Adolescent Medicine 3: E-Cigarettes & Other Substances

Session: Adolescent Medicine 3: E-Cigarettes & Other Substances

116 - Smoking During Pregnancy Does Not Increase the Adolescent Health Risks Associated with Maternal Pre-Pregnancy Body Mass Index

Monday, April 28, 2025

7:00am - 9:15am HST

Publication Number: 116.6933

Sumera Aziz, University of Alberta Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, Edmonton, AB, Canada; sarka Lisonkova, UBC, Vancouver, BC, Canada; YE SHEN, BC Children's Hospital Research Institute, Richmond, BC, Canada; Jeffrey N.. Bone, BC Children's Hosiptal Research Institute, Vancouver, BC, Canada; Lindsay Richter, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada; Joseph Ting, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada

.jpg)

Joseph Yuk Ting, MD, MPH

Associate Professor

University of Alberta

Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and smoking during pregnancy are known to influence adolescent health outcomes, yet their combined effect is not well understood.

Objective: To explore whether smoking during pregnancy modifies the relationship between maternal BMI and adolescent health.

Design/Methods: We undertook a retrospective population-based cohort study of adolescents 10-17 years), born between 2004-2012, using data from Population Data BC (PopData BC) including British Columbia Perinatal Data Registry and administrative health registries, and vital statistics deaths. BMI and smoking during pregnancy were self-reported. We classified women into underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m²), normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m²), overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m²), and obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m²). Poisson regression was used to estimate adjusted risk ratios (ARRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), between BMI and adolescent health outcomes, including hospitalizations, emergency (ER) visits, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, physician consultations, and adolescent morbidity.

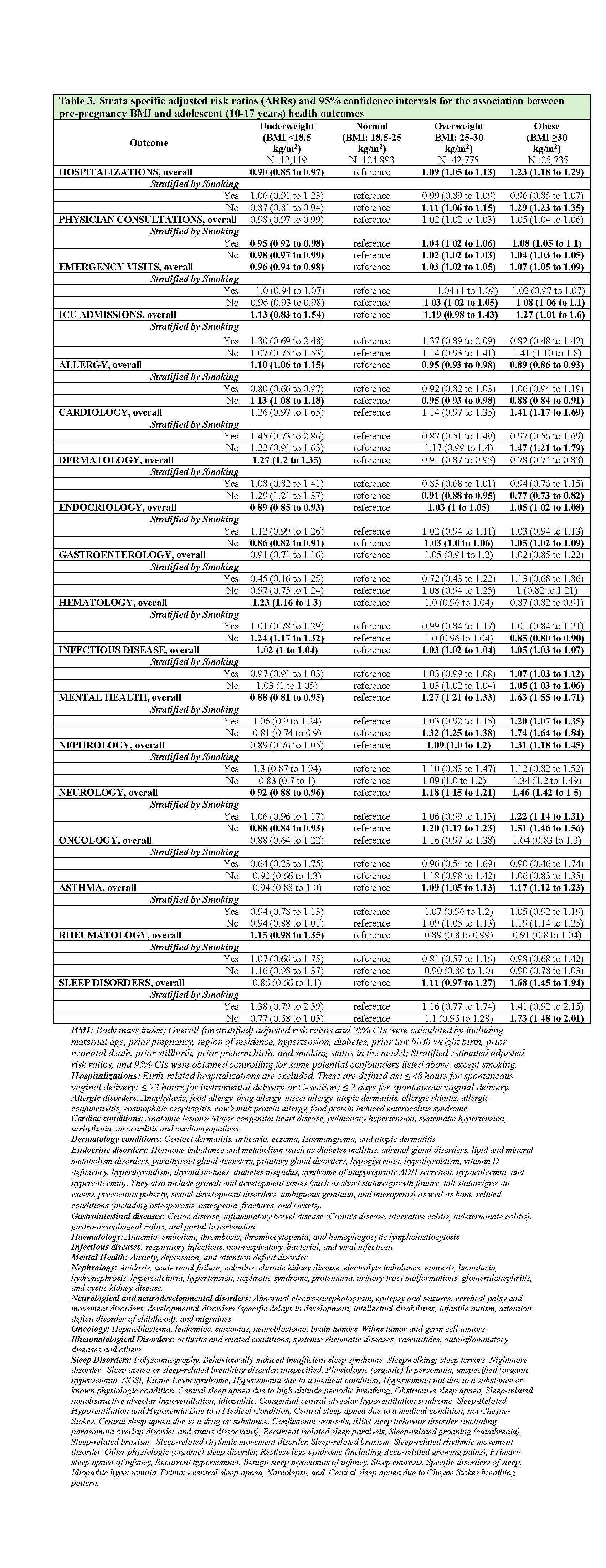

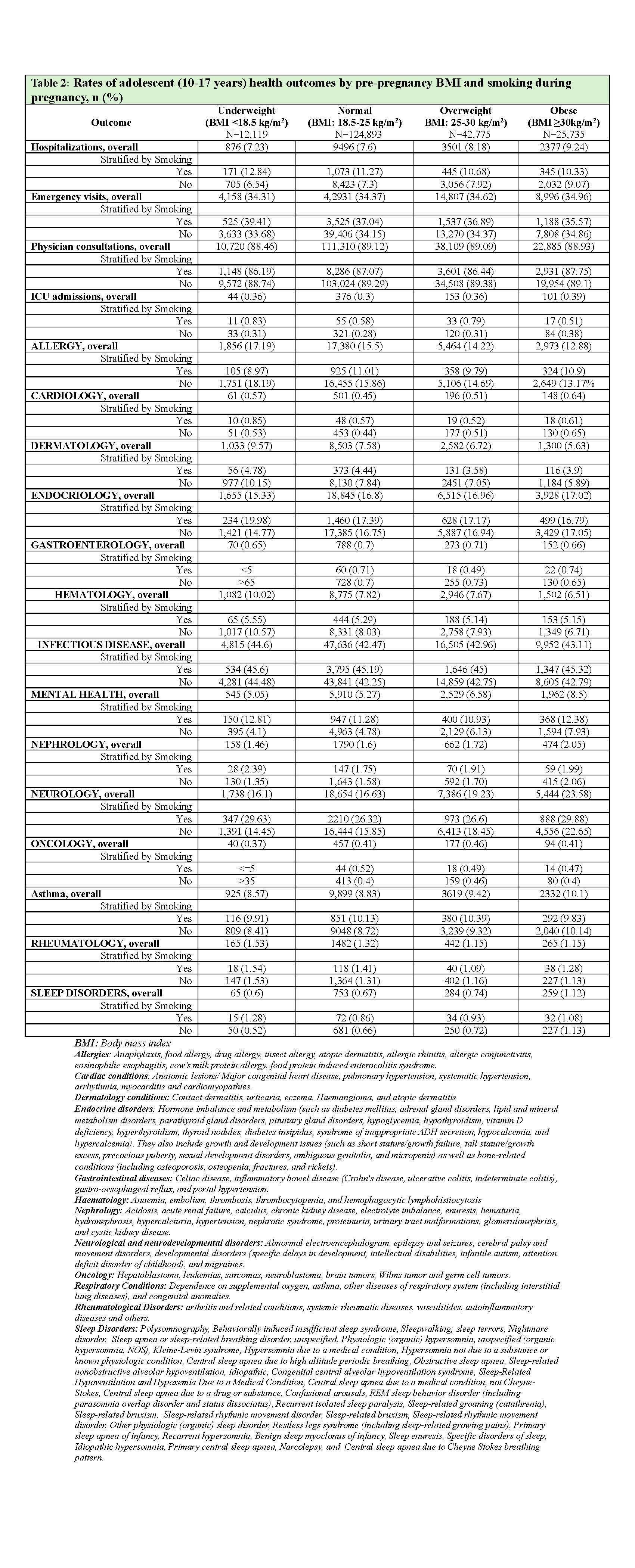

Results: In the cohort of 205,522 adolescents, 6% of mothers were underweight, 61% had normal BMI, 21% overweight, and 13% obese; 8.93% mothers were smokers during pregnancy (Table 1). Health care utilization rates in adolescents ranged between < 1% for ICU admissions to approximately 90% for physician consultations, whereas adolescent morbidity rates varied between < 1% each for oncology, gastrointestinal, and cardiac disorders to about 45% for infections, across maternal pre-pregnancy BMI categories (Table 2). Compared with mothers with normal BMI, the risk of hospitalizations, ER visits, physician consultations, asthma, infections, endocrinology, nephrology, neurology and neurodevelopmental, mental health, and sleep disorders increased with increasing maternal BMI. Offspring of underweight vs. women with normal BMI were more likely to develop allergies (ARR: 1.10; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.15), dermatology (ARR: 1.27; 95% CI: 1.20, 1.35), and hematology (ARR: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.16, 1.30) disorders (Table 3).

Conclusion(s): Higher pre-pregnancy BMI increased the risk of most adolescent health outcomes and associated health care utilization, while underweight mothers had offspring with higher risks of allergies, hematological, and skin conditions. Smoking during pregnancy did not increase the risk for these outcomes. The findings highlight distinct adolescent health risks associated with both high and low maternal BMI, underscoring the need for tailored health interventions across BMI ranges.

CV_Sumera_Aziz.pdf

Rates of adolescent (10-17 years) health outcomes by pre-pregnancy BMI and smoking during pregnancy, n (%)

Strata specific adjusted risk ratios (ARRs) and 95% confidence intervals for the association between pre-pregnancy BMI and adolescent (10-17 years) health outcomes.