Cardiology 2

Session: Cardiology 2

157 - Point of Care Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring for Improved Hypertension Diagnosis in Youth

Friday, April 25, 2025

5:30pm - 7:45pm HST

Publication Number: 157.6120

Carissa M. Baker-Smith, Nemours Children's Hospital, Ellicott City, MD, United States; Carol Prospero, Nemours Children's Hospital, Wilmington, DE, United States; Hal charles. Byck, NemoursAlfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, DE, United States; Bridgette Hindt, Nemours Children's Hospital, Wilmington, DE, United States; Megan E. Keeth, Nemours Children's Hospital, Wilmington, DE, United States; Jorge Gilces Velasquez, Nemours Children's Hospital, Wilington, DE, United States; Kelly Hussong, NemoursAlfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, DE, United States; Erica Sood, Nemours Children's Hospital, Wilmington, DE, United States

Carissa M. BakerSmith, MD MPH (she/her/hers)

Director of Pediatric Preventive Cardiology

Nemours Children's Hospital

Ellicott City, Maryland, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Hypertension (HTN) accounts for 50% of cardiovascular disease in the US. However, distinguishing elevated in-office blood pressure (BP) (white-coat effect/WCE) from persistently elevated BPs (HTN) in youth can be challenging for primary care providers. Current AAP guidelines recommend an average of 3 in-office manual BPs for diagnosing HTN. However, less than 50% of youth follow up for repeat in-office BP assessment or attend subspecialist referral visits for BP evaluation. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM)-an oscillometric BP measurement device worn on the arm for 24 hours- is the gold standard for confirming a diagnosis of HTN. We hypothesize that ABPM in the primary care setting (“point of care”) is accepted, tolerated, and feasible for distinguishing youth with WCE from youth with HTN.

Objective: To assess acceptance, tolerance, and feasibility of point-of-care ABPM for pediatric HTN diagnosis.

Design/Methods: Youth 10 to 17 years of age, with at least one manual in-office BP greater than or equal to the 95th%ile, were offered ‘point of care” ABPM. We utilized a community-engaged mixed-methods approach to assess “point of care” ABPM acceptance by patients, parents, and providers. We assessed patient tolerance using a 5-point Likert scale (1=poor to 5=excellent). We assessed feasibility based on ABPM availability and acceptance. We quantitatively correlated HTN diagnosis based on repeat in-office BP with HTN diagnosis based on ABPM.

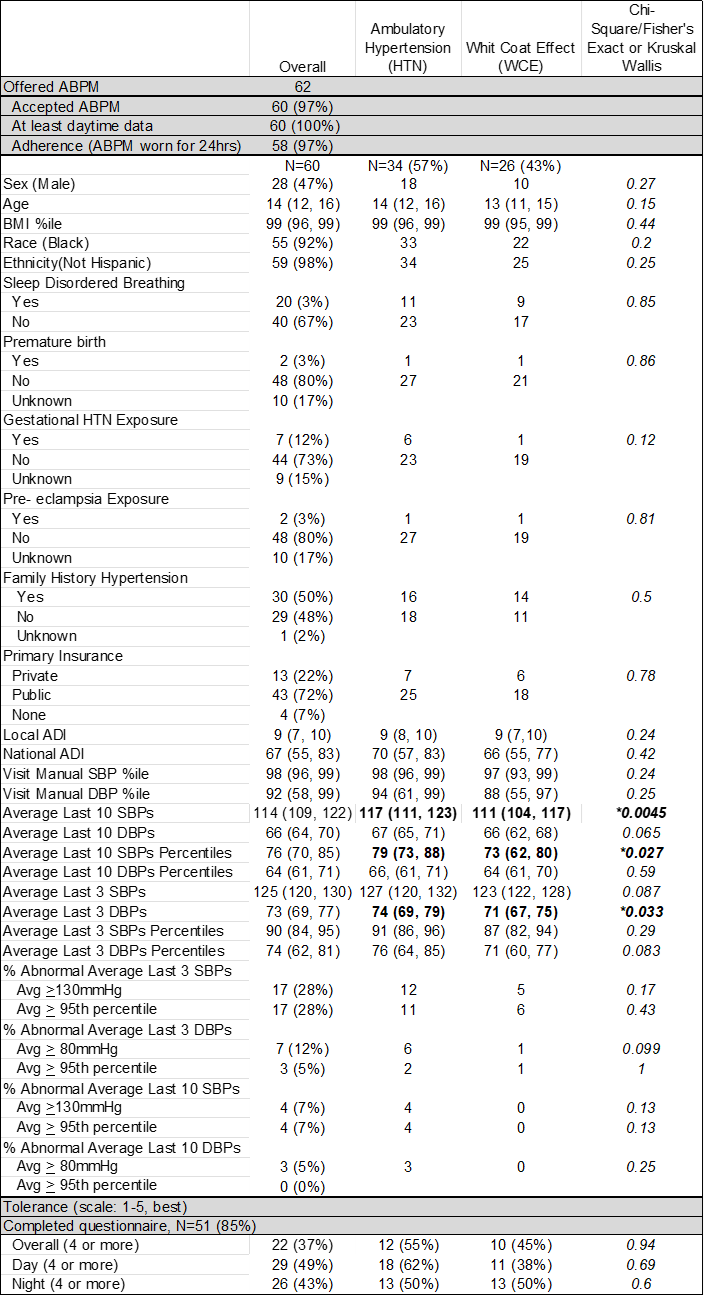

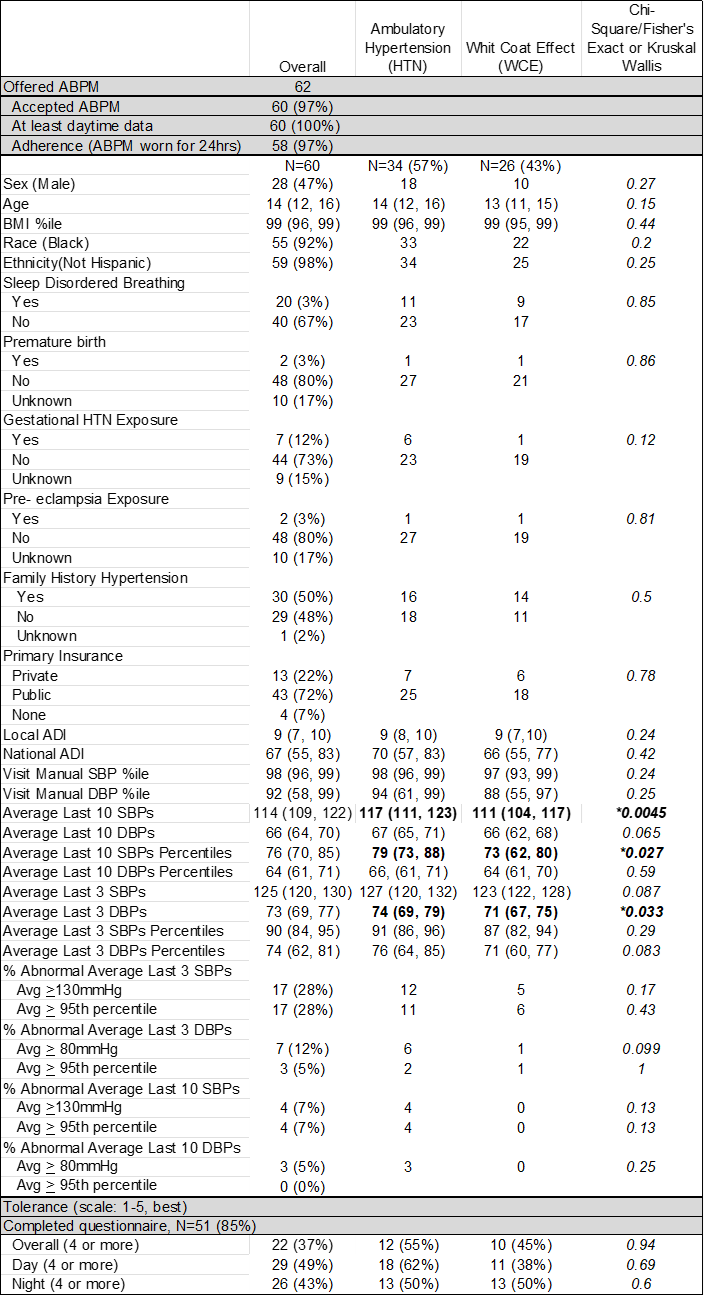

Results: Of the 62 patients offered point-of-care ABPM between 6/30/2023 and 10/2/2024, 60 (97%) accepted ABPM. Of the 60, N=26 (43%) had WCE and 34 (57%) had HTN. Of those with HTN, N=30 out of 33, 91% had nocturnal HTN (1 with missing nighttime BP). Three had isolated daytime HTN. Daytime and nighttime tolerance were scored as high by 57% and 51% of youth, respectively (Table 1). Tolerance of ABPM at night was not significantly different between those with nocturnal HTN vs those without (p=0.31). The average of the last 3 in-office SBPs did not correlate with ABPM results, while the average of the previous 10 in-office SBPs correlated well (p=0.03). Only the last 3 in-office DBPS correlated with ABPM diagnosis of HTN. Overall, stakeholders found “point of care” ABPM to be convenient, easy, more accurate, and tolerated, and they were more likely to accept a diagnosis of HTN based upon the ABPM (Table 2).

Conclusion(s): ABPM placement in the primary care setting is feasible and generally well tolerated. Further studies examining the expanded use of ABPM monitoring within the primary care setting should be considered.

Demographic and ABPM Tolerance Data for Adolescents with Ambulatory Hypertension and White Coat Effect

Tolerance of ABPM was assessed according to a Likert scale (1 to 5, 5=well tolerated).

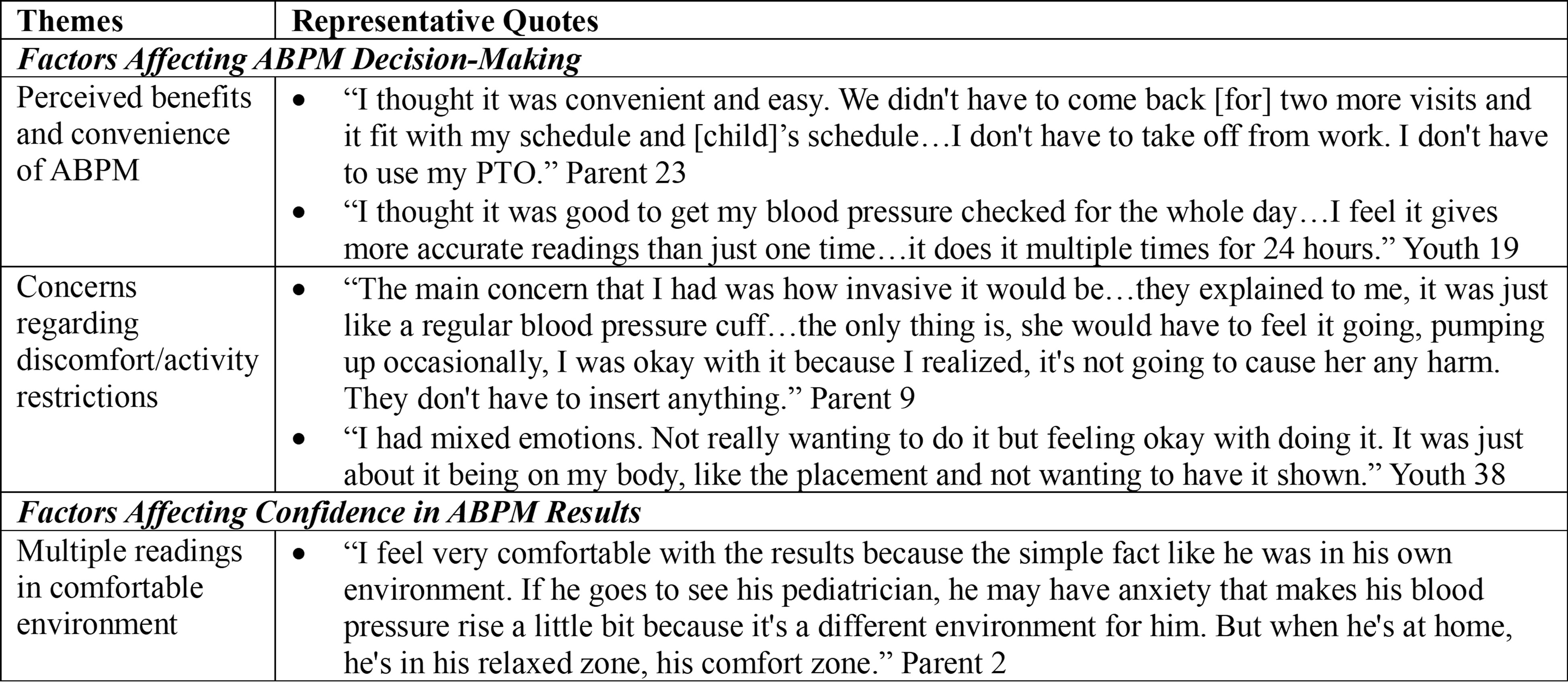

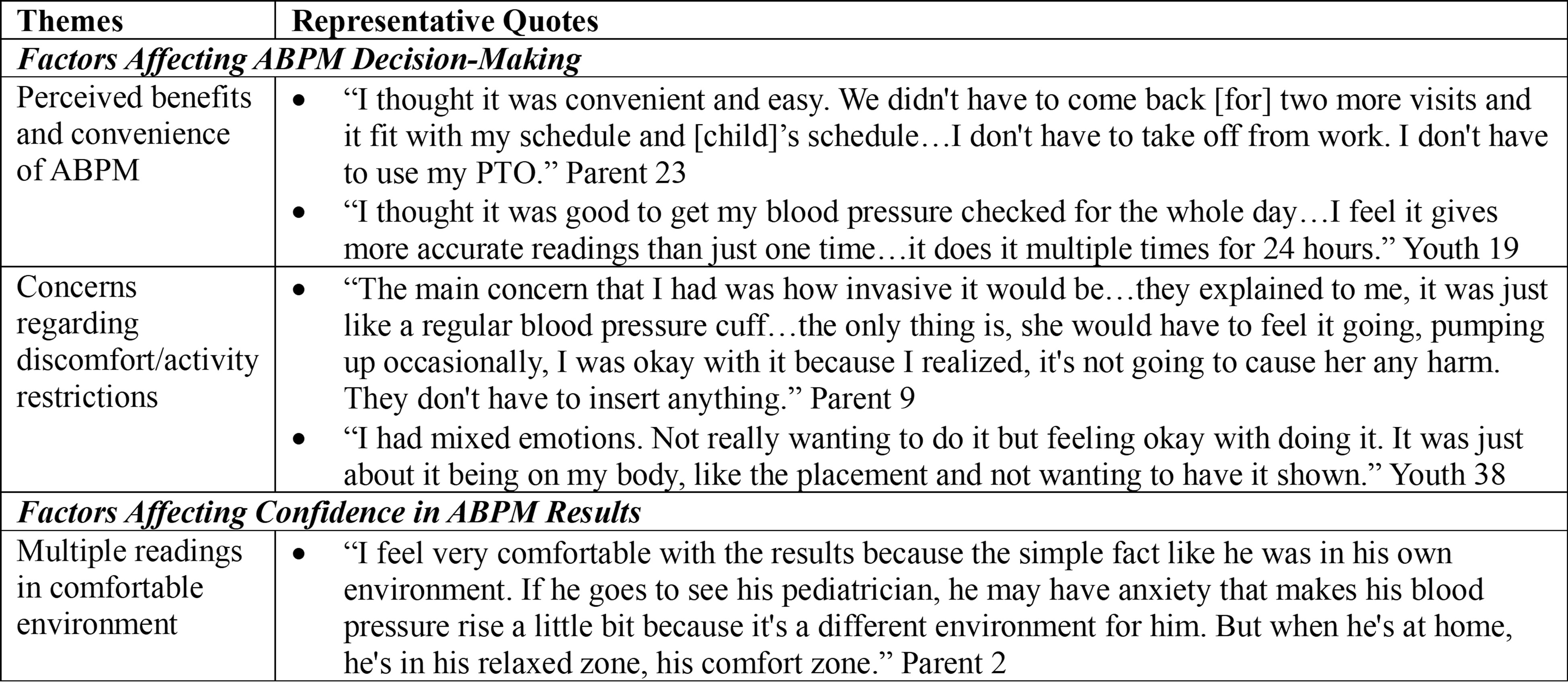

Tolerance of ABPM was assessed according to a Likert scale (1 to 5, 5=well tolerated).Adolescent and Parent Stakeholder Feedback Regarding "Point-of-Care" Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring

Demographic and ABPM Tolerance Data for Adolescents with Ambulatory Hypertension and White Coat Effect

Tolerance of ABPM was assessed according to a Likert scale (1 to 5, 5=well tolerated).

Tolerance of ABPM was assessed according to a Likert scale (1 to 5, 5=well tolerated).Adolescent and Parent Stakeholder Feedback Regarding "Point-of-Care" Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring