Global Neonatal & Children's Health 4

Session: Global Neonatal & Children's Health 4

778 - Palliative Care Communication in a High-Volume Tertiary Referral Hospital Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in Ethiopia

Sunday, April 27, 2025

8:30am - 10:45am HST

Publication Number: 778.5608

Sahar T. Rahiem, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, United States; Miraj F. Alemar, St. Paul's Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Adis Abeba, Ethiopia; Redeat Workneh, St Paul's Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Adis Abeba, Ethiopia; Sharla Rent, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, United States; Krystle M.. Perez, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States; Stephanie K.. Kukora, Children's Research Institute, Children's Mercy Hospital, Children's Mercy, Kansas City, MO, United States; Gregory C.. Valentine, University of Washington School of Medicine, Tacoma, WA, United States; Mahlet Abayneh, St Paul's Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis ABABA, Adis Abeba, Ethiopia

Sahar T. Rahiem, MD, MHS (she/her/hers)

Perinatal-Neonatal Fellow

University of Washington School of Medicine

Seattle, Washington, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Palliative care communication needs are not well studied in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), despite having the highest burden of neonatal morbidity and mortality. It is unclear how palliative care principles and practices, developed for high-resource neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), may be adapted to low-resource settings in a way that is appropriate for patients and practical for providers.

Objective: To evaluate current practices and barriers related to palliative care among healthcare providers in the NICU of St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College (SPHMMC) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Design/Methods: We investigated the palliative care needs and practices of providers in the SPHMMC NICU via a quantitative survey, including the nature of provider communication with patient families and the approach to counseling, decision-making, and end-of-life care. The survey was developed through collaboration with research experts in global neonatal palliative care and local clinicians at SPHMMC. Pre-testing with local providers ensured survey clarity and reliability before the finalized survey was self-administered to SPHMMC NICU providers. Data was collected anonymously from July to September 2024. Results were analyzed using simple descriptive statistics.

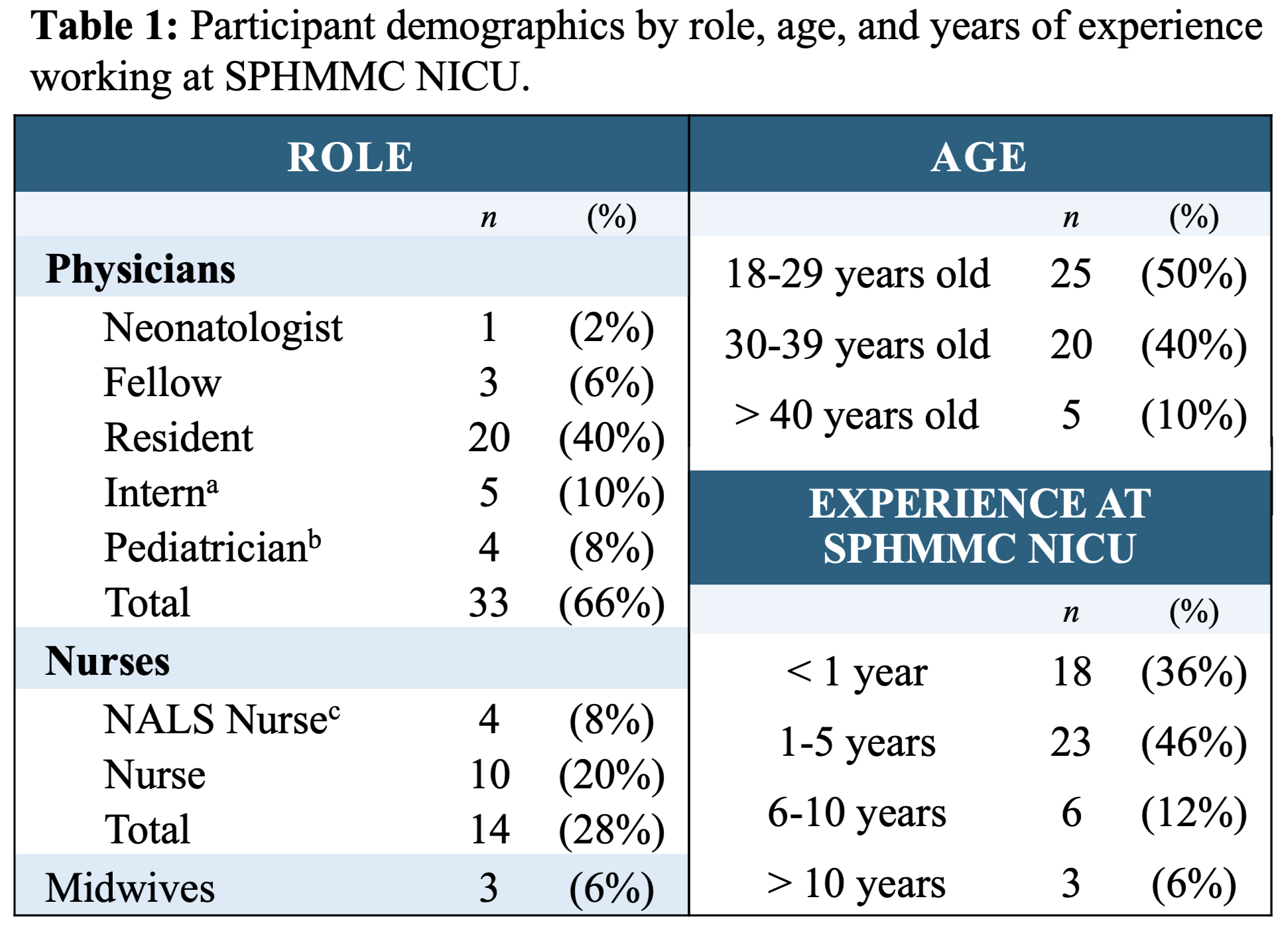

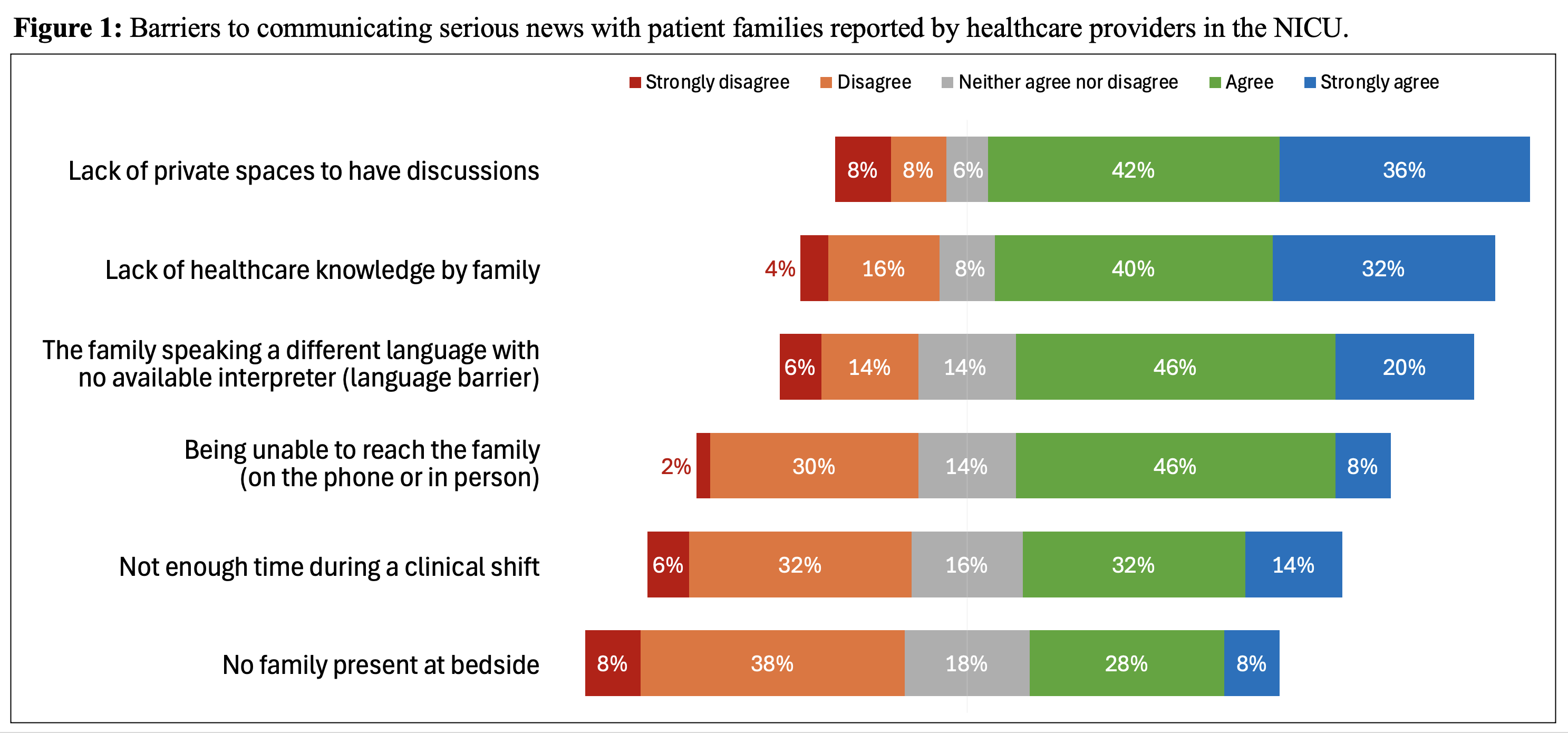

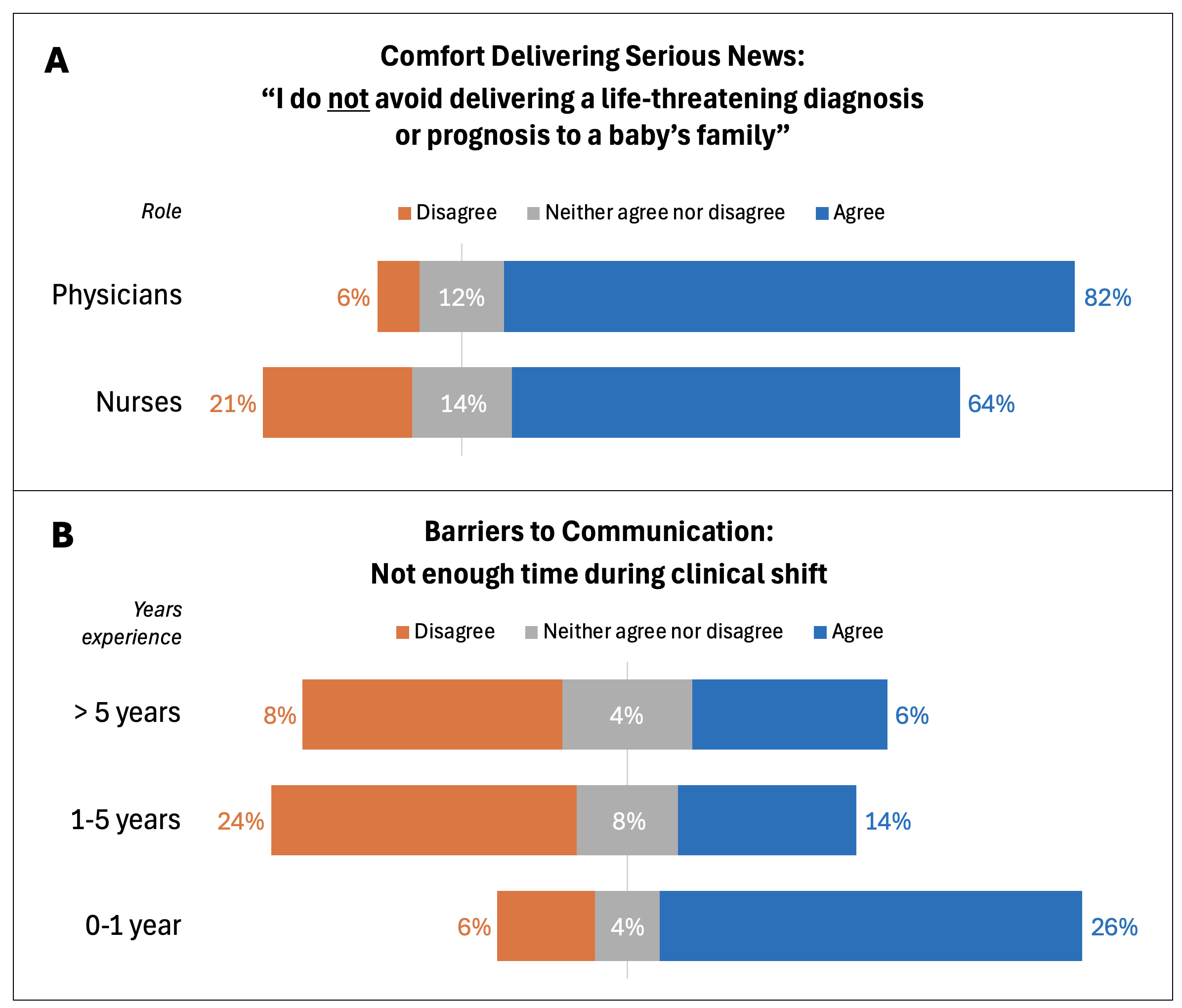

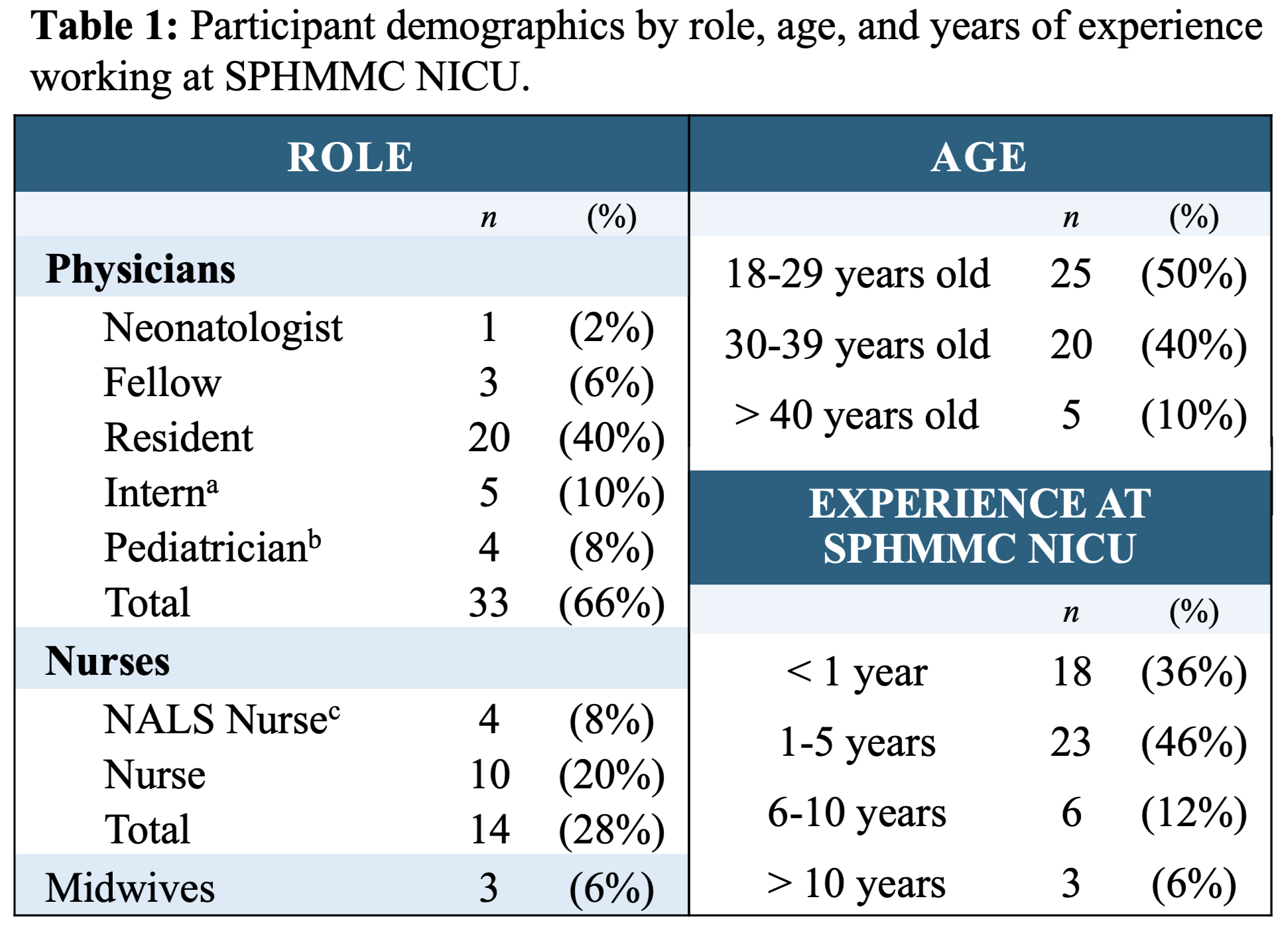

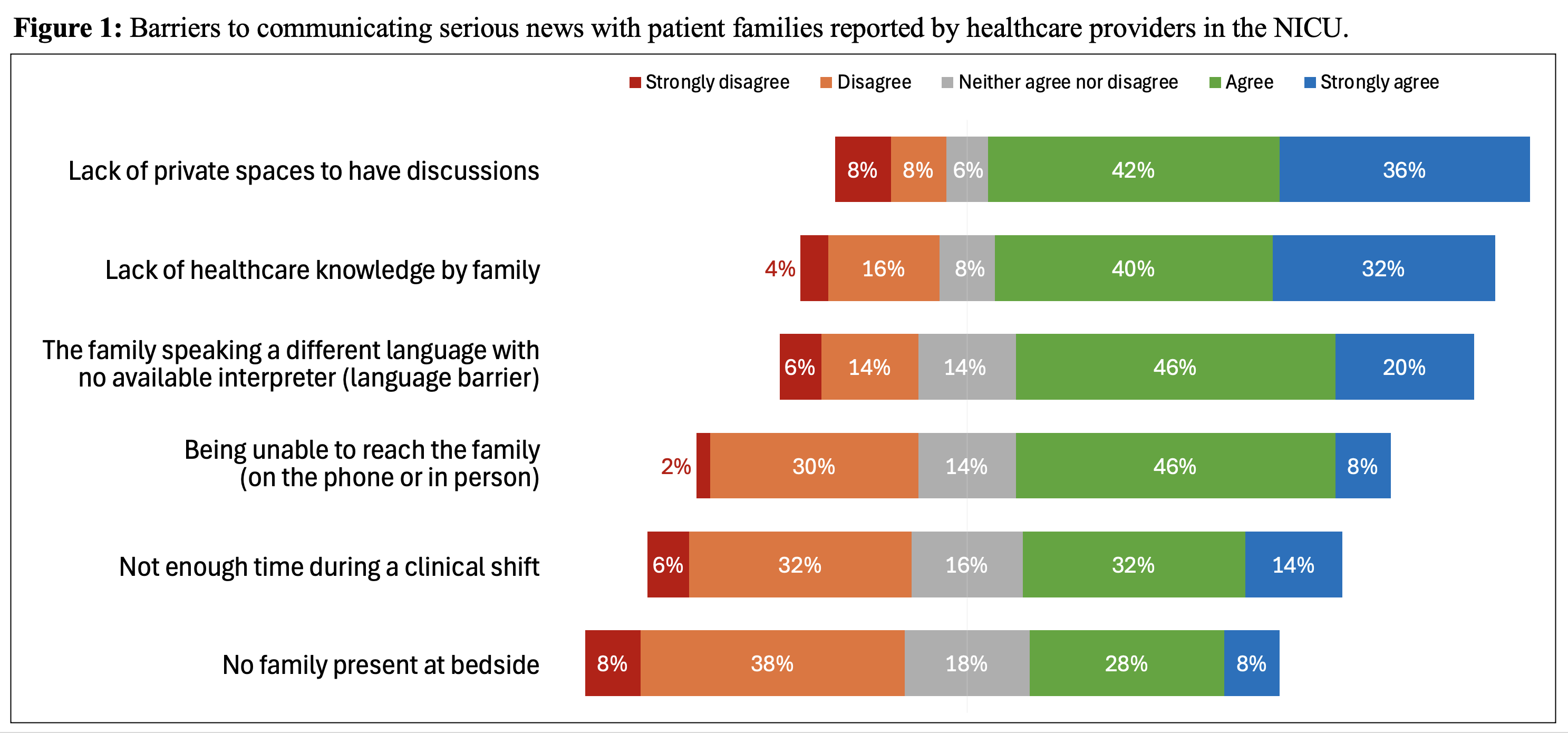

Results: The survey had a 96% response rate (n=50 of 52). Participant demographics are summarized in Table 1. Providers reported agreement (“agree” or “strongly agree”) that leading barriers to communicating serious news with patient families are: lack of private spaces (78%), low health literacy of families (72%), and language barriers (66%). See Figures 1 & 2. Certain maternal social factors were “likely” or “extremely likely” to influence their counseling and medical recommendations, including available family support (98%), residential locality (90%), marital status (84%), and household size (70%). While all providers ascribed the responsibility of discussing serious news to the physician, only 39% of surveyed physicians reported comfort doing so. Nearly all participants (98%) acknowledge the importance of specialized communication training in discussions with families.

Conclusion(s): Healthcare providers in the SPHMMC NICU recognize the importance of communication with patient families, while identifying the barriers and discomfort in doing so effectively. The existing approaches to palliative care communication used in high-resource settings should be culturally and contextually adapted to the barriers inherent in LMICs to adequately address our emerging understanding of the systemic challenges faced by providers in a low-resource NICU.

Table 1: Participant demographics by role, age, and years of experience working at SPHMMC NICU.

a An intern is in their final year of medical school and considered a physician in Ethiopia.

a An intern is in their final year of medical school and considered a physician in Ethiopia.b A pediatrician is a physician who has completed pediatrics residency.

c NALS Nurse = Neonatal Advanced Life Support Nurse. A nurse certified in neonatal resuscitation.

Figure 1: Barriers to communicating serious news with patient families reported by healthcare providers in the NICU.

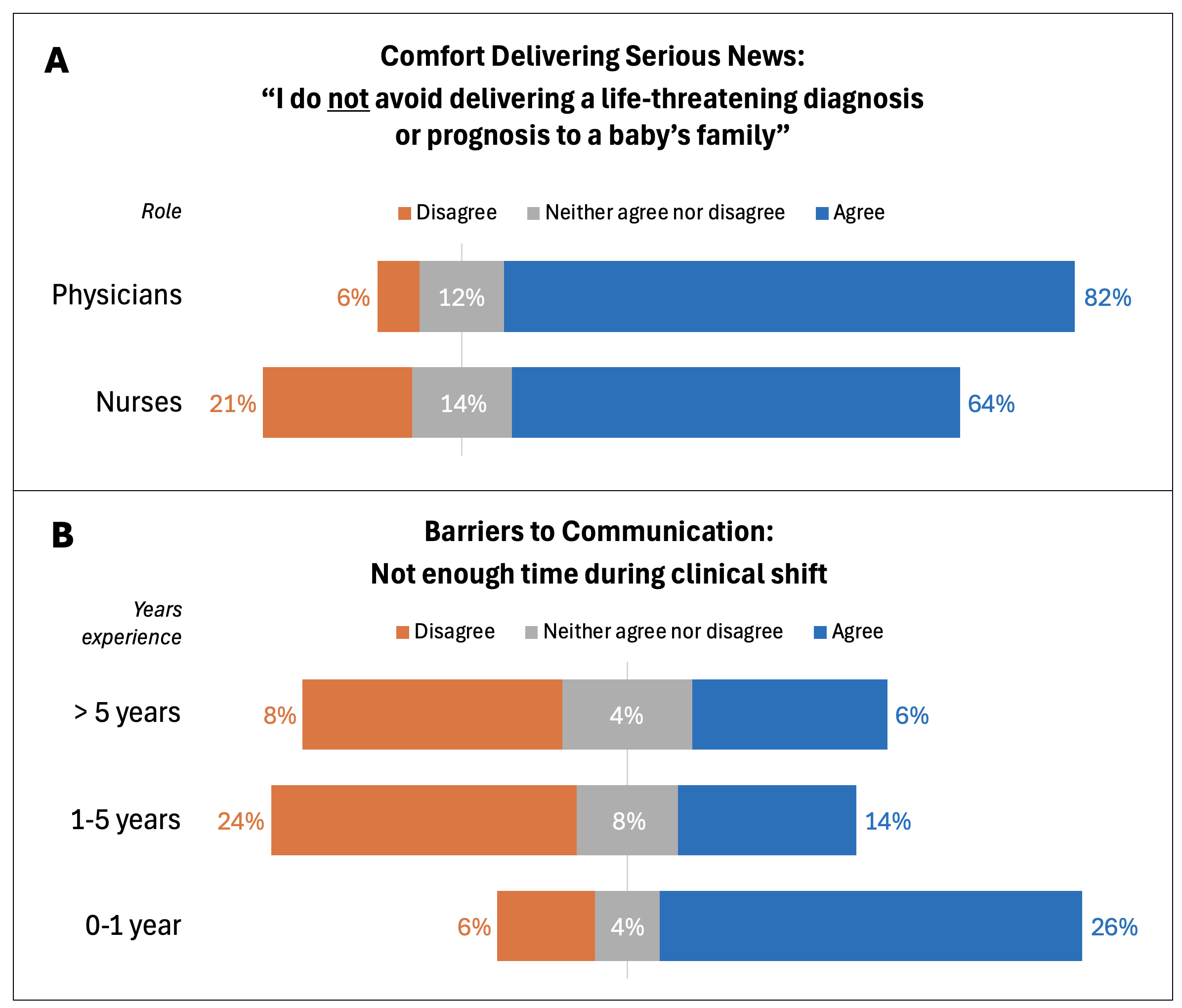

Figure 2A: Comfort Delivering Serious News. Figure 2B: Barriers to Communication: Not enough time during clinical shift.

2A: Physicians in the NICU report less avoidance delivering serious news to patient families than nurses. 2B: “Not enough time during a clinical shift” as a barrier to communication with patient families correlated to years of work experience. Healthcare providers with more than 5 years of experience do not report having enough time during their clinical shift as a barrier to communicating with patient families as much as providers with fewer years experience.

2A: Physicians in the NICU report less avoidance delivering serious news to patient families than nurses. 2B: “Not enough time during a clinical shift” as a barrier to communication with patient families correlated to years of work experience. Healthcare providers with more than 5 years of experience do not report having enough time during their clinical shift as a barrier to communicating with patient families as much as providers with fewer years experience.Table 1: Participant demographics by role, age, and years of experience working at SPHMMC NICU.

a An intern is in their final year of medical school and considered a physician in Ethiopia.

a An intern is in their final year of medical school and considered a physician in Ethiopia.b A pediatrician is a physician who has completed pediatrics residency.

c NALS Nurse = Neonatal Advanced Life Support Nurse. A nurse certified in neonatal resuscitation.

Figure 1: Barriers to communicating serious news with patient families reported by healthcare providers in the NICU.

Figure 2A: Comfort Delivering Serious News. Figure 2B: Barriers to Communication: Not enough time during clinical shift.

2A: Physicians in the NICU report less avoidance delivering serious news to patient families than nurses. 2B: “Not enough time during a clinical shift” as a barrier to communication with patient families correlated to years of work experience. Healthcare providers with more than 5 years of experience do not report having enough time during their clinical shift as a barrier to communicating with patient families as much as providers with fewer years experience.

2A: Physicians in the NICU report less avoidance delivering serious news to patient families than nurses. 2B: “Not enough time during a clinical shift” as a barrier to communication with patient families correlated to years of work experience. Healthcare providers with more than 5 years of experience do not report having enough time during their clinical shift as a barrier to communicating with patient families as much as providers with fewer years experience.