Health Equity/Social Determinants of Health 3

Session: Health Equity/Social Determinants of Health 3

429 - Hospital reporting practices and frequency of missing newborn race and ethnicity data

Saturday, April 26, 2025

2:30pm - 4:45pm HST

Publication Number: 429.5182

Leela Sarathy, Mass General for Children, Boston, MA, United States; Ellen K. Kerns, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, United States; Pearl Chang, Seattle Children's Hospital / University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States; Katherine M. Satrom, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States; Sloane E. Magee, The American Academy of Pediatrics, Itasca, IL, United States; Russell McCulloh, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, United States

Leela Sarathy, MD, MSEd (she/her/hers)

Assistant Professor

Mass General for Children

Boston, Massachusetts, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Collection of accurate race and ethnicity data is critical to assessing and improving health equity, and recent literature recommends explicit inclusion of equity outcomes in quality improvement initiatives in order to reduce health disparities. However, documentation of pediatric race and ethnicity, especially in newborn settings, is variable and often inaccurate.

Objective: This study seeks to characterize newborn race/ethnicity reporting practices in a large, multisite national quality improvement (QI) initiative.

Design/Methods: A QI initiative, Learning and Implementing Guidelines for Hyperbilirubinemia Treatment (LIGHT), took place between February 2022 and January 2024. Inpatient phototherapy encounters during birth hospitalization or readmission for newborns

Results: A total of 146 hospitals enrolled and entered data, resulting in 33801 total encounters. Overall, 15% (15% of birth encounters and 13% of readmission encounters) were missing information on newborn race and ethnicity (Tables 1-2). 129 hospitals (88.4%) responded to the post project survey. Of those, only 48% reported using self-reporting methods to document race and ethnicity, while 24% default to maternal race and ethnicity. Although all differences were statistically significant, there were few meaningful differences across hospital characteristics or in birth hospitalizations vs. readmissions. Birth-only hospitals and hospitals with fewer than 1000 yearly deliveries had the lowest missingness rates, while rates were highest in the Northeast and in hospitals defaulting newborn race/ethnicity to “unknown.”

Conclusion(s): Our study noted a significant rate of missing newborn race and ethnicity information, which was relatively consistent across hospital characteristics. A substantial percentage of sites also report defaulting to maternal race and ethnicity, risking additional inaccuracies in reporting. These findings suggest the problem of missingness is pervasive across the US healthcare system. Next steps include a more comprehensive survey to assess the presence of these issues at hospitals beyond the LIGHT collaborative and to better understand best practices. System-wide solutions are essential to improving availability and accuracy of this demographic information and ultimately improving health equity in the newborn setting.

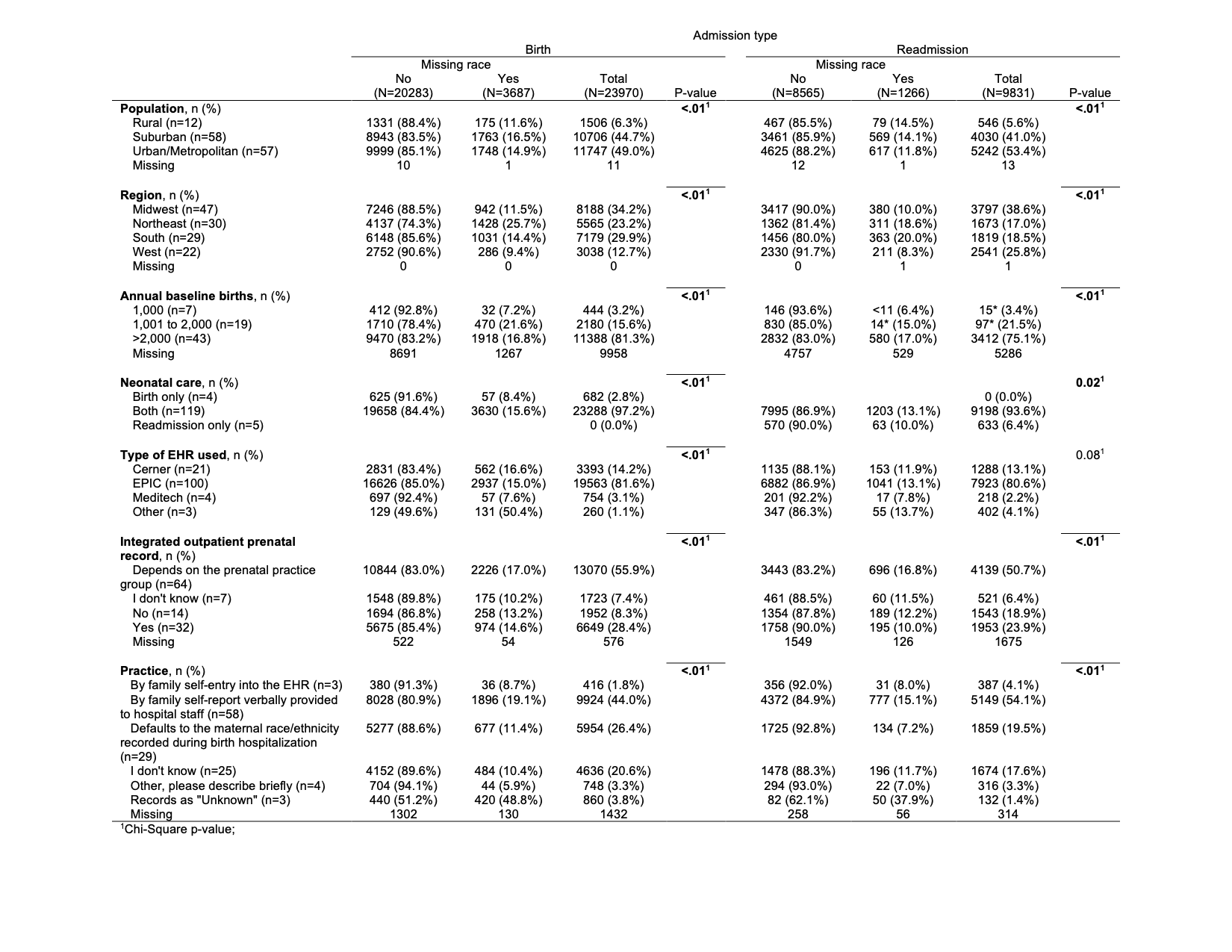

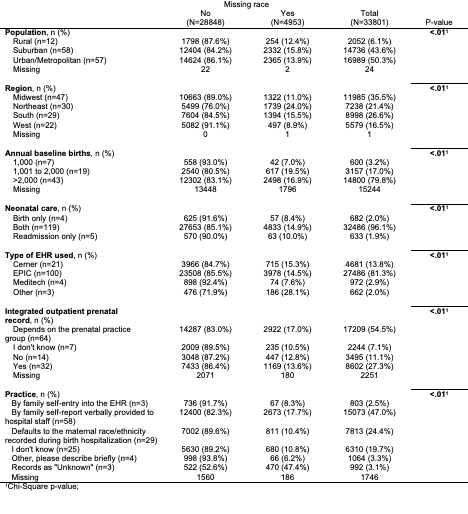

Table 1: Associations between race missingness and hospital characteristics

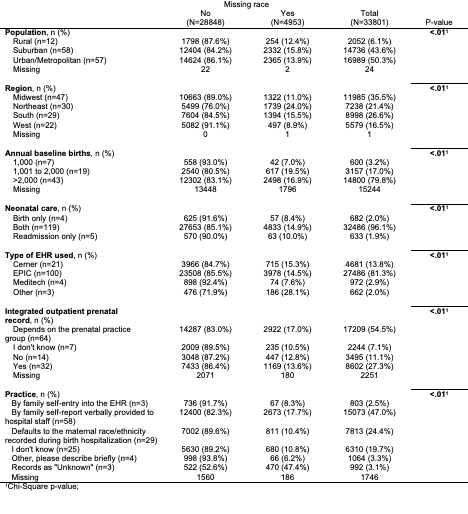

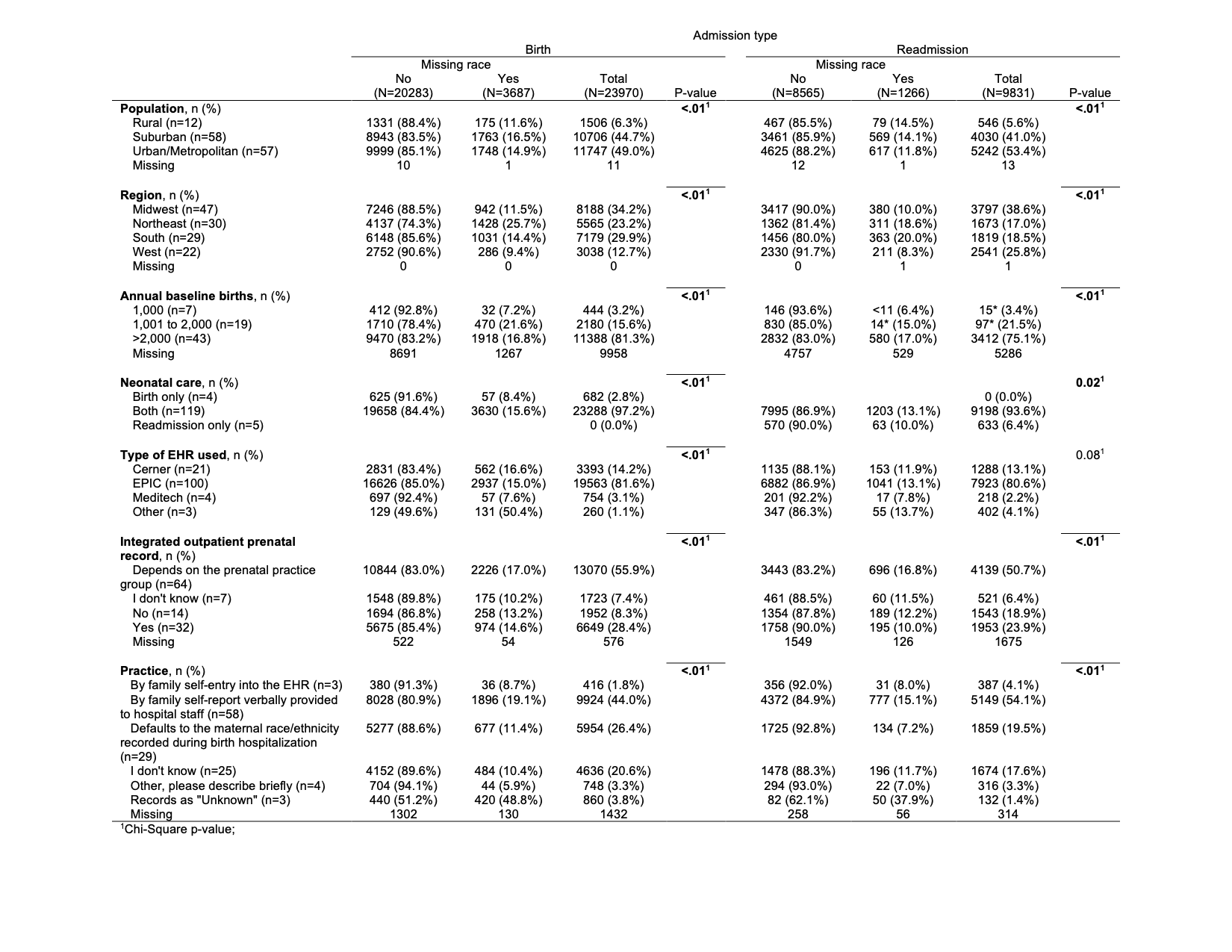

Table 2: Associations between race missingness and hospital characteristics stratified by admission type

Table 1: Associations between race missingness and hospital characteristics

Table 2: Associations between race missingness and hospital characteristics stratified by admission type