MPH (she/her/hers)

Professor

University of Minnesota Medical School

MINNEAPOLIS, Minnesota, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Adolescents obtain sexual health information from a variety of sources, many of which are not medically accurate. Health care professionals (HCPs) are positioned to offer sexual health information to their adolescent patients and parents. However, HCPs may have concerns about negative parental reactions when they introduce sexual topics, a potential barrier to initiating these conversations. Prior research has shown that parents themselves desire this information from their adolescents’ HCPs.

Objective: The current study examines whether parents perceive HCPs to be an important source of sexual health information for their adolescent children, and how perceptions differ across social identities.

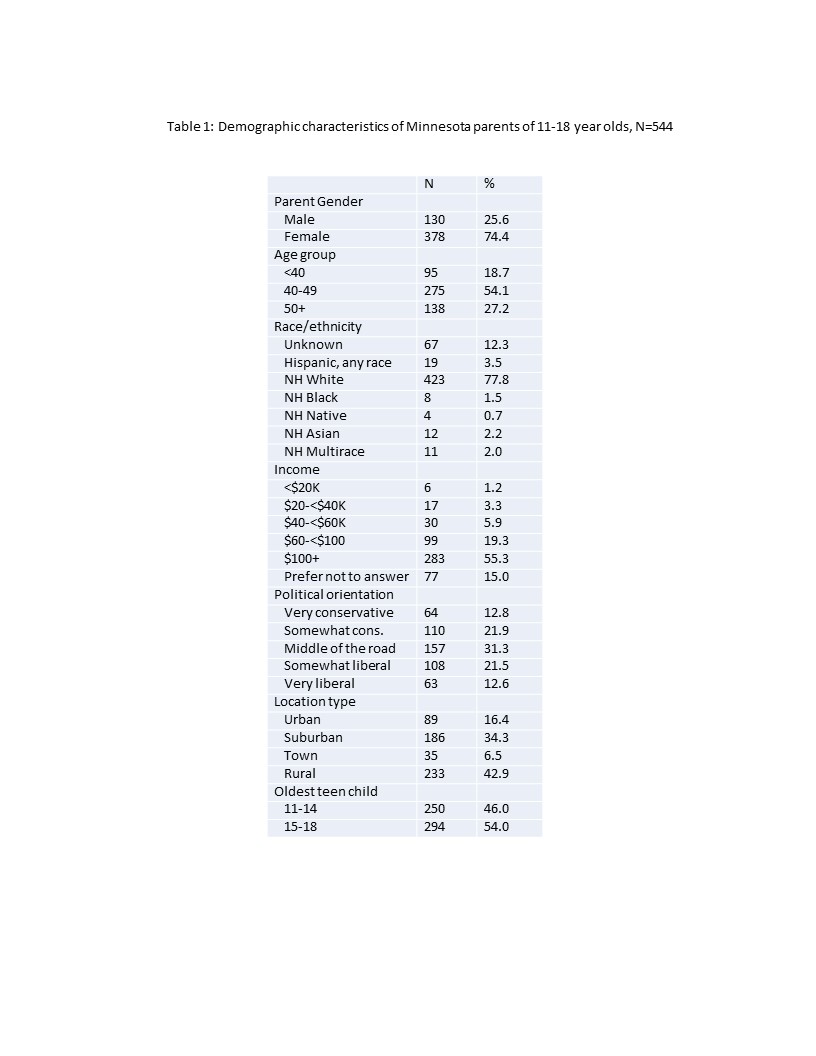

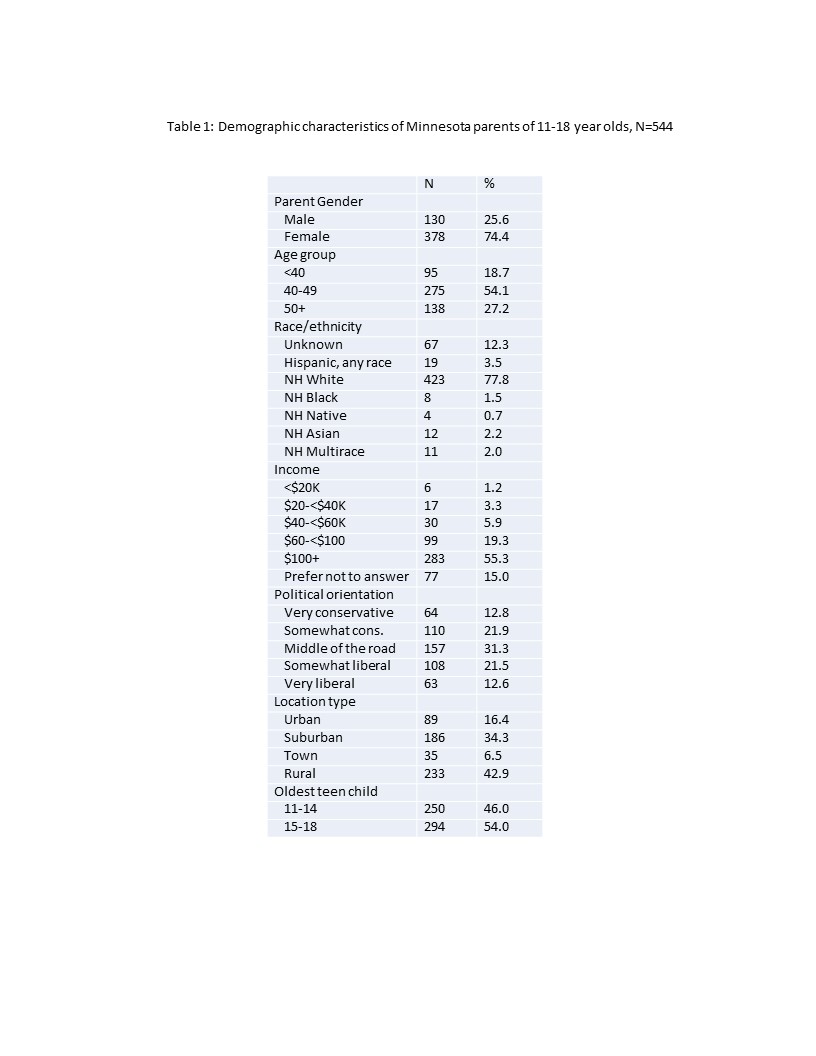

Design/Methods: Survey data were collected in 2021 from a convenience sample of 544 parents of 11-18 year olds in Minnesota. The sample was predominantly female (74%), 40-49 years (54%), and non-Hispanic White (78%) with a range of political views, metropolitan and non-metropolitan locations, and child ages represented (Table 1). Descriptive analyses examined two survey items: “Where do you think young people [get/should get] most of their information about sex and sexuality?” Chi-square tests were used to identify differences in perceptions about HCPs as a source of sexual health information across demographic and social identities.

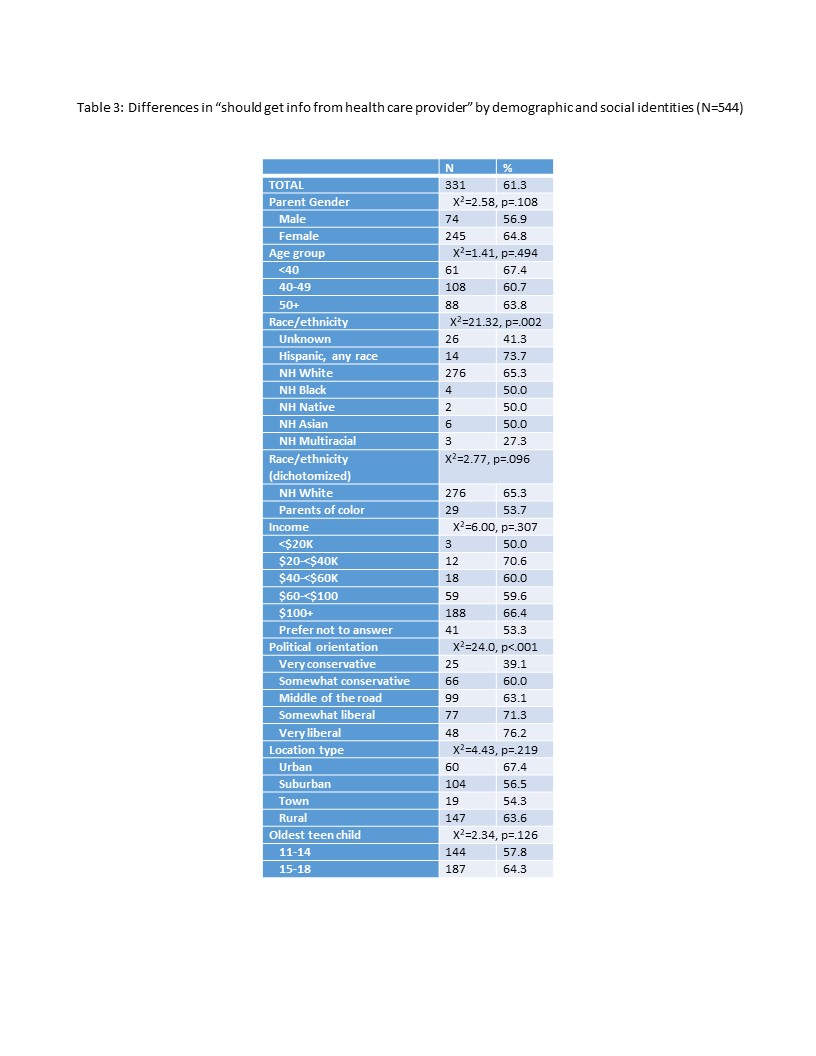

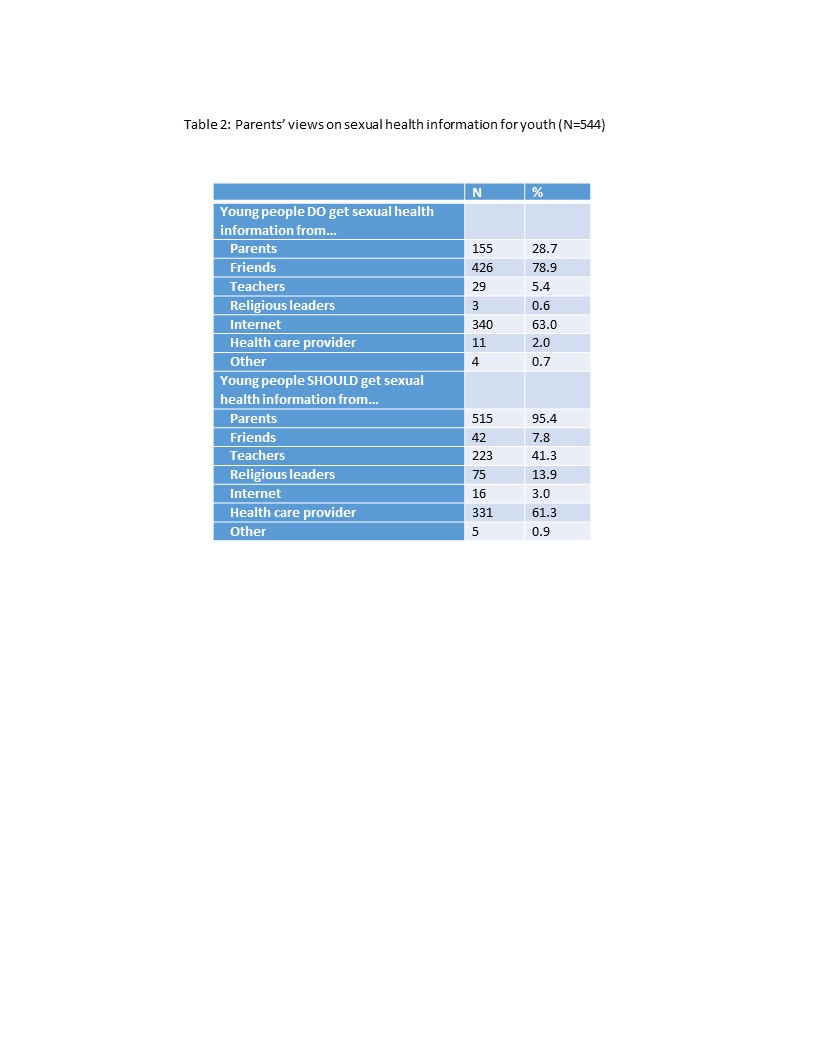

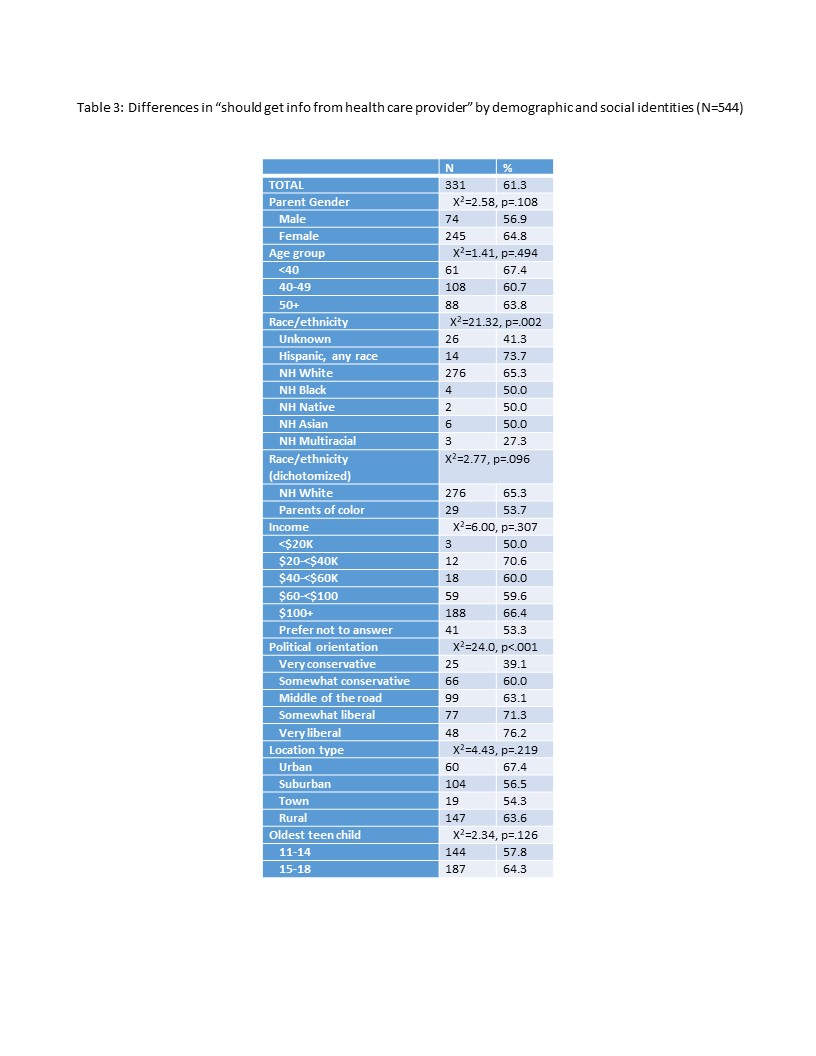

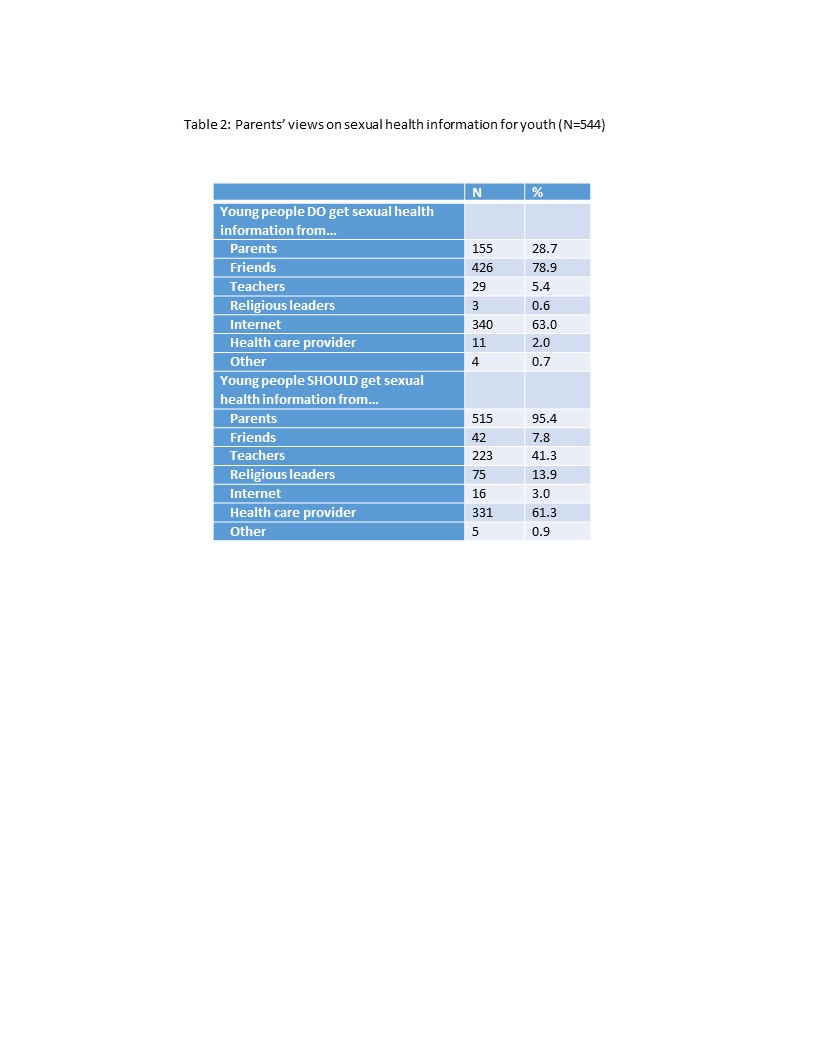

Results: Most parents believed that young people obtained information from friends and the internet, with only 2.0% reporting HCPs as a source of sexual health information (Table 2). In contrast, 61.3% of parents thought young people *should* get sexual health information from a HCP (second only to parents as a preferred source). This opinion did not differ statistically across parent gender, age, income bracket, location type, or age of oldest adolescent child, with a majority in almost all demographic categories indicating support for HCPs as sources of sexual health information (Table 3). Support was significantly lower among parents who described themselves as very conservative politically (39.1%, vs. 60.0-76.2% of more politically liberal parents).

Conclusion(s): This study finds broad parental support for HCPs as a source of sexual health information for young people; framing around health promotion may further influence acceptability across the political spectrum. Because parents and professionals are the most desired sources of information, clinicians should offer sexual health information and guidance to their adolescent patients, and can also share health information and strategies with parents to support them in their role as sexuality educators for their adolescent children.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of Minnesota parents of 11-18 year olds, N=544

Table 2: Parents’ views on sexual health information for youth (N=544)

Table 3: Differences in “should get info from health care provider” by demographic and social identities (N=544)

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of Minnesota parents of 11-18 year olds, N=544

Table 2: Parents’ views on sexual health information for youth (N=544)

Table 3: Differences in “should get info from health care provider” by demographic and social identities (N=544)